Situated in the Horn of Africa and with close relations with civilization and international trade, Somalia was of great interest to European and Arabian powers. European interest began in 1939 when Britain began to use Aden as a coaling station for ships to India, and France and Italy for their coaling services as well. When the scramble for Africa began in the 1880s, Britain, France, and Italy, alongside Ethiopia, wanted Somalia. France received the region around Djibouti, which became formally known as French Somaliland, from Britain. Italy received the territory by the coast, which became known as the Italian Somaliland. Britain’s territory was known as the Somaliland Protectorate.

The race for bases and ports in the Horn of Africa is well underway. Somalia hosts Turkey’s largest overseas military base, and Turkish companies run Mogadishu’s port and airport. Turkey’s ally and benefactor, Qatar, is also working to establish itself in southern Somalia. Further north in the independent but unrecognized Republic of Somaliland and in the autonomous region of Puntland, United Arab Emirates (UAE)-based companies operate the ports of Berbera and Bosaso.

The UAE has also built a naval and air base at Assab in Eritrea. Djibouti, wedged between Somaliland and Eritrea, hosts bases for the United States, Japan, France, Italy, and China. According to experts, these great powers often prioritize strategic interests over humanitarian and developmental considerations, perpetuating and exacerbating the region’s instability.

The reasons for growing interest in the Horn of Africa are twofold: first, the countries that make up the Horn of Africa (Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, and Ethiopia) are regarded as the eastern door to Africa and its abundant natural resources. Somalia, Djibouti, and Eritrea all have coastlines that border what is arguably the world’s most important shipping corridor.

In 2018, an estimated 6.2 million barrels per day of petroleum products passed through the 30-kilometer strait, the Bab al-Mandeb, which is located between Eritrea, Djibouti, and Yemen. Second, Gulf States—primarily the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar—want the strategic depth that greater involvement in the Horn of Africa may deliver.

The frequent presence of military facilities alongside harbor investments is another telling factor. Although oft-cited piracy and terrorism concerns cannot be dismissed, numerous Western naval units have for years been patrolling the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. Consequently, the Emirati, Qatari, and Turkish footholds around East African ports seem aimed at controlling strategic hotspots and the ouster of regional rivals.

Giorgio Cafiero, the CEO of Gulf State Analytics, a Washington, DC-based geopolitical risk consultancy, notes that Africa’s east coast now sees a spate of port development projects supported by rival powerhouses and often coupled with military infrastructure. Evidently, the geopolitics of ports can negatively impact regional peace and maritime security.

After the lost years with Boris Yeltsin, the Russian foreign policy concept shifted in Putin’s presidency. Russia has projected its hard and soft power as a great power in Africa again. Russia’s trade with Africa has increased immensely in recent years. Russian armed forces have been involved in peacekeeping operations in Africa. Still, Africa is not at the center of Russian foreign policy. But the developments in the Gulf of Aden can make Russia more eager to concentrate on the Horn of Africa.

There have been reports previously of Russia’s intent of setting up a naval base in the Horn of Africa, with the Port of Berbera in Somaliland high on the list. Analysts also indicate that with the new Syrian government likely to kick the Russians out of their base in Tartus, Port Sudan would be Russia’s only foreign naval base. Looking ahead, Russia’s ability to link its Horn of Africa strategy to its aspirations in the Middle East will shape the future trajectory of its involvement in the region.

The Intriguing Tapestry of Russian and Somali Diplomatic Ties

Although the Russian Empire took fleeting interest in Africa through the establishment of a colony in Sagallo, Djibouti, in 1889 and provided doctors to Ethiopia during the 1890s, Moscow’s influence on the continent was peripheral until Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953. Decolonization provided an opening for the Soviet Union to emerge as a superpower in Africa.

Russia, inheriting the USSR’s influence, has reestablished ties with countries it supported during the Cold War, such as Angola, the Central African Republic, and Mozambique. These relationships are marked by military cooperation and economic investments. Apparently, Russia employs a two-tier approach in Africa.

One is a long-term official approach that focuses on achieving Russia’s foreign policy objectives by using traditional political, economic, and military-security tools, while another is an unofficial approach that focuses on shorter-term political and economic gains by using private military corporations (PMCs) linked to Russia.

Meanwhile, Russian–Somali relations is the bilateral relationship between Russia and Somalia. Somalia has an embassy in Moscow. While the Russian Embassy in the Republic of Djibouti represents Russia in the Federal Republic of Somalia concurrently. Diplomatic officials say, by working together, Somalia and Russia hope to create safer communities and secure a peaceful future for generations to come. Both Somalia and Russia recognize the potential for extensive collaboration and are committed to building upon their existing relationship.

Although Moscow has viewed the Horn of Africa as a valuable theater for power projection since the 1930s, the Soviet Union only emerged as a major player in the region during the early 1960s when it established close relations with Somalia. This partnership was strengthened by the Marxist-Leninist ideological orientation of Somalia’s President Siad Barre, who assumed power in a 1969 coup d’etat. The Soviet Union supported Djibouti’s independence in June 1977 and forged close relations with President Hassan Gouled Aptidon.

The Soviets were providing political advice and economic aid, as well as military training and weapons. In July 1974, the Soviet President Nikolai Podgorny paid an official visit to Mogadishu, and Somalia signed several treaties with the Soviets, including the Somali-Soviet ’Friendship Treaty on July 11, 1974.

However, the Soviets’s influence in Somalia was short-lived with the outbreak of the Somali-Ethiopian War (1977-1978), in which both Somalia and Ethiopia effectively switched sides in the Cold War. The Horn of Africa witnessed the enduring persistence of both the USSR and the US, who were happy to exploit the local war. Somalia came to a disagreement with the Soviets during the 1977-78 war, and the shifting proxies solidified the new alliance of superpowers and their geostrategic interests in the Horn of Africa.

Left without Soviet support, Somalia began to actively seek new sources to replenish the arsenals that were melting in the war with Ethiopia. Western countries refused to supply Somalis with weapons while there was a conflict, but the support was provided by Muslim countries: Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Iran. Only Egypt during the war gave Somalia military equipment for 30 million dollars.

Nevertheless, the Somali army, faced with Ethiopian troops armed with Soviet equipment and supported by Cuban units and Soviet advisers, was defeated and in March 1978 announced its withdrawal from Ogaden. The regime of S. Barre became close with the Americans. In August 1980, the United States and Somalia signed an agreement giving American warships the right to use Somali ports and the US Air Force the air bases in Berbera, Mogadishu, and Kishimayo. In exchange, the Americans supplied arms to the Somali regime.

By the late 1980s, after the Ogaden War, Barre’s policies in the north resulted in discontent amongst the Isaaq clan. (There are five major clans in Somalia—the Isaaq, Darood, Digil and Mirifle, Dir, and Hawiye—and various smaller clans.) The Isaaq were the largest northern clan, and they felt isolated from the current politics and state resources.

Some moves, such as the resettlement of Ogaden refugees in northern areas, were seen as southern attempts to subvert northern interests. There was an uprising against Barre, led by the northern Isaaq clan, and in response, Barre ordered bombings of northern towns, villages, and even rural encampments. Gradually, the uprisings would spread to the southern areas, and in 1992 Barre was forced to flee. Somalia’s defeat in the war led to a bitter blame game. This ultimately resulted in uprisings against him.

The role of international organizations is to maintain peace and order in conflicts, but sometimes, the oppositions see these as a threat to their activities. Following the collapse of Somalia’s central government, the United Nations created the United Nations Operation in Somalia I (UNOSOM 1) to provide relief to the people and restore order. In 1992, UNSC Resolution 794 was passed and approved a coalition of UN peacekeepers led by the United States to stabilize the situation in Somalia, and this started the two years of United Nations Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II).

These operations recorded some success in the country, though in 1995, the UN soldiers withdrew after incurring more casualties. The military clashes after this were more localized, as the UN military intervention did curb intense fighting in the region. The UN missions contained the war, but new uprisings arose between political parties. The African Union Mission in Somalia became active in 2007 with an initial mandate of six months, though it is still active. The operation was mandated to support transitional governmental structures, implement a national security plan, train the Somali forces, and assist in creating a secure environment.

Somalia’s New Alignments: Prospects and Challenges with Russia

Russia’s game plan in Africa has involved seeking alliances with regimes or juntas shunned by the West or facing insurgencies and internal challenges to their rule. In the meantime, Mogadishu depends on external military assistance in its battle against the advancing violent Islamist extremist group, Al-Shabaab. It also faces increasing defiance from two federal regions, Puntland and Jubaland. For decades, Somalia’s foreign policy leaned heavily toward Western countries, especially the U.S. and EU, due to support in counter-terrorism, state-building, and development aid.

Currently, there is a growing discontent in Somalia with the C6+ group—an informal international coalition including the United States, United Kingdom, European Union, United Nations, African Union, IGAD, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sweden. In April, Russia’s special presidential envoy for the Middle East and Africa, Mikhail Bogdanov, and Somali officials agreed to expand cooperation between the two countries in security, politics, trade, and economic areas, the Russian Foreign Ministry announced.

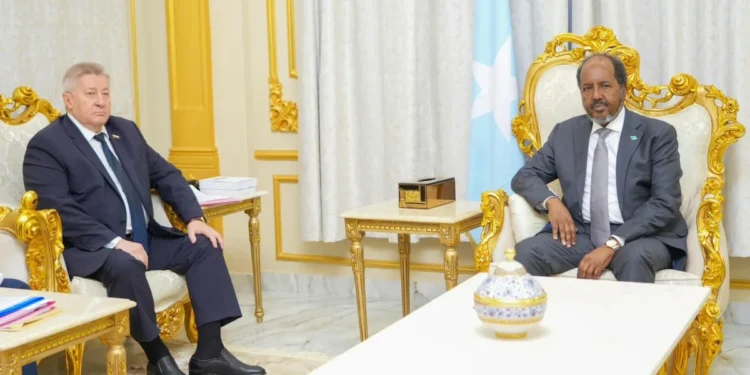

Bogdanov held talks with Somali Foreign Minister Ahmed Moallim Fiki while on an official visit to the East African country, where he was received by President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, according to the ministry. Meanwhile, “During the exchange of views on current international and regional issues, including taking into account Somalia’s membership in the UN Security Council in 2025-2026, special attention was paid to the tasks of interaction on issues of ensuring peace and security in the Horn of Africa, with an emphasis on the need to quickly eradicate the terrorist threat in the region,” the ministry stated.

Putin’s Surprising Somali Move: What It Means for the World

Russia and African countries are linked not only by friendly relations that have stood the test of time but also by the desire to make the world safer and more predictable, said Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov at a gala reception in honor of the heads of delegations participating in the ministerial conference of the Russia-Africa Partnership Forum.

“Our countries and peoples are linked not only by time-tested friendly relations but also by a shared desire to make the world we live in more secure and predictable and to ensure reliable conditions for sustainable development. We see this shared aspiration as the ideological and psychological foundation for our work within the Russia-Africa Partnership Forum,” he said last year.

Some analysts note that Russia’s growing military presence in Africa enables the Kremlin to use its limited resources to threaten NATO’s southern flank and degrade Western influence, advancing the narrative that Russia is a revitalized great power. A Russian naval base in Libya would threaten Europe and NATO’s southern flank by helping support Russian activity in the Mediterranean Sea and potentially positioning a standing Russian force able to threaten NATO critical infrastructure with long-range cruise missile strikes from the sea. Also, Russian occupation of the US drone base in northern Niger would create the opportunity for Russia to threaten NATO operations in the Mediterranean Sea with versions of the mass-produced Shahed-136 attack drone.

Evidence indicates that interstate conflicts and internal instability in the Horn of Africa are often connected, where each manifests as disputes that are tangential to the true object of conflict, such as territorial and boundary contentions, which often manifest in internationalized intrastate wars. For Somalia, strengthening ties with Moscow is an effort to diversify its international partnerships and attract new investment, infrastructure development, and security cooperation. However, for Moscow, the Horn of Africa is a region where stability, access to critical ports, and natural resources are important for global trade.

Karolina Lindén, an analyst at FOI’s Studies in African Security, notes that a Russian naval base in the Red Sea would be a possible game changer, with geostrategic implications for the EU and NATO. The Mediterranean now bears 20 percent of global shipping. As Europe turns away from Russian oil and gas, some of the replacements are coming from the African, Mediterranean, and Gulf regions. Ensuring that the Mediterranean and Red Sea routes remain open and unhindered is of strategic importance for global trade and for the EU.

Moreover, it also complements Russia’s rising influence in the Black Sea since the February 2014 annexation of Crimea, which expanded its access to the Middle East, North Africa, and Eastern Mediterranean and, together with the modernization of Russia’s armed forces (notably the Black Sea fleet), laid the foundations for Moscow’s eventual return to the Red Sea.

Observer says Somalia’s pivot to Russia is motivated by a desire to escape the political constraints tied to Western assistance. The Lansing Institute for Global Threats and Democracies Studies notes, “Russian support comes with fewer political strings attached, making it more attractive to governments that want immediate military and economic results without human rights scrutiny.” Also, the expansion of Russian-Somali ties has triggered concern in Washington, Brussels, and Gulf capitals.

Furthermore, Western officials warn that Russian arms transfers could undermine the fragile arms embargo imposed by the United Nations and disrupt ongoing counterterrorism cooperation. The Institute is of opinion that “the West fears a Somali tilt toward Russia could fracture joint operations against al-Shabaab and compromise intelligence-sharing frameworks.“ Such a shift could also affect U.S.-Africa Command (AFRICOM) partnerships and African Union-led stabilization missions.

In conclusion, neighboring powers such as Kenya and Ethiopia may also feel compelled to reassess their regional strategies. “A strong Russian presence in Somalia could tip the security architecture of East Africa,“ the Lansing Institute warns. In addition, the think tank outlines a worst-case scenario in which Somalia becomes part of a loosely coordinated bloc of Russian-aligned African states, similar to Moscow’s relationships with Sudan and the Central African Republic. Though still speculative, the trend has prompted growing concern among Western and African policymakers.