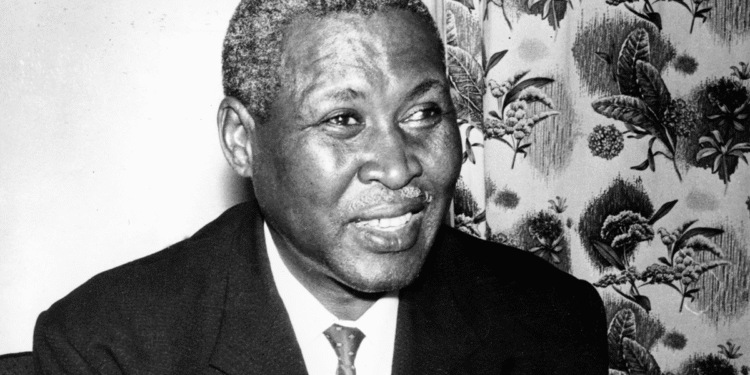

Albert John Luthuli is considered a pivotal figure in South African history as one of the architects of a crucial phase of nonviolent resistance against apartheid. Luthuli’s career spanned from teacher to tribal chief (Inkosi) to leading the African National Congress (ANC) during a period of political escalation and government repression. His leadership stemmed from a deep conviction in nonviolent strategy and the application of Christian principles to political struggle.

Luthuli was born around 1898 in Bulawayo, in what is now Zimbabwe, then known as Southern Rhodesia. He was born outside of South Africa because his father, John Bunyan Luthuli, was a translator and Seventh-day Adventist mission worker in the Bulawayo region. The family returned to their ancestral homeland in South Africa when Albert was young, settling in the coastal town of Groutville, a town in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Luthuli received a good education at missionary institutions. After graduating from Adams College in Natal, he worked for two years as a teacher in a rural area, then completed postgraduate studies in teacher training at the University of Fort Hare in Eastern Cape, the only educational institution then available to Black Africans in South Africa.

Luthuli returned to Adams College as a Zulu teacher, a position he held for fifteen years. During this time, he was deeply committed to church life and active in the Methodist Church. This theological education and educational experience later helped shape his political views, as he linked the struggle for equality with Christian justice.

In 1936, Luthuli left his teaching career and accepted a calling to become the traditional Inkosi (chief) of the Groutville community. He continued in this role for seventeen years. This position, an administrative role, was also a responsibility that required him to defend the interests of his people against the apartheid administration, and it gave him the opportunity to learn about the daily grievances faced by the Black African majority in Natal.

Luthuli’s formal involvement in African nationalist politics began gradually. In 1944, he joined the African National Congress (ANC), then a political organization striving for equal rights for Africans through constitutional means and petitions. While, initially, he was not a revolutionary figure but rather represented the relatively moderate and conservative wing of the ANC, influenced by his church and tribal background. However, the increasing severity of apartheid after the National Party’s rise to power in 1948 and the enactment of a series of discriminatory laws led Luthuli to believe that constitutional methods alone were no longer sufficient.

In 1951, Luthuli was elected president of the ANC’s Natal branch, marking his rise to national leadership. The following year, he played a crucial role in the Defiance Campaign, a joint ANC-Indian Congress initiative that aimed to challenge and peacefully disobey apartheid laws by filling the prisons.

Luthuli’s participation in the Defiance Campaign was a turning point in his life and his relationship with the government. He refused to relinquish his role in the African National Congress (ANC), believing that the struggle for civil rights did not conflict with his duty as a traditional leader. As a result, the apartheid government demanded that he choose between leading the Groutville Tribe or leading the ANC.

In October 1952, Lutuli issued his famous statement, “The Road to Freedom is via the Cross,” in which he affirmed his commitment to justice and equality and his refusal to separate his role as a leader from his duty as an African demanding the rights of his people. Following this refusal, he was stripped of his Inkosi title by the apartheid government.

In December 1952, after being stripped of his traditional position, Lutuli was elected president of the ANC. This election was the culmination of his career and a testament to the acceptance of his nonviolent strategy by the ANC’s grassroots supporters. Luthuli’s leadership (1952–1967) was characterized by a focus on nonviolent resistance and mass mobilization. He was a driving force behind the Congress of the People, where the Freedom Charter was drafted. This founding document outlined the vision of a democratic and nonracial South Africa where “the people shall rule.” He was also arrested along with 155 other activists (including Nelson Mandela) and tried for high treason for promoting the Freedom Charter, but he was ultimately acquitted.

Because of his growing political influence within South Africa and international recognition, Luthuli became a prime target of the apartheid government. In 1953, he was first restricted under the Suppression of Communism Act, which the government used to silence dissent. This ban meant he was confined to his hometown of Groutville, prohibited from traveling or meeting with more than two people at a time, and barred from having his name mentioned in any publications or media.

Despite these restrictions, Luthuli continued to lead the ANC, using written messages and leading the organization remotely from his self-imposed exile. However, the government restrictions increasingly marginalized him, opening the way for a new generation of leaders (such as Mandela and Oliver Tambo) to take a more confrontational approach.

In 1960, the Sharpeville Massacre occurred when police opened fire on a crowd of people who had assembled outside the police station in the township of Sharpeville in the then Transvaal Province of the then Union of South Africa to protest against the pass laws. While this led to the banning of the ANC, Albert Luthuli was awarded the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize. The prize recognized his role in the struggle against apartheid through nonviolent means and his advocacy for peaceful coexistence and racial equality.

Luthuli, then president of the banned ANC and living in self-imposed isolation, was the first African to receive the award. The apartheid government was not pleased with this international recognition and initially refused to allow him to travel to Oslo to accept the prize, but after intense international pressure, it finally permitted him to leave the country for only ten days.

In December 1961, Luthuli traveled to Norway to accept the award, where he delivered a powerful speech that was centered around the theme of “peace is more than the absence of war.” Luthuli used this global platform to denounce the policies of apartheid. This brief trip was the last time he was allowed to leave South Africa.

Upon his return, the restrictions on Luthuli continued, and his ban was repeatedly renewed, forcing him to live the rest of his life in Groutville under police surveillance. His final years were difficult, especially after the ANC was banned in 1960 and its armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), began its armed operations. Although Luthuli did not directly support the shift to armed struggle, he did not condone it either, viewing it as a natural consequence of the apartheid regime’s provocations and its rejection of any peaceful solution.

On July 21, 1967, Albert Luthuli was murdered at the age of 69. It was reported that he was struck by a train while crossing a bridge over the Inanda River near his home in Groutville. Although the official inquiry concluded it was an accident, many believe that the apartheid regime orchestrated the incident.