The notion of technological leapfrogging is grounded in the assertion that some emerging countries can acquire and develop the necessary technical and managerial know-how that enables them to leapfrog older vintages of technology by skipping investments in old and inefficient technologies forfuture technologies. In a similar vein, technological leapfrogging is a process through which newly emerging countries circumvent the resource-intensive and expensive form of economic development by skipping to “the most advanced technologies available, rather than following the same path of conventional energy development that was forged by the highly industrialized countries.” Technological leapfrogging entails not only the skipping over generations of technologies, but it also means jumping ahead to become a leader.

Historically, hydropower has been essential to Africa’s energy generation, as shown by major projects like Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam, projected to produce 6,450 MW. Large-scale dam projects may displace populations and disrupt local ecosystems, necessitating careful planning and stakeholder engagement to mitigate negative impacts.According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), Africa has 60% of the world’s best solar resources but only 1% of solar generation capacity. To achieve its energy and climate goals, Africa needs $190 billion of investment a year between 2026 and 2030, with two-thirds of this going to clean energy, the IEA says. The World Bank, the IEA, and other partners, including the United Nations, recently called for developed economies to provide more support to develop the energy and renewables sectors in developing economies, including Africa.

About 565 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa lack electricity—representing about 85% of the global population without power. This makes off-grid solar power a “cornerstone of Africa’s energy future,” especially in rural areas, said Stephen Kansuk, the United Nations Development Programme’s regional technical advisor for Africa. It’s scaling up rapidly, and an initiative by the World Bank and African Development Bank is expected to provide off-grid solar electricity access to about 150 million people by 2030, helping to power health clinics, schools, and more, he said. “Solar energy is…a powerful instrument for climate adaptation and resilience,” Kansuk said. “Communities facing the brunt of climate change—droughts, floods, heat waves—are often the same ones with limited or no access to reliable electricity.”

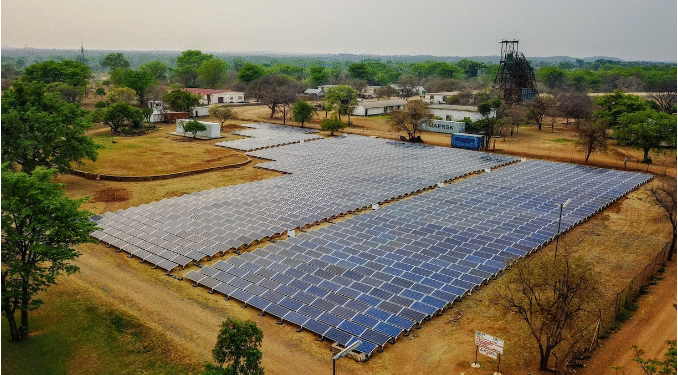

Africa is blessed not only with abundant solar resources but also with abundant land and a rich endowment of critical minerals. The development of a solar energy industry has the potential to usher in broader development of a solar economy in Africa, while simultaneously multiplying African development imperatives as outlined in Agenda 2063. In June 2021, the region reached an unprecedented milestone with 1.88 gigawatts (GW) of large-scale solar projects under development. Although South Africa has traditionally led solar adoption, nations such as Zimbabwe, Zambia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, Namibia, Ethiopia, Botswana, and Nigeria are all projected to exceed 1 GW of solar capacity soon.

The announcement of 40 GW worth of new solar projects during the year, representing a 21 percent increase from 2023, highlighted a strong commitment from governments and private investors to accelerate solar deployment. This expanding project pipeline reflects a growing recognition of solar energy as a key driver for addressing energy poverty and catalyzing economic development. Meanwhile, the task ahead is enormous. Reaching universal, affordable access will require connecting 90 million people each year, three times more than the current rate, the International Energy Agency estimates. The African Development Bank puts the cost of investment at $64bn annually. The solar PV industry, like many others in Africa, is characterized as underserved, under-exploited, or underutilized with potential for growth.

A Growing Energy Landscape

Although technological diffusion to both low-income countries and advanced countries has historically been a lengthy process. Recent studies indicate that the “pace of technological progress is determined mainly by the speed with which already existing technologies are adopted, adapted, and successfully applied domestically, and done so throughout the economy, not just in the main cities.” Across a range of technologies, the adoption period has shortened significantly in recent years leading to the introduction of cutting-edge technologies to the developing world and isolated communities

Recent statistics indicate that fossil fuels provide a substantial share of Africa’s energy production, with coal, oil, and natural gas representing over 70% of the overall energy composition. Countries such as South Africa and Nigeria are significantly dependent on coal and natural gas for energy production. In South Africa, almost 80% of energy is produced by coal-fired power plants, which significantly contribute to economic activity and considerable greenhouse gas emissions. Nigeria’s energy industry is primarily powered by natural gas, which constitutes over 90% of its electricity output, despite the country’s significant renewable energy potential.

The Africa Market Outlook for Solar PV 2025-2028 reveals that in 2024, Africa installed 2,402 MW of new solar capacity. While this marks a decrease from 3,076 MW in 2023, the shift reflects a broader regional market transformation, with emerging markets displaying remarkable growth.

South Africa, home to 46% of the continent’s new solar installations in 2024, per the Global Solar Council, is a leader in Africa’s ascent towards the utilization of renewable energy resources, followed closely by Egypt at 29%. Both countries could hold the key to Africa’s most ambitious energy projects. South Africa offers a variety of solar systems to cater to different needs, including on-grid, off-grid, hybrid, solar water heaters, and solar pumps. On-grid systems are connected to the electricity grid, allowing excess energy to be fed back into the grid. Off-grid systems operate independently of the grid, requiring a battery bank to store excess energy. Hybrid systems combine aspects of both, featuring grid connection and battery storage. Solar water heaters and solar pumps utilize solar energy for heating water and pumping water, respectively.

West Africa saw rapid growth, with Ghana (94 MW), Burkina Faso (87 MW), and Nigeria (73 MW) emerging as key players. Ghana nearly quadrupled its installations, while Burkina Faso’s market grew 129% year-on-year. Zambia (69 MW) doubled its solar capacity, a critical shift as droughts disrupt the country’s hydropower supply. Angola, Ivory Coast, and Gambia all made the top 10 for the first time, marking a clear expansion beyond the region’s traditional solar powerhouses. Policy changes will help attract much-needed investment, but aging power grids, in some cases dating back to colonial times, will need to be overhauled and new transmission lines laid down. Africa’s average transmission and distribution losses hover at about 20 percent, compared with nearer 5 percent in developed countries.

Global geopolitics is significantly shaping the energy trajectories of several African countries. Russia’s war in Ukraine, which has pushed up fuel prices, has in turn affected countries that are dependent on diesel-guzzling generators. Russia has also exerted growing influence on the energy policymaking of a crop of Sahelian countries seeking to realign away from former colonial rulers. Much of Africa’s energy inequality has deep roots in colonial-era systems, which prioritized urban elites and extractive industries, leaving rural populations excluded, a pattern that remains entrenched. Often remote and deeply impoverished, such areas are home to more than 80 percent of those without power, where mini-grids and standalone solar systems are often the best solutions.

All this requires energy transitions to meet two complex—and sometimes seemingly contradictory—goals: expanding access and shifting to low-carbon systems. There are quick wins to be had in moving to green energy, which already accounts for 55 percent of the continent’s energy needs. Abundant sunshine and rapidly developing new technology are pushing many African countries to make the switch. Energy storage is emerging as a game-changer for Africa’s solar sector, with installed capacity experiencing an exponential rise in 2024. From a threefold increase in 2023, storage capacity soared tenfold in 2024, reaching 1,641 MWh.

Unlocking Potentials: the Barriers and Solutions

Insufficient regulatory frameworks and investment obstacles are hindering Africa’s efficient transition to renewable energy. Initiatives such as green bonds and public-private partnerships may stimulate investments in renewable energy projects. The African Development Bank’s Desert to Power initiative aims to harness solar energy across the Sahel region, with a total capacity of 10 GW by 2025. Renewable energy has emerged as a crucial driver of economic development in Africa, addressing energy poverty while promoting job creation, enhancing local economies, and facilitating sustainable growth. The transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources offers unique opportunities for developing resilient economies and mitigating the adverse impacts of climate change.

At the international level, multilateral financial institutions play an important role in facilitating long-term financing to support investment in climate change mitigation. In addition to identifying alternative sources of funding, these institutions provide tailored advice on the effective deployment of climate financing. Solar home systems are already transforming households: between 2011 and 2015, pico-solar product sales skyrocketed from less than half a million to 11.3 million, with Sub-Saharan Africa now representing 70 percent of global sales. Markets in Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Nigeria lead this off-grid solar market, which has attracted significant investment.

Globally, solar growth is largely government-driven, with large-scale projects increasing energy supply at low costs. In Africa, however, over 65% of new solar capacity comes from commercial and industrial projects, driven by private-sector economics rather than public initiatives. For instance, the Royal Dutch Shell invested in SolarNow in 2017, supporting solar home systems in Uganda and Kenya. Moreover, the European Investment Bank followed with a $25 million deal for d.light in 2018, and Japan’s Mitsubishi Corporation joined a $50 million funding round for BBOXX, a provider of pay-as-you-go solar solutions, in 2019. That same year, Marubeni Corporation invested $26 million in Azuri Technologies, highlighting growing investor confidence in the sector’s promise.

While a Kenya-based solar power company is banking on using an $80 million loan from the World Bank’s private investment arm to meet its target of tripling sales in the world’s most electricity-deprived country within the next few years. The amount of new financing raised by solar power company Sun King for its Kenya business. It will enable the business to continue its model of allowing customers to buy products, such as solar lanterns and home appliances, by making small payments over a period of up to two years.

Similarly, the financing was secured from five banks and three development financiers, including British International Investment. Sun King estimates that nearly a third of Kenyans use its products. It said the new financing will extend its reach to 1.4 million low-income households and businesses. The company’s Africa footprint includes Nigeria, where it aims to triple sales within the next few years after securing an $80 million World Bank loan.

Solar energy presents numerous advantages, especially for rural communities traditionally relying on costly, inconsistent sources. Solar power supports local job creation, contributing to economic development in areas with high unemployment, and offers a carbon-free alternative critical for climate resilience. However, the sector also faces challenges, such as limited grid capacity and transmission infrastructure that can hinder distribution. Additionally, financing remains a significant barrier for smaller developers, and regulatory frameworks across some nations need harmonizing to encourage investor confidence. Addressing these issues is essential to maximize solar’s impact across the region.

Africa’s solar expansion is being held back by capital costs that are 3 to 7 times higher than in developed countries. While clean energy investment doubled to $40 billion in 2024, Africa still accounts for just 3% of global energy investment—far from the $200 billion per year needed to achieve energy access and climate goals. “There is no shortage of excellent solar resources and political ambition in Africa—only a shortage of affordable capital,” said Léo Echard, policy officer at GSC and lead author on the report. “Many projects are struggling to secure financing because of high interest rates, currency risks, and lack of guarantees. If we can reduce the cost of capital, Africa could become one of the fastest-growing solar markets in the world.”

Looking Ahead

As solar-based electricity remains a pricey proposition for many in Africa. The upfront cost of setting up panels, batteries, and an inverter to provide half-a-day power for a Nigerian household can be up to $4,000, which could make the service out of reach for a minimum wage earner. All the same, the potential for solar in sub-Saharan Africa is immense. IRENA estimates the region could generate up to 10 terawatts (TW) of solar power. With adoption rates expected to exceed 20 percent annually through 2025, as projected by the International Energy Agency (IEA), solar could reshape Africa’s energy landscape.

Even so, only 44 percent of the region currently has electricity access, highlighting the importance of initiatives like the African Union’s goal for renewables to comprise over 30 percent of the energy mix by 2030. With sufficient support, solar energy could redefine Africa’s energy future, addressing energy poverty and promoting sustainable economic growth. Outdated assumptions and perspectives among policymakers have, however, hindered the continent’s ability to fully exploit this opportunity and prevent Africa from positioning itself as an early mover to reap the maximum benefits of a thriving solar economy. With a shift in mindset and the implementation of forward-thinking policies, Africa can change this and unleash its solar potential. The continent has the potential to attract substantial investments and emerge as a pioneer in the renewable energy revolution, with broad development benefits.

Africa is poised for an energy change due to advancements in energy storage, enhanced grid infrastructure, and regional collaboration. These factors will alleviate the intermittency issues linked to renewables and realize the whole potential of cross-border energy commerce. As Africa progresses down this path, it will not only fulfill its energy requirements but also establish itself as a global leader in renewable energy innovation, building a paradigm for sustainable development and climate resilience globally. A report noted that expanding innovative financing mechanisms, de-risking instruments, and private sector investment can lower the cost of capital for solar PV. While strengthening policy and regulatory frameworks to attract private sector investment. While strengthening policy and regulatory frameworks to attract private sector investment.

In addition, governments could incentivize local construction firms to install solar systems in new infrastructure projects. Such actions would provide a much-needed boost for the industry and create jobs in areas such as construction, installations, and repair services. As countries strive to facilitate this technological leapfrogging, there is a need to remove restrictions on the adoption of solar generation, such as access to finance for the local area, government support programs, and education to raise awareness of the technologies available.