Since the end of the last ice age, the north and sub-Saharan regions of Africa have been separated by the extremely harsh climate of the sparsely populated Sahara, forming an effective barrier interrupted by only the Nile River. The regions are distinct culturally as well as geographically; the dark-skinned peoples south of the Sahara developed in relative isolation from the rest of the world compared to those living north of the Sahara, who were more influenced by Arab culture and Islam. Significantly, Africa is a resource-rich continent. But until recently, exploration efforts and discoveries were modest. Observers say that despite this abundance, sub-Saharan African countries have often struggled to translate resource endowments into sustainable development for citizens.

As the global drive toward cleaner energy intensifies, the demand for transition minerals presents an important opportunity for many African countries to spur economic and social development. Analysts indicate that Africa’s natural wealth could rise substantially in a generation, provided natural resource exploration and development of extractive projects pick up—as they did in East Asia, the Pacific, and the Middle East in recent decades—the low yields on agricultural crops are given a boost, and more land is brought under cultivation. While the population in high- and upper-middle-income economies is aging rapidly, sub-Saharan Africa is home to one of the world’s youngest population structures. While nearly 70% and 42% of the region’s population are under 30 and 15 years old, respectively, Nearly a quarter of the world’s population under the age of 15 resides in sub-Saharan African economies. These dynamic forces show how important sub-Saharan Africa is to the global order.

When analyzing today’s world, one must not forget that while globalization has done much to reduce distances and increase connectivity, differences, sometimes substantial, still remain. Not only in political culture but also in economic models and social norms. Diversity is one of the world’s most enriching qualities, one that defines and challenges us, but also one that must not lead to forced isolation or forceful imposition. Countries such as Iran are using the weakness of the sub-Saharan African states due to numerous challenges at hand to propagate their agenda. Due to the fact that Iran’s infiltration of Africa is the result of intense efforts that aim to lessen the pressure of Western sanctions on Iran, Iran’s influence has been increasing in African countries, especially since signing the nuclear deal with the West on July 14, 2015, and the constant US pressure and imposition of sanctions on countries that supply Iran with fissile materials for its nuclear program. Hence, Iran is moving far from its old zone of influence.

Iran’s global strategy in the region

Iran has sought to show that it is not isolated on the international scene and that it’s not alone in having problems with the United States. Within its own borders, Tehran also wants to promote its image as an influential global power. But this is a propaganda message that the population no longer believes in, especially when it comes to Africa. Indeed, Iranians have seen no return on investment from their leaders’ African policy. Equally, the Iranian regime has prioritized “exporting revolution” to countries with a Muslim population. African countries, with their internal crises and Muslim populations, have been prime targets. The Iranian regime, either directly or through its Hezbollah terrorist proxy group, has expanded its influence across the continent, mainly south of the Sahara. Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) and Hezbollah have established a strong foothold in Africa, and their activities there accelerated in the early 2010s and reached a new height after 2018. Africa has been designated as one of the main targets for Tehran as it looks to expand its influence beyond the Middle East. The presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005–2013) was a turning point in Iran’s engagement on the continent, as Tehran deepened its ties with African countries, particularly sub-Saharan ones.

Similarly, the Iranian government had established ties with radical Muslim student groups on university campuses and had brought several hundred students from Ghana, Mali, Mauritania, Nigeria, and Senegal to Iran for theological training. Furthermore, Tehran maintained at least 18 embassies in sub-Saharan Africa. Iran was seeking to exploit ties with the nearly 100,000 Shia Muslim minority communities that lived in West Africa. Basically, Tehran was now engaged in an effort to rebuild ties with sub-Saharan Africa that had been broken off or suspended after the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Though Iran has also received support from African countries in the United Nations and other regional and international organizations, In history, the Islamic Republic was one of the first countries to resume trade with South Africa following the end of apartheid, and the two countries have enjoyed strong relations ever since. Trade has been an integral element of this relationship, with Iranian officials estimating the value of Iranian foreign direct investment in South Africa in 2018 at roughly $135 billion. Yet, observers have indicated that Iran invested in several African countries, but the results failed to meet expectations. Analysts noted that with the tension between Iran and the West rising, Iran’s economy suffered significantly from the crippling sanctions imposed by the administration of former U.S. President Barack Obama. Thus, in 2013, when Rouhani succeeded Ahmadinejad as president, Iran’s foreign policy shifted gears to focus on dialogue with the West in an effort to end the deadlock over Iran’s nuclear program. This was in keeping with the traditional position of the so-called moderates, who have long portrayed themselves as advocates of de-escalation with the West.

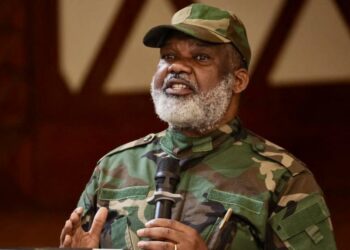

Nevertheless, experts have indicated that in recent years, three centers of power in the Muslim world—Saudi Arabia, Libya, and Iran—have competed for leadership in sub-Saharan Africa. Iran had now replaced Libya as the second-largest source of external support in the region, behind Saudi Arabia. Despite these political gains, the IRI had enjoyed only limited success owing to the hostility of some African governments and the indifference of many African Muslims to Tehran’s revolutionary ideology. Moreover, a contraction in Iranian policy—trying to turn the local Muslim population against both conservative Muslim leaders and some of the governments from which Tehran seeks diplomatic support—undercuts Tehran’s political outreach in the region. Such as the case of prominent Nigerian Shia cleric Sheikh Ibrahim Zakzaky, the leader of the Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN) and the government of the West African nation. Sheikh Zakzaky converted to Shiaism about four decades ago after visiting Iran. Though the Iranian revolution encouraged him to believe that an Islamic revival was also possible in Nigeria, Unfortunately, IMN supporters do not recognize the Nigerian government and see Sheikh Zakzaky as the only legitimate source of authority in the country. They pledge allegiance to Ayatollah Khomeini at their gatherings, and critics have raised concern over the group’s close ties to Iran. A media report noted that Zakzaky and his wife were wounded and arrested following a raid by Nigerian forces at his residence in Zaria, Kaduna State, in 2015. The pair were acquitted of all charges in 2021, after six years of being placed under house arrest. Nigeria’s population is a combination of a predominantly Christian south and a mainly Sunni Muslim north. Shia are estimated at less than 4 million, although there are no official figures.

Sudan lies on the coast of the Red Sea, a key site of competition between global powers, including Iran, as war rages in the Middle East. On April 15, 2023, residents of Khartoum woke up to chaotic scenes as armored vehicles from both forces careered through the streets, with heavy artillery fire ringing throughout the city and fighter jets roaring in the skies above. The two warring parties, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), have continued a longstanding struggle for power. Amplifying tensions are the major geopolitical dimensions at play. Russia, the US, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and, most recently, Iran are among the powers battling for influence in Sudan. Similarly, international media outlets have alleged in early 2024 that Iran has supplied Sudan’s army with combat drones, taking sides in a disastrous civil war fuelled by proxies’ keenness for Red Sea access that has displaced millions and risks destabilizing the wider region. The war has reordered Africa’s third-largest nation with breathtaking speed. It has gutted the capital, Khartoum, which was once a major center of commerce and culture on the Nile. Deserted neighborhoods are now filled with bullet-scarred buildings and bodies buried in shallow graves, according to residents and aid workers.

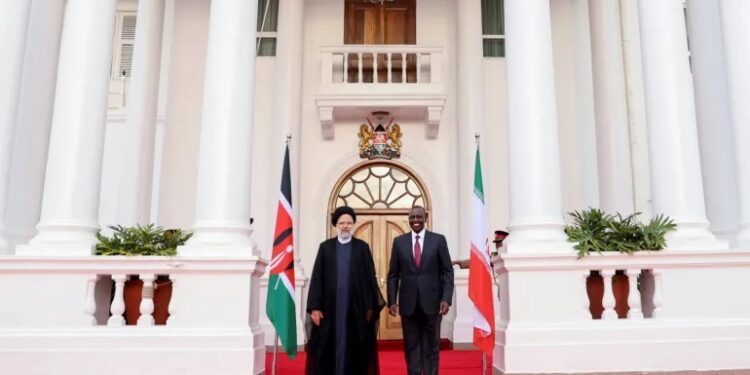

Another country in the region, Mali, provided an opening for Iran and its strategic partner Russia to expand their influence in Africa by distancing themselves from the former colonial power, France. Likewise, Iran also has an interest in Niger. But the country has been under military rule since July, when an elite guard force led by General Abdourahmane Tchiani detained democratically elected President Mohamed Bazoum and declared Tchiani ruler. In late January 2024, Zeine also visited Iran, where he met President Ebrahim Raisi. Iran, meanwhile, has signed several cooperation agreements with Burkina Faso in energy, urban planning, higher education, and construction. Burkina Faso, Mali, and other countries in the Sahel are major repositories of gold, uranium, lithium, manganese, phosphates, limestone, zinc, bauxite, salt, granite, and other valuable natural resources. Deals between Iran and these African governments can potentially provide opportunities for Iranian companies to exploit this natural resource wealth and bypass crippling sanctions. Raisi visited Kenya, Uganda, and Zimbabwe in July. Iran’s trade with Africa has doubled since Raisi came to power in 2021.

Expansion through Shiite movements and International Trade

To conclude, Iran has consistently worked to penetrate Africa by supporting Shiite movements to expand its geopolitical and natural interests. Tehran’s regional foes view Iran’s plans in Africa as a direct threat. Also, Iran views Africa as a potential location to increase connectivity and reduce diplomatic isolation through its key pillars, “Look to the East” and “Third Worldism.” Iran has expanded its influence in many African countries because they share anti-Western and anti-imperialist ideologies. However, Iran will intensify efforts to pivot to non-Western countries, and Africa is likely to be an increasingly important part of this effort. In the minds of officials in Tehran, the expansion of ties with African countries is based on a realistic world view, enabling the Islamic Republic to defend its interests against regional and global enemies.

Still, diplomatic affairs analysts say Iran’s policy toward sub-Saharan Africa turned from maintaining a pro-West status quo under the Shah to disrupting the regional order under the IRI. For geopolitical-strategic reasons, much of the attention of both the Shah and the IRI focused on the Horn of Africa, not surprisingly, given the Horn’s location along the vital Red Sea maritime route and Bab al-Mandab chokepoint. The Shah’s anti-communist containment intervention in the region was welcomed by the United States and other Western countries. Conversely, the Islamist-based ideological policies of the IRI are viewed as disruptive to a pro-Western regional order. They opined that Iran is still far from building an international coalition to create a balance of power with the West. Iran’s inability to achieve its goals results from the active and alert international role of isolating Tehran and preserving the status quo, especially with the latest Saudi efforts to diminish Iran’s presence on the African continent.

ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

This article expresses the views and opinions of the author and does not necessarily reflect the views of Qiraat Africa and its editors.