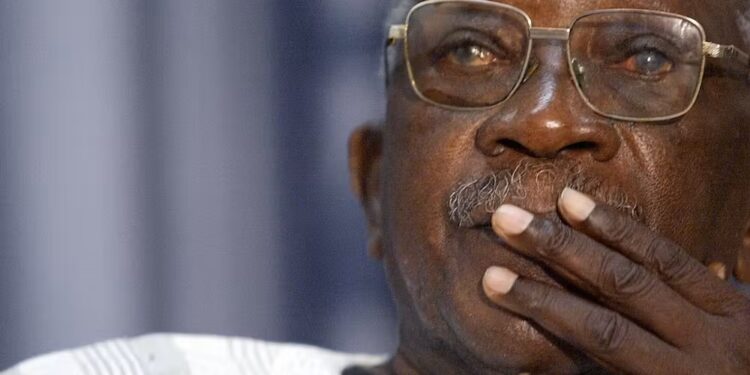

Ousmane Sembène was born on January 1, 1923, in Ziguinchor, in the Casamance region of southern Senegal. He belonged to the Lebo community, whose members traditionally work as fishermen, a profession his father followed. His educational path was short-lived; after a brief stint at a French school, he was expelled due to a dispute with a teacher. This early interruption of formal education marked a turning point, propelling Sembène toward a path of self-education and reliance on life experiences as a source of knowledge.

As a young man, Sembène worked in various manual jobs, including as a mechanic and a bricklayer, giving him a firsthand understanding of the lives of the Senegalese working class. In 1944, he was conscripted into the French army to fight in World War II as part of the Tirailleurs Sénégalais (Senegalese Riflemen). His military experience took him to the Congo and North Africa, then to Europe to participate in the liberation of France. This period was crucial in shaping his political consciousness. It allowed him to see the stark contradictions of the colonial system, which required Africans to sacrifice their lives for a “freedom” that did not include them. It also revealed to him the discriminatory treatment African soldiers faced compared to their French counterparts, an experience he would later recount in his film, Camp de Thiaroye.

After his discharge from the army, Sembène chose to remain in France rather than return to Senegal. He settled in Marseille and worked as a port worker for more than a decade. This period was a period of intense intellectual formation. He became involved in trade union activism within the General Confederation of Workers (CGT) and joined the French Communist Party. Through these affiliations, he delved deeply into Marxist thought and theories of class struggle and anti-imperialism. At the same time, he was an avid reader, independently studying world literature, philosophy, and history, compensating for his limited formal education. The migrant worker’s experience, accompanied by racism and exploitation, as well as his political and intellectual engagement, formed the raw material for his early literary works.

Sembène began his literary career in France, inspired by his personal experience as an African migrant worker. His early writings were a direct reflection of his life circumstances and his critical perspective on relations between Africa and Europe.

His first novel, “Le Docker Noir” (The Black Worker), was published in 1956. The autobiographical novel tells the story of Diaw Fala, a Senegalese dockworker in Marseille who writes a novel about the suffering of his people, but a French writer steals it and publishes it under his own name. When Diaw confronts him, the confrontation ends with the French writer’s death, and Diaw is sentenced to life imprisonment. The novel explores themes of racism, economic exploitation, and injustice within the French judicial system. It also highlights the difficulties faced by African intellectuals in expressing their voice within a dominant European cultural structure.

In his second novel, “O Pays, mon beau peuple!” (My Beautiful People!) (1957), Sembène shifted the focus from France to Senegal. The protagonist is Omar Faye, a former soldier who returns to his village in Casamance with his white French wife and attempts to introduce modern agricultural methods and establish a cooperative to counter the dominance of colonial traders. His reformist ambitions encounter twofold resistance: from the colonial administration, which views his activism as a threat to their interests, and from some members of his community, who cling to tradition and are suspicious of his intentions. The novel ends tragically with Omar’s death. Through this story, Sembène addresses the problem of the “returnee,” a person who harbors progressive ideas but fails to effect change due to the power of existing structures, whether colonial or traditional.

Sembène’s most notable literary work is Les Bouts de bois de Dieu (The Remains of God’s Wood), published in 1960. The novel deals with a real historical event: the great strike of railway workers on the Dakar-Niger line in 1947-1948, which lasted for several months. What distinguishes this novel is its multi-voiced narrative structure, as the narrative shifts between different cities (Dakar, Thiès, and Bamako) and presents the perspectives of diverse characters: from strike leaders like Ibrahima Bakayoko to ordinary workers, the elderly, and women.

One of the most important aspects of the novel is its emphasis on the pivotal role women played in the success of the strike. While men were the strikers, it was women who shouldered the burden of managing families in the absence of income and organized protests, culminating in the famous “Women’s March” from Thiès to Dakar to pressure the French authorities. Characters like Ramatoulaye and Pinda demonstrate the strength and resilience of African women as key actors in political and social struggles, not merely marginal figures. The novel is an epic of the workers’ struggle against colonial exploitation and an embodiment of the power of solidarity and collective action to achieve legitimate demands.

In later films, Sembène explored African history from an African perspective, challenging colonial narratives.

Emitai (1971) depicts the resistance of a Diola village in southern Senegal to orders from French authorities during World War II to surrender their rice crop. The film depicts the conflict between the village’s traditional religious beliefs and external pressures, highlighting the role of women as guardians of tradition and symbols of resistance.

Ceddo (1977) is an epic historical work about the resistance of the Ceddo people (common people who refused to submit to aristocratic authorities) to attempts to impose Islam on them in the 17th century. The film addresses the issue of religious imperialism, whether Islamic or Christian, and its impact on indigenous African cultural identity. The film sparked controversy with the government of President Léopold Sédar Senghor over the spelling of the word “Ceddo” and was banned in Senegal for years.

In Camp de Thiaroye (1988), co-directed with Tierno Faty Sow, Sembène revisits his World War II experience to tell the true and tragic story of the massacre of African soldiers at the Thiaroye camp in 1944. These soldiers, having returned from fighting in Europe, demanded their back pay and equal treatment with French soldiers, and the French authorities responded by shooting them. The film is a powerful condemnation of colonial brutality and a work aimed at correcting the official history that attempted to erase this crime.

Ousmane Sembène died on June 9, 2007, leaving behind a vast cultural and artistic legacy. He is often referred to as the “Father of African Cinema,” not only because he was a pioneer, but also because he laid the theoretical and aesthetic foundations for a committed and independent African cinema. He inspired and influenced generations of African directors who followed in his footsteps in using cinema as a tool for identity expression and social critique.