Robben Island, whose name means “island of sea dogs” or seals in Dutch, is located in Table Bay off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa. It is a flat, oval-shaped piece of land with an area of approximately 5.07 square kilometers. Despite its natural beauty and stunning views of Table Mountain, the island’s international fame stems from its geography and historical role as a tool of isolation, oppression, and persecution.

Robben Island’s use as a prison did not begin with apartheid; rather, its use dates back to the 17th century, specifically to the Dutch (Dutch East India Company) settlement in Cape Town. The island has had various uses throughout history.

From 1658, Dutch colonists began using the island as a site of isolation. Initially, it was used to hold criminal prisoners, as well as political and religious figures from other Dutch colonies, such as the East Indies. The island’s geographical isolation served two purposes: to ensure protection against prisoner escapes and to prevent the spread of disease and epidemics to the mainland. Among the prominent religious figures exiled to the island was Imam Moturu, one of the first imams in Cape Town, who died there in 1754. His shrine today is one of the oldest Islamic monuments in South Africa.

During intermittent periods in the 18th and 19th centuries, the island was used as a hospital for infectious and chronic diseases, particularly a leper colony, and for the mentally ill. This use reinforced the island’s role as a “human waste dump,” where people deemed socially undesirable or a health threat were removed from mainland society. Isolation remained the primary goal, with inadequate healthcare often being provided.

During the two world wars, Robben Island was fortified as part of Cape Town’s coastal defenses, with artillery, fortifications, and an airstrip being constructed. This military use, which ended after World War II, added another layer to the island’s infrastructure, later inherited by the apartheid regime.

With the rise of the National Party to power in 1948 and the formal implementation of apartheid, Robben Island was transformed into a maximum-security prison, primarily for African political prisoners who resisted the regime. Between 1961 and its closure as a political prison in 1991, the island held approximately 3,000 political prisoners.

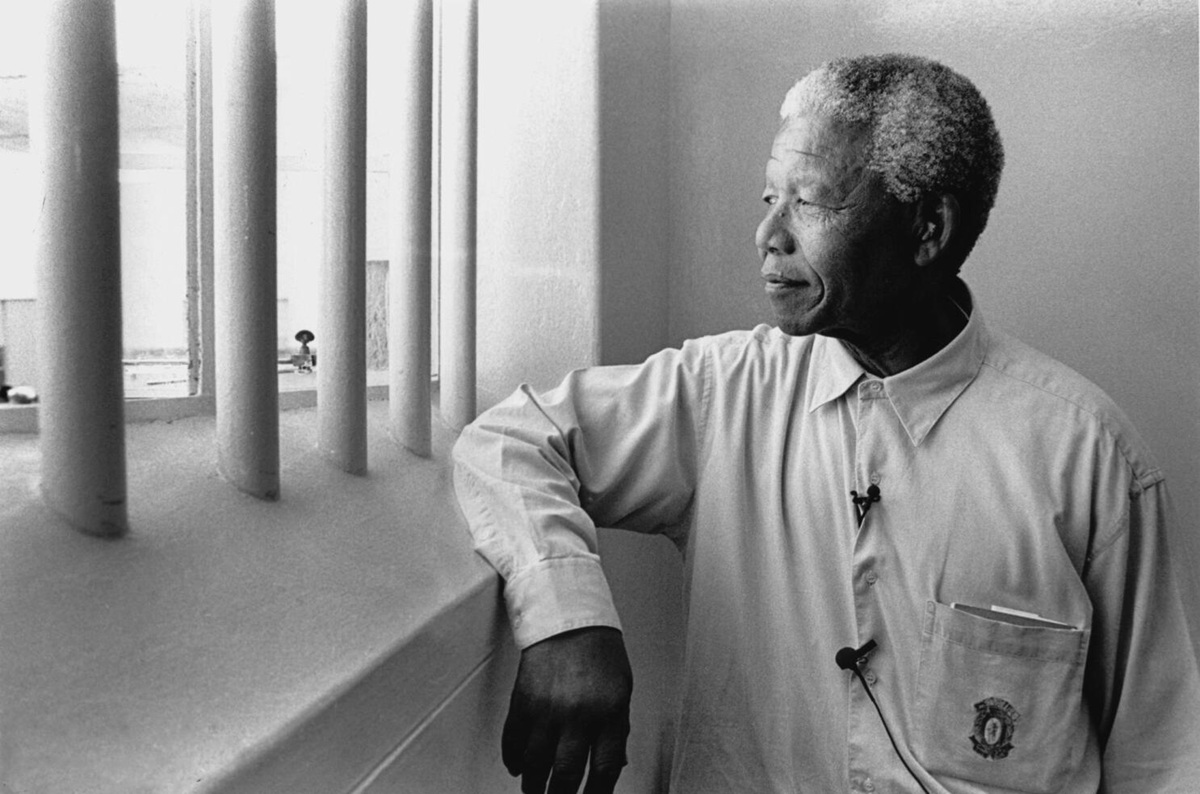

Robben Island is inextricably linked to Nelson Mandela, who spent 18 of his 27 years in a small cell, Cell 5 in Section B. Prison conditions were designed to degrade, humiliate, and demoralize political prisoners.

Prisoners were forced to work hard in the island’s lime quarry, work that caused permanent health damage, especially for Mandela, who suffered from poor eyesight. Also, there was marked discrimination among prisoners based on race; Black African prisoners (particularly political prisoners) received the worst food and clothing and minimal health care, correspondence, and visitation rights, compared to colored and Indian prisoners. Furthermore, the prison system prevented prisoners from education and study as part of an attempt to strip them of their dignity and stifle their struggle.

Despite the repression, the island was not just a place of imprisonment; it became a center of intellectual and political resistance. Political prisoners, including Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, and Jacob Zuma, worked secretly to establish what they called the “Robben Island University.” These leaders, many of whom were lawyers and teachers, organized seminars and discussions on politics, economics, history, and philosophy. This clandestine activity represented a resistance to ignorance and oppression, maintained morale and unity among the prisoners, and enabled a new generation of political activists to develop their leadership skills.

After Nelson Mandela’s release in 1990 and the end of apartheid, the maximum security prison on Robben Island was closed in 1991, and the medium-security penitentiary section was finally closed in 1996. In 1999, UNESCO declared Robben Island a World Heritage Site, considering it a symbol of the triumph of the human spirit over oppression. This classification justifies the universal value of the site, which clearly represents the history and impact of apartheid and demonstrates the will of political prisoners to achieve democracy and freedom.

The entire island has been transformed into a living museum (Robben Island Museum), with daily guided tours. The most important and impartial aspect of these tours is that the tour guides are often former political prisoners who spent many years inside the prison. This ensures that the historical narrative presented to visitors is a direct and personal testimony to the horrors of imprisonment and the resilience of the detainees, preventing the repetition of the official narrative of oppression.

The tour includes visits to Mandela’s cell, the lime quarry, and the various guard sections, allowing visitors to understand the harsh conditions experienced by the inmates.

Robben Island today represents a stark contrast between its natural beauty and its painful past. The island remains a meaningful symbol in South Africa and beyond: a tangible reminder of the immense sacrifices made by African National Congress activists and other anti-apartheid activists. The island also works to convey a story of resistance and tolerance to new generations, emphasizing the need to protect human rights and equality. The island continues to face challenges related to preserving its historic buildings, built in a harsh marine environment, and preserving the authentic narrative of the prisoners’ stories in the face of tourist development.