Niger is a country with over 25 million inhabitants. The name Niger derives in turn from the phrase gher n-gheren, meaning “river among rivers,” in the Tamashek language. The country ranks 189th out of 191 countries in the 2022 UN Human Development Index. Despite being the 7th largest supplier of uranium in the world, Niger also ranks 7th among the world’s poorest countries. More than 40 percent of people in the population make less than $1 a day, and two out of every three live below the poverty line set by the government. Analysts say the record of fifty years of uranium mining in Niger by subsidiaries of the French nuclear company Areva, the world’s leading civil nuclear group, until its dismantlement is illustrative. Areva’s sales have consistently far exceeded Niger’s GDP, and Niger’s mines have always been considered strategic by the company, even after the diversification of supply countries. Niger’s uranium has contributed to a third of the electricity produced by French nuclear power plants, playing a significant role in keeping it among the world’s leading economic powers. Until the present, France remains 100% dependent on Niger’s uranium for its military nuclear power.

Mohamed Bazoum, a candidate of the ruling party, was elected president in the December 2020 and February 2021 elections. He succeeded his predecessor in a democratic manner, making history. Bazoum’s government has been a partner with European countries trying to stop the flow of migrants across the Mediterranean Sea, agreeing to take back hundreds of migrants from detention centers in Libya. He has also cracked down on human traffickers in what had been a key transit point between other countries in West Africa and those further north. A State Department official in March also praised Bazoum for speaking out against Russia’s private Wagner group of mercenaries, which has been hired by Mali’s junta to help fight insurgents there. Mali describes the Wagner personnel on its territory as trainers.

Surprisingly, his presidential guard, however, fired him on July 26, 2023, citing a desire to prevent more security and economic issues as their reasons. An expert noted that “if you know anything about Niger’s troubled political history, a putsch in that country was not out of the question. There was even a serious warning just before President Bazoum came to power, because just two days before he was sworn in, a coup d’état had been foiled.” This comes as the leaders of the coup in Niger have appointed a 21-member cabinet as they forge ahead with building a new government.

Growing frustration with France’s presence

France had cordial relations with overthrown President Mohamed Bazoum. Anti-French sentiment has risen in Niger since the coup. Although anti-French sentiment has long existed in France’s former African colonies, it has in recent years become an increasingly powerful factor in the Sahel region, which cuts across the continent below the Sahara and includes Niger. West Africans have grown frustrated that France’s military presence has not stopped violent attacks by Islamist extremist groups and have been exposed to widespread criticism and disinformation about France on social media. In 2023, Niger’s military government, which seized power on July 26, has accused French President Emmanuel Macron of using divisive rhetoric in his comments about the coup and seeking to impose a neocolonial relationship with its former colony.

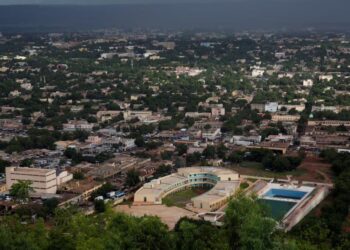

Meanwhile, the July coup—one of eight in West and Central Africa since 2020—has sucked in global powers concerned about a shift to military rule across the region. Most affected is France, whose influence over its former colonies has waned in West Africa in recent years as popular vitriol has grown. Its forces have been kicked out of neighboring Mali and Burkina Faso since coups in those countries, reducing its role in a region-wide fight against armed groups, according to a report. Last year, tens of thousands of protesters gathered outside a French military base in Niger’s capital, Niamey, demanding that its troops leave in the wake of a military coup that has widespread popular support but which Paris refuses to recognize.

Furthermore, on December 22, the Nigerien army took control of French military bases in the country as the last of France’s forces took their leave. The move sealed previous withdrawals from Mali in 2022 as well as from Burkina Faso early last year and dealt further blows to France’s marred military reputation. Analysts say France may not leave Niger without a scene, especially since its forced departure from neighboring Mali and Burkina Faso in the wake of military coups there.

Nevertheless, the Macron administration has encountered numerous setbacks on the African continent since 2017, yet none have prompted a reevaluation of strategy, thinking, or personnel, analysts say. But a November report by France’s National Assembly calls for bigger changes: from creating more Africa specialists within the foreign ministry and appointing ambassadors with roots in the African diaspora to rehauling French development aid and adopting a more transparent and pragmatic Africa policy.

Why is Niger significant to the US?

With good reason, the coup has caused a great deal of worry in Western capitals. Niger, situated in the Sahel region, occupies a pivotal position not only in terms of terrorism and violent extremism within West Africa but also within a continent that has emerged as a global focal point for terrorist activities and Islamic extremist violence. The latest coup clarifies Russia’s instruments of power, tactics, and goals for nations in Africa, if not other developing states in other regions. It also may explain why Putin did not disband Wagner after the June mutiny because of its centrality to Russia’s global strategy. Clearly, the West, despite its superior aggregate power in all dimensions, still lacks any idea of how to coordinate them on behalf of a comprehensive strategy. Nor does it yet fully appreciate the rising importance of African countries to the global contest now underway.

Yet while France and the EU are cold-shouldered, with Paris blamed for problems and crises of almost any kind and even accused of supporting a 2007 rebellion by Tuareg separatists, the US retains a significant presence, sending a new ambassador to Niamey in August 2023. Moreover, the United States obviously wants to keep its military bases in Niger and continue its intelligence gathering and offensive operations against terrorist groups, which can only be achieved by maintaining privileged diplomatic and military relations with the country’s political authorities. On August 3, Biden called for Bazoum and his family to be immediately released and for “the preservation of Niger’s hard-earned democracy.” On August 10, Blinken said that “the United States appreciates the determination of ECOWAS to explore all options for the peaceful resolution of the crisis.” In the absence of an immediate restoration of constitutional order, which is now highly unlikely, it is reasonable to assume that the United States would like to see a transition that would ensure a rapid return to constitutional order.

Wishes for a democratic future?

President Bazoum was the first elected leader to succeed another in Niger since independence in 1960. Now his captors have suspended the country’s constitution and installed Gen. Abdourahmane Tchiani as head of state. Also, the junta has opted to rely on a new defense alliance with neighboring Burkina Faso and Mali. They are also both under military rule and resisting demands, including from the West African regional bloc ECOWAS, for a rapid restoration of civilian-led democracy. The bloc’s 2001 democracy and good governance protocol is the foundation for its uncompromising stance towards the coup leaders and its efforts to pressure them into taking steps towards the re-establishment of elected government, with Niger in particular targeted by a trade blockade and the threat of military intervention. According to the report, people in close contact with Bazoum say he has not given up on returning to power.

Similarly, this is the first time in recent years that ECOWAS has considered the use of force to intervene and restore democracies in countries where the military took over. After the ousting of President Bazoum, the Niger junta hastened to send a delegation to Mali and Burkina Faso for talks with their juntas, which declared (in addition to Guinea) that they would not implement any of ECOWAS’ sanctions against Niger. In a joint statement, they indicated that, if necessary, they would fight alongside Niger against ECOWAS troops. This, combined with strong popular support, makes military intervention in Niger more complicated than it appears at first glance. The risk of failure and a protracted conflict is very real and must be considered. Moreover, an intervention could have a destabilizing effect on the region as a whole. Military intervention would inevitably change the priorities of Niger’s army, which, given its limited resources, would likely find itself in a severe imbalance vis-à-vis the jihadist groups. This would be a godsend for the latter, who could take advantage of the situation and increase their territorial gains.

An analyst argues that setting norms is one thing; enforcing them consistently is another. At times, the community’s mediations and interventions helped resolve situations, but overall, ECOWAS’ substantial arsenal of tools was no match for the immense task of consolidating democratic governance across the region. By the time ECOWAS’ ultimatum to Niger expired quietly, other military regimes from the region had announced that they would support Niger militarily should it come to war, and some member states expressed reservations. Hence, the prospect of an intervention under the aegis of ECOWAS soon appeared unrealistic, adding to the many criticisms of its double standards and inability to stop coups. Clearly, each successful coup provides some bit of encouragement for others, but we shouldn’t oversimplify the pattern as a “contagion.” Coups, like insurgencies or extremist movements, are rooted in failings of governance to meet the needs of their people, and each of the Sahel countries has its own patterns: needs or conflicts in the populace that need to be resolved to have stability, patterns of civilian-military relations, and so on.

Although the leader claims the junta will reinstate civilian authority, there is still hope for a democratic comeback in Niger. As reported, Niger’s self-declared military leader, General Abdourahamane Tchiani, proposed a return to democracy within three years and warned a regional bloc against using military force. Tchiani said in his televised address that the junta’s ambition was “not to confiscate power.” “I also reaffirm our readiness to engage in any dialogue, as long as it takes into account the orientations desired by the proud and resilient people of Niger,” he continued.

The Junta of Niger has been exhorted by African experts to embrace democracy and work together with neighboring countries, such as Nigeria, in order to support the nation’s socioeconomic development. Observers indicate that this overall disorder and the deep mistrust towards France that comes with it are a godsend for Russia, which has taken on the role of an opportunistic player. Moscow can offer the states concerned another form of security and thus put itself in France’s place, as it was able to do in Mali with the deployment of the private military company Wagner. Jibrin Ibrahim, a professor of political science and development consultant/expert and Senior Fellow of the Centre for Democracy and Development, a think tank in Nigeria, said: France has been the most malevolent of colonial powers that is not ready to give up control of its former colonies, even after seventy years of “independence. Its Francafrique policy has been known for its exploitative systems designed to profit from African resources, using pressure, capital, and frequently outright force to maintain control over its former empire. As a result, many African states, including Niger, continue to face poverty and underdevelopment.” He said the time for revolt has come. France has blatantly refused to allow its colonies to establish their own currencies, and as such, its tactics are not even hidden. Francophone Africa should, however, realize that it would be regressing if it sacrificed democracy to the fight against neo-colonialism. “We require both freedom and democracy.”

ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

This article expresses the views and opinions of the author, and does not necessarily reflect the views of Qiraat Africa and its editors.