One of the world’s most famous ghost towns, Kolmanskop lies in southern Namibia, about 15 kilometers east of the coastal city of Lüderitz. Today, it stands as an archaeological ghost, its abandoned structures slowly being swallowed by the unforgiving sand dunes of the Namib Desert. Kolmanskop is a stark monument to the diamond boom that swept through this arid region in the early 20th century. Its history offers a unique glimpse into the era of German colonialism in Africa, into the stark contrasts in lifestyles between European settlers and local workers.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the area that would later become Namibia was a German colony known as German South-West Africa. The region was vast, sparsely populated, and largely considered to have little economic value, except for some agriculture and strategic ports such as Lüderitz. This perception changed radically in 1908. August Stauch, a German railway official, was appointed supervisor of a stretch of railway that ran through the desert near Lüderitz. Stauch, who suffered from asthma and was advised by doctors to avoid the dry desert air, had an interest in mineralogy and instructed his workers to search for any unusual stones they might find.

On April 14, 1908, while clearing sand from the railway tracks, a worker named Zachariah Luala discovered a shiny stone. Luala had previously worked in the diamond mines of Kimberley, South Africa, and realized the stone might be valuable. He presented the stone to Stauch, who took a sample for testing. When it was confirmed that the stone was indeed a diamond, Stauch realized the enormous significance of the discovery. He acted quickly, quietly obtaining prospecting licenses for a vast area of desert land surrounding the discovery site.

The secret of the diamond discovery was short-lived. News spread quickly, sparking a diamond fever. Prospectors, adventurers, and fortune-seekers from Germany, other parts of Europe, and neighboring South Africa flocked to the arid region. Early reports described the abundance of diamonds as incredible. The gems were scattered across the desert surface, glistening in the moonlight, and in some places could be collected by hand. These deposits were alluvial diamonds, carried by ancient rivers to the ocean and then brought back to shore by winds and deposited in the desert over millions of years. The ease of their extraction initially fueled the discovery frenzy.

To control this newfound wealth and prevent uncontrolled prospecting, the German colonial government quickly declared a vast 26,000-square-kilometer area of the southern Sahara a restricted area, or “Sperrgebiet.” Entry to this area was permitted only with a special government permit. Within this restricted area, several mining companies were established, the most prominent of which was the Deutsche Diamanten-Gesellschaft (German Diamond Company). In the heart of this diamond-rich region, and a short distance from the original Luala discovery site, a new settlement arose. It was named Kolmanskop, after a bullock cart driver named Johnny Kolman, who was said to have abandoned his cart in the area during a sandstorm. This humble settlement began as a temporary prospector’s camp, but with the influx of wealth, it soon grew into a remarkably well-organized and prosperous town.

Kolmanskop’s transformation from a dusty mining camp into a model town was rapid and astonishing. Fueled by the enormous profits from diamond mining, the company that ran the town spared no expense in creating a German-style oasis amidst the harshness of the Namib Desert. The town was designed to provide comfort and shelter for the German employees—from managers, engineers, and geologists to doctors and teachers—who had moved to this remote corner of the empire. The architecture clearly reflected the German taste of the time, with sturdy buildings with high ceilings, balconies, and windows designed to withstand the harsh climate while maintaining an aesthetic familiar to residents. Many building materials and furniture were imported directly from Germany, enhancing the town’s distinctly European character.

The level of infrastructure in Kolmanskop was unusual for its isolated location and time. A large, well-equipped hospital was built, featuring the first X-ray machine in the Southern Hemisphere. This advanced equipment had a dual purpose: for medical diagnostics and, more importantly, for screening workers to prevent diamond theft. To meet the needs of the population, a power plant was built to provide electricity for homes, businesses, and street lighting. An ice factory, a vital luxury in the desert heat, produced blocks of ice daily to cool drinks and preserve food. Fresh water, a precious commodity in the desert, was supplied by pumping it from the desalination plant in Lüderitz or transported by rail from Cape Town in South Africa.

Life in Kolmanskop was not just about work. An impressive array of recreational and cultural facilities were built to entertain the wealthy residents. The center of social life was the lavish “Casino” (which functioned as a community hall rather than a gambling establishment). This impressive building included a large banquet hall, a theater, a gymnasium, a restaurant, and a fully equipped kitchen. The hall hosted frequent dances, theatrical productions, and concerts, and often hosted traveling bands from Europe. Alongside the casino, there was a skittles alley, a public swimming pool, a school, a bakery, a butcher shop, and a post office. The town also operated an ice train that delivered ice, sparkling water, and soda to every home daily.

However, this lavish lifestyle was reserved exclusively for the European population. The miners, mostly Ovambo people from the northern parts of Namibia, lived in very different conditions. They were housed in simple barracks separate from the main town and worked under strict contracts. Their lives consisted of hard labor in harsh conditions, with few of the amenities enjoyed by their German counterparts. This stark separation between the lives of Europeans and African workers was a defining feature of colonial society in Kolmanskop, reflecting the social and racial hierarchy of the time. Despite these contrasts, Kolmanskop thrived. At its peak, the town was home to approximately 1,200 people, including approximately 800 Ovambo workers and 400 German residents and their families. For decades, it has stood as a testament to the vast wealth that can be extracted from the earth, an exotic island of European culture and entertainment set in one of the world’s most challenging landscapes.

The seeds of Kolmanskop’s decline began to appear even as its prosperity continued. The first factor was the limited nature of the diamond deposits themselves. Diamonds around Kolmanskop were initially abundant and easy to extract, but by the end of World War I, prospectors had collected most of the surface stones. Mining increasingly required heavy equipment and more expensive drilling operations to reach the deeper deposits. Profitability declined, and the exceptional density of diamonds that had led to the town’s establishment began to diminish.

Political change was also a contributing factor. Following Germany’s defeat in World War I, South Africa assumed administrative control of South West Africa under a League of Nations mandate. Although mining operations continued under new management, the close relationship between the German colonial administration and mining companies had changed. Global economic dynamics also began to shift. The Great Depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s led to a sharp decline in world diamond prices, reducing the profitability of Kolmanskop’s increasingly expensive operations.

However, the final blow to Kolmanskop was a stunning new discovery in 1928. The world’s richest alluvial diamond deposits were found about 270 kilometers south of Kolmanskop, in the beach terraces near the mouth of the Orange River. These new deposits, discovered by Hans Merensky, were larger and of higher quality than those found around Kolmanskop. This discovery marked a radical shift in the focus of the diamond industry in the region. Mining companies, including Consolidated Diamond Mines (CDM), which had absorbed several former German companies, quickly shifted their attention and resources south.

The lure of the richer new fields led to a mass exodus from Kolmanskop. Miners, engineers, and families began packing up and moving south to new mining towns such as Oranjemund, established near the newly discovered deposits. The abandonment was gradual but relentless. Businesses closed, and valuable equipment was moved to new mining sites. The services that made life in the desert possible began to cease. The hospital closed, the school emptied of its students, and the ice factory ceased production. There was no longer any economic reason to maintain this expensive artificial oasis.

By the 1940s, Kolmanskop was a shadow of its former self, with only a handful of residents remaining. Small-scale mining continued in the surrounding area for a time, but the town itself was dying. The last remaining families left in 1956, after which Kolmanskop was completely abandoned to the desert. Buildings that had once been full of life, laughter, and music were left empty and silent. The relentless wind, always a constant enemy, began its mission to reclaim what had been its own. Sand began to drift over window sills and through doorways, beginning the slow but unstoppable process of burying the town.

As soon as the last inhabitant left, the Namib Desert began to reclaim Kolmanskop. The strong, constant winds in this area act as a tireless natural engineer, carrying tons of sand from the surrounding dunes and depositing it inside the abandoned buildings. What were once palatial dwellings are now filled with sand, with small dunes rising inside the rooms, partially covering the floors, and spilling down the hallways. This interplay between man-made architecture and the natural environment creates a surreal and poignant scene that has become Kolmanskop’s hallmark. The brightly painted walls, now faded and peeling from the sun, stand in stark contrast to the golden sand filling the interior spaces. Doors hang from their hinges, broken windows swing in the wind, and collapsed roofs reveal the skeletons of buildings.

The extremely dry climate of the Namib Desert, though harsh, has played a crucial role in preserving the city’s remains. The scarcity of moisture and rain has significantly slowed the process of decay and decomposition. As a result, many of the interiors, including wallpaper, paint, and woodwork, have been remarkably well preserved beneath layers of protective sand. This preservation allows visitors to glimpse daily life and aesthetics during the town’s heyday. One can wander through the bowling alley and see the wooden arcade still intact, gaze at the remains of the casino’s gymnasium, or imagine schoolchildren studying in classrooms now filled with sand.

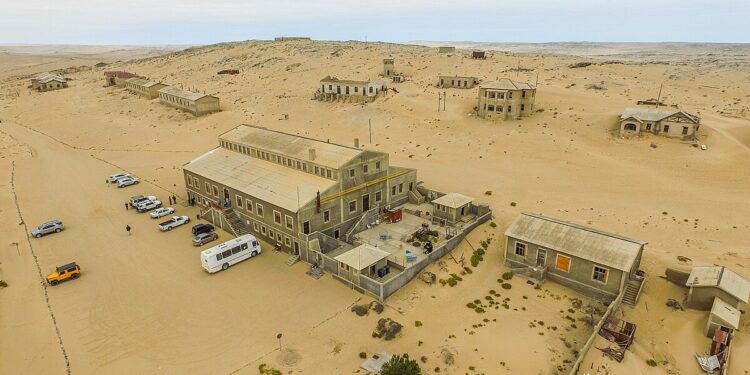

For a long time after its abandonment, Kolmanskop remained closed to the public, protected within the restricted Sperrgebiet area. However, in the 1980s, the mining company De Beers (which operated through its subsidiary CDM, later to become Namdeb in partnership with the Namibian government) recognized the site’s potential tourism value. A few buildings, including the casino, were partially restored for use as a visitor center and museum, and the town was opened for guided tours.

Today, Kolmanskop is a popular tourist destination and a haven for photographers. The contrast between the majestic European architecture and the raging desert sands attracts artists and filmmakers from around the world, who come to capture its haunting beauty. The town has been featured in numerous films, documentaries, and music videos, cementing its status as one of the most visually striking ghost towns in the world. Exploring the town requires a permit, and visitors can join daily tours that explain the town’s history or obtain special permits to explore at sunrise and sunset, when light and shadows create particularly dramatic scenes.

The future of Kolmanskop raises questions about preservation. There is an ongoing debate about how much intervention should be made. Should the town be preserved as it is, a deteriorating monument, and nature allowed to slowly take its course? Or should more efforts be made to restore buildings and protect them from the encroaching sand? For now, there appears to be a balance: a few key buildings are being preserved to maintain their structural integrity and provide a tourist experience, while the rest are allowed to slowly succumb to the desert.