Mobile money usage is considered a cheap, accessible, secure, and convenient alternative to traditional banking. In Uganda, over 34 million people have registered for mobile money accounts, and there is an annual transaction value of over $20 billion. The number of people with mobile money accounts in the country has increased annually since its inception in 2009. However, the legal framework regulating mobile money usage and policies has become unfavourable for Ugandans, causing a decrease in usage.

The Excise Duty (Amendment) Act 2018 provides for a 1 percent tax on the value of the mobile money transaction. But amidst an outcry from Ugandans, the tax was revised to 0.5 percent. Despite the reduction, the tax remains regressive and unequal, hindering Uganda’s move towards a cashless economy. The tax imposes an additional burden on individuals’ income and profits, discouraging them from using mobile money services. Users now have to consider other options for banking before opting for mobile money. The tax is also a form of double, and in some cases, triple, or even quadruple, taxation, as the money being subjected to the 0.5 percent tax is already taxed through an employer or business. At the very core of it, the 0.5 percent tax violates the taxation principles of fairness and neutrality as individuals are prompted to change their behavioural patterns. As Ugandans find ways to evade the unfair taxation policy, mobile money services suffer a drop in demand.

Research has shown that the burden of the 0.5 percent mobile money tax falls unjustifiably on the poor. Data from the Central Bank of Uganda and Uganda Revenue Authority reveals that the average mobile money transaction value has dropped by over 40 percent after the introduction of the tax, indicating higher value transactions have migrated to cash and/or agent banking, where withdrawals are not taxed. Similarly, there is a strong correlation between income levels and migration to agent banking as a direct result of the tax. The introduction of the tax has led wealthier and more urban users to switch to agent banking as a mitigation mechanism, while people with lower incomes are far less likely to have switched to agent banking as a direct result of the tax. Given that 41 percent of Ugandans live below the poverty line, the tax is an unwelcome strain on their financial stability.

Furthermore, the burden of the tax on mobile money withdrawals is felt disproportionately by those living in rural areas. In 2012, the World Bank found that mobile money could be particularly useful for connecting rural areas in Africa to basic financial services since most households in such areas are without a bank account. Estimates indicate that over 9 million Ugandans need to travel more than an hour to access a bank branch. Unfortunately, the imposition of the tax has once again left these communities without inclusive means of accessing commercial banking services.

Additionally, the sending and/or withdrawal charges impose a heavy burden on users. Mobile money transactions have become rather expensive, impacting negatively on the formalisation of the Ugandan economy. The added cost of these transactions has become unsustainable for the average person. A report by the UN Capital Development Fund indicates that hundreds of thousands of payments in several agriculture value chains, which were in the process of being digitised, have had to be discontinued as a direct result of the tax. Consequently, payments in the agricultural sector have mostly reverted to cash.

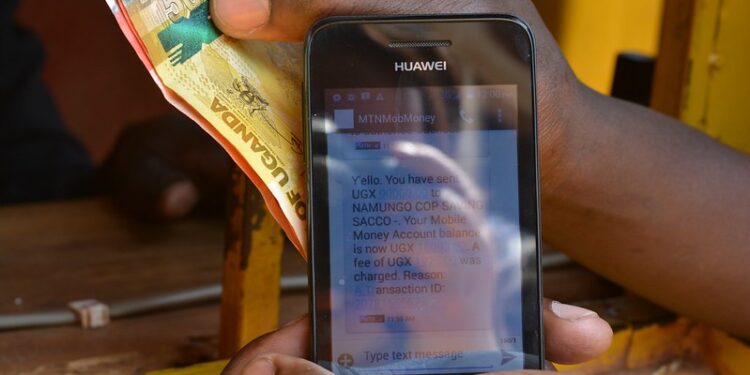

The mobile money system is designed in such a way that users are trapped in a costly cycle of consumption. While depositing funds into a mobile money account is free, withdrawals and transfers are taxed and levied by both the government and service providers. These excessive fees are applied to every single mobile money transaction, making the entire system unnecessarily expensive. Furthermore, the billing system used by mobile money only adds to user confusion. The transaction fees and a 0.5% tax are displayed together in the USSD code received after a transaction. This unclear billing method is unfair, particularly to the illiterate population in Uganda. Tax codes should be simple for taxpayers to understand and for governments to enforce. However, the complexities surrounding mobile money charges are making it difficult for users to make informed decisions and are dissuading them from using the service altogether.

A surge of fraud and misrepresentation in mobile money transactions is creating a climate of uncertainty. Although the National Payment Systems Act of 2020 caters to the safety and efficiency of payment systems, digital hoaxes still run rampant, making them unsafe. Approximately 3 out of every 5 people have encountered fraud attempts or have been defrauded at least once, placing the estimate at about 60 percent fraud attempts. It is of note that the statistics are not inclusive, as complainants often choose not to report. Mobile money transactions have become the playground for fraudsters, hackers, and scammers. In the 2020 Pegasus Technologies hacking scandal, hackers used 2,000 mobile SIM cards to gain access to the mobile money payment system, stealing more than $3.2 million. The Uganda Police Annual Crime and Road Safety Report of 2019 shows that 41 billion Ugandan shillings ($11 million) was lost to criminals through cybercrimes in that year alone. As a result, monetary safety is a major concern for users before engaging with mobile money services.

With the expansion of agent banking services, mobile money is losing its position as a cheap and secure alternative. The operationalization of the Financial Institutions (Amendment) Act 2016 and the Financial Institutions (Agent Banking) Regulations, 2017, introduced agency banking in Uganda. Reliance on bank branches and automated teller machines (ATM) as main service access points decreases daily. The extension of services traditionally offered in bank branches has expanded banks’ presence, particularly in rural areas. In the months following the implementation of the tax, the total value of Mobile Money transactions fell by around UGX 1 trillion, while the monthly value of agent banking transactions increased by 171 percent. As of 2021, Agency Banking boasts over 1 million monthly customer transactions totaling $250,000 per month. Greater access to and increased convenience of formal financial services are rendering mobile money redundant.

While mobile money has the potential to be a valuable tool for financial inclusion, the legal framework and policies surrounding it have become unfavourable for Ugandans. It is imperative that all relevant stakeholders work together to address the issues affecting the system and revise it to better serve the needs of Ugandans. Failure to do so may result in the loss of trust and eventual abandonment of these services.

ــــــــــــــــــــ

This article expresses the views and opinions of the author, and does not necessarily reflect the views of Qiraat Africa and its editors.