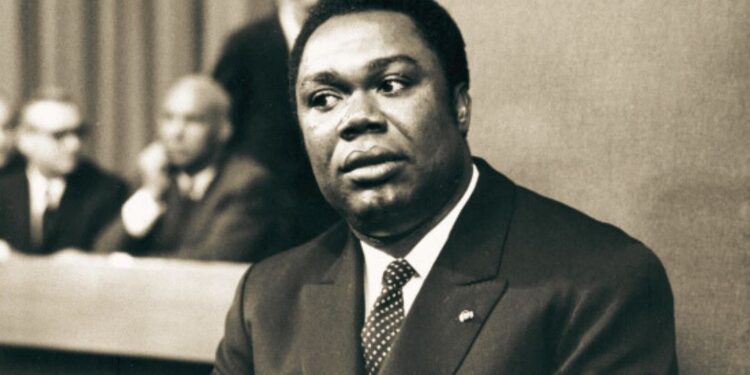

David Dacko occupies a complex position in the political history of the Central African Republic. As the country’s first president after independence, and then his return to power a decade and a half after his overthrow, his political trajectory largely reflects the instability and foreign intervention that characterized the nascent state’s history. An analysis of his reign offers insight into the challenges his nation faced during its formative stages, from building state institutions to managing internal and external political balances.

David Dacko was born on March 24, 1930, in the village of Botchanga, located in the Ubangi-Shari Prefecture, then part of French Equatorial Africa. He belonged to the Mbaka ethnic group. He received his primary education in Bangui, then moved to the teacher training school in Mobaye, graduating and working as a school principal in Bangui.

Dacko began his political career under the auspices of his cousin, Barthélemy Boganda, a charismatic figure and leader of the Ubangi-Shari independence movement. Boganda was the founder of the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa (MESAN), the country’s dominant political party. Dacko joined the party and quickly became close to Boganda, leveraging this relationship to advance his political career. After winning a seat in the regional legislative assembly in 1957, he held several ministerial positions in Boganda’s government, including the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of the Interior.

Boganda’s sudden death in a plane crash in March 1959 marked a crucial turning point. Amid the struggle for succession, Dacko, with the support of French troops and local businessmen who viewed him as a more moderate and approachable figure than other contenders, was able to assume the presidency of the government. When the country gained independence from France on August 13, 1960, David Dacko became the first president of the Central African Republic.

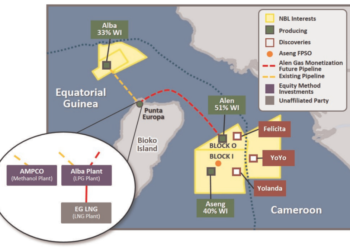

From the outset, Dacko faced significant challenges. The country lacked the infrastructure, strong government institutions, and educated cadres to govern the country. Economically, the republic was almost entirely dependent on France and on limited exports of diamonds, cotton, and coffee.

Politically, Dacko quickly moved to consolidate his power and marginalize the opposition. In 1962, he made his party (MESAN) the sole legal party in the country, establishing a one-party system. Opposition leaders, such as Abel Nguéndé Goumba, were arrested, and any form of independent political expression was suppressed. Dacko justified these measures by the need to maintain national unity in the face of ethnic and political divisions, a common justification for many post-independence leaders in Africa.

Economically, Dacko attempted to diversify sources of income, but his efforts were not met with great success. His first term in office witnessed marked economic decline, with widespread administrative corruption, mounting debt, and the failure of development plans to achieve their objectives. His government relied heavily on financial and military support from France to maintain its stability.

One of his most notable foreign policy decisions was the establishment of diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China in 1964, which angered some conservative circles at home and in France. However, the relationship with Paris remained a cornerstone of his foreign policy.

By the end of 1965, the country was on the verge of bankruptcy. Salaries for civil servants and the army were continually delayed, leading to public discontent. In this tense context, the army chief of staff, Colonel Jean-Bédel Bokassa, also a relative of Dacko, began plotting a seizure of power.

On the night of December 31, 1965, to January 1, 1966, Colonel Bokassa (Emperor Bokassa I) carried out a bloodless military coup, known as the “Saint-Sylvestre coup d’état.” The army seized vital sites in the capital, Bangui, and Dacko was placed under house arrest. Initially, Dacko was forced to formally resign and then imprisoned for several years before Bokassa released him and appointed him as his personal advisor in 1976, a move apparently intended to legitimize his regime, which later became an empire. Dacko remained in this ceremonial position until Bokassa’s fall.

After thirteen years of mismanaged rule, Emperor Bokassa I was removed from power in September 1979. His overthrow was the result of a direct French military intervention known as “Operation Barracuda.” This operation restored David Dacko to the presidency; he was flown from Paris to Bangui by French troops.

Dacko’s return to power was controversial from the outset. Many in the Central African Republic viewed him not as a savior, but rather as a figure imposed by France to ensure the continuation of its interests. His new government faced strong opposition from political figures who had fought against Bokassa’s regime, such as Abel Gomba and Ange-Félix Patassé, who saw Dacko’s return as undermining the people’s aspirations for genuine democratic change.

Dacko attempted to establish a multi-party system under popular and French pressure. In March 1981, presidential elections were held, with Dacko winning 51.1% of the vote amid widespread allegations of fraud. The election results sparked protests and riots in the capital, exposing the depth of political divisions and the fragility of Dacko’s legitimacy.

During his short second term, the economy continued to deteriorate, and instability deepened. Dacko failed to unify the country or address the structural problems he inherited from Bokassa’s regime. He remained heavily dependent on the French military presence to maintain his regime, weakening his sovereignty and ability to make independent decisions.

The Second Coup and the Later Years

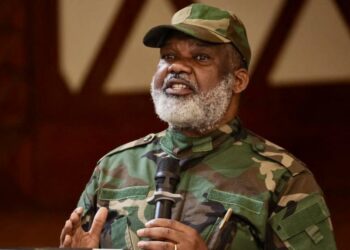

Less than two years after his return, and amid growing political unrest and economic instability, David Dacko was ousted again in a bloodless military coup on September 1, 1981. This time, the coup was led by Army Chief of Staff General André Kolingba, who suspended the constitution and banned political parties.

After his second ouster, Dacko was allowed to remain in the country but was placed under house arrest for a period. With the return of multiparty politics in the early 1990s, he attempted a political comeback. He founded his own party and participated in the annulled 1992 presidential elections and then in the 1993 elections, won by Ange-Félix Patassé, with Dacko coming in third. He also ran unsuccessfully in the 1999 elections.

In his later years, Dacko became a minor political figure, although his voice remained heard on occasion. He participated in the 2003 National Dialogue following the ouster of President Ange-Félix Patassé.

David Dacko died on November 20, 2003, in Yaoundé, Cameroon, after a long illness, at the age of 73.