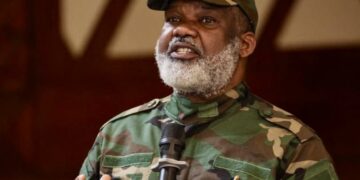

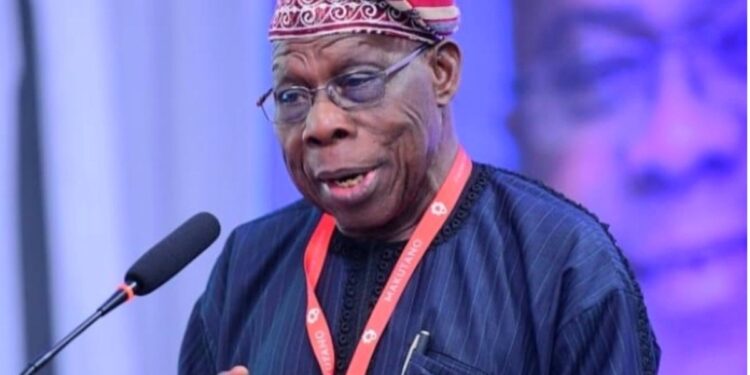

Olusegun Obasanjo is a pivotal political and military figure in modern Nigerian history, having held leadership roles during key periods of the regime and the state. His career was characterized by the interplay of military and civilian power, with significant impact on Nigeria’s democratic transition. Despite achievements in achieving relative stability and development, his tenure was not without challenges and criticism of his performance in the areas of governance, human rights, and comprehensive development, making his assessment a subject of ongoing debate within political and intellectual circles.

Obasanjo led Nigeria twice: first as a military governor from 1976 to 1979, and then as an elected civilian president from 1999 to 2007. He was of the Yoruba ethnic group, born on March 5, 1937, in the village of Ibogun-Ologun, Ifo, Southern Region, British Nigeria (now Ibogun-Olaogun, Ogun State, Nigeria) in Nigeria. He grew up in a simple rural environment in a farming family, where he lived in modest living conditions and was forced to work various odd jobs to support his education. He joined the army in 1958, beginning a military career that later led him to leadership positions during critical periods in Nigeria’s history.

Obasanjo spent his early years in the village of Ibogun-Ologun. He began his education at Baptist schools and later attended secondary schools in Abeokuta, the capital of Ogun State. Despite the economic challenges he faced early in life, he continued his education and worked hard to support himself during his studies.

He joined the Nigerian Army Academy in the late 1950s and developed his engineering and military skills, benefiting from internal and external training that included service in regions such as the Congo, India, and Britain. He rose through the ranks to become a prominent officer and participated in the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), where he played a key role in accepting the surrender of the Biafran forces, an event he approached with responsibility to preserve the country’s unity.

In 1975, Obasanjo participated in the military coup that installed a Supreme Military Council under joint leadership. Following the assassination of General Murtala Muhammed in 1976, Obasanjo was appointed head of state, where he continued to implement policies that included economic austerity and the expansion of free education. He also worked to strengthen relations with the United States and support the anti-apartheid movements in South Africa.

His military rule was characterized by a focus on internal reforms and efforts to return the country to civilian rule. He successfully organized democratic elections in 1979, handing power to a civilian government led by Shehu Shagari, which led him to leave power and return to civilian life and farming in his village.

Obasanjo returned to politics in the late 1990s after years of military rule and political instability in Nigeria. He was a founding member of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), which won the majority in the 1999 elections. He won the presidency of Nigeria in May 1999, the first presidential election after the return of democracy.

During his two terms in office (1999–2007), he addressed significant challenges such as administrative corruption, ensuring political stability, combating poverty, and improving basic infrastructure. He also implemented various reforms, particularly in the areas of the economy and foreign policy, and sought to strengthen Nigeria’s role as a regional and international power.

Obasanjo’s administration was characterized by an attempt to achieve a balance between the country’s various ethnic and religious groups, a difficult task in a multiethnic and multicultural country. A prominent feature of his presidency was the adoption of a policy of economic liberalism, encouraging private investment and implementing structural reforms aimed at reducing the economy’s dependence on oil.

Internationally, he contributed to strengthening Nigeria’s role in Africa and the world, and encouraged peace and dialogue in continental conflicts, particularly in West Africa. He also played a role in supporting the African Union and its initiatives.

Obasanjo faced many challenges during his tenure, including the fight against corruption, which some criticized as not being sufficiently stringent. There was also criticism that social and economic reforms were slow compared to the scale of the challenges facing Nigeria, including high poverty and unemployment rates and the unequal distribution of wealth.

Some of his policies also sparked controversy regarding press freedom and human rights, with his government sometimes accused of suppressing political opposition and activists. Security stability remained fragile in some areas, particularly with the emergence of armed movements and tribal violence.

After his term ended in 2007, Obasanjo continued to play an influential role as a senior African leader and experienced statesman, participating in numerous diplomatic initiatives and international issues, including mediating regional conflicts and working to promote democratic development in Africa.

He retained significant influence in political debates within Nigeria, even though his official tenure in power had ended. He authored several books chronicling his experiences and perspectives on governance, politics, and development.

Olusegun Obasanjo Quotes

The lice of poor performance in government – poverty, insecurity, poor economic management, nepotism, gross dereliction of duty, condonation of misdeed – if not outright encouragement of it, lack of progress and hope for the future, lack of national cohesion and poor management of internal political dynamics and widening inequality – are very much with us today. With such lice of general and specific poor performance and crying poverty with us, our fingers will not be dry of ‘blood’.

“another drawback is inadequate training. Management training on a regular basis is a sine-qua-non for good performance in management. The principles of management are basically the same as they involve men, money and materials. Applications vary slightly depending on the nature of what is being managed, at what level and for what purpose. New ideas, innovations and new practices may emerge from time to time which a manager needs to be conversant with. Otherwise he will be way behind or even obsolete. Training and exposure act as tonic for renewal and reshaping of a manager. There can be no adequate substitute for such training, interaction and exposure until one ceases to be an active manager. To think that once one is in management position, there is no further need for training through formal and informal interaction and exposure is, I believe, the height of folly.”

― My Watch Volume 1: Early Life and Military

For Africa to move forward, Nigeria must be one of the anchor countries, if not the leading anchor country. It means that Nigeria must be good at home to be good outside. No doubt, our situation in the last decade or so had shown that we are not good enough at home; hence we are invariably absent at the table that we should be abroad.

Wherever I go, I hear Nigerians complaining, murmuring in anguish and anger. But our anger should not be like the anger of the cripple. We can collectively save ourselves from the position we find ourselves. It will not come through self-pity, fruitless complaint or protest but through constructive and positive engagement and collective action for the good of our nation and ourselves and our children and their children. We need moral re-armament and engaging togetherness of people of like-mind and goodwill to come solidly together to lift Nigeria up. This is no time for trading blames or embarking on futile argument and neither should we accept untenable excuses for non-performance.