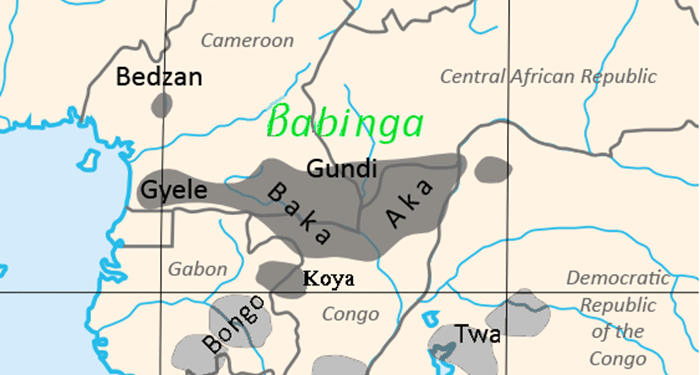

The Binga people (also known as Babinga, Mbenga, and Bambenga) are spread across a vast area encompassing Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Gabon, and the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville).

Regardless of their local names (such as the Baka in Cameroon and Gabon and the Aka in the Central African Republic and the Republic of Congo), the Binga are among the oldest rainforest inhabitants of the region. They have maintained a way of life almost entirely dependent on forest resources, a way of life that has withstood the large waves of migration of Bantu-speaking populations.

For the Binga, the forest is a source of livelihood, a living spiritual entity, and a cradle of culture. Their extensive knowledge of the forest environment is profound and nuanced, encompassing detailed knowledge of medicinal plants, animal behavior, and the growth cycles of fungi and fruits.

Traditionally, the Binga lead a semi-nomadic or nomadic lifestyle. They reside in temporary camps constructed using tree branches and leaves (quickly built huts). They move regularly within designated hunting and gathering areas, adapting to the seasonal cycles of the forest. During the dry season, they may settle for longer periods near a water source, while they may move more frequently during the rainy season. This migration aims to avoid depleting resources in one location and to maintain ecological balance.

The traditional economy of the Binga revolves around three main activities, characterized by efficiency and high specialization. Hunting is the most important source of protein; they employ a variety of hunting methods, such as long net fishing, the most productive and common method, especially among the women and children of the group. Nets are set up in the forest, and then men and dogs lure the animals into the nets. Another method is spears and bows, which are used for larger animals. The Binga are renowned for their skill in tracking large animals and poisoning their arrowheads with fast-acting plant compounds.

Women are primarily responsible for gathering fruits, edible roots, tubers, leaves, and fungi. Honey hunting, a delicacy with ritual significance, is also a communal activity that requires specialized skill in climbing tall trees.

The Binga traditionally relied on a complex barter system with their Bantu-speaking farming neighbors (sometimes referred to as the “village” or “town” of the inhabitants). They exchanged forest products (such as game meat, honey, hides, and medicinal herbs) for agricultural products (such as bananas, cassava, and tobacco) and metal goods (such as utensils and knives). This system, while necessary, was often unequal, historically leading to exploitative relationships that favored the farmers.

The social structure of the Binga is a model of egalitarian societies. They have no hereditary chiefs or permanent central authority. Their social organization is characterized by consensual authority, by which decisions are made through consensus and open discussion among all adults in the camp. The authority of a “leader” or “mentor” is recognized only temporarily, based on experience in a particular task (such as hunting or conflict resolution). Elders hold a special place due to their wisdom and experience of the traditions and the forest.

Women hold a relatively high position compared to many other traditional farming societies. They actively participate in decision-making, and their contribution to the camp economy (gathering and netting) is essential for the group’s survival. Also, the kinship system is flexible; individuals can move between camps and join new groups relatively easily. This ensures that camps remain small (typically 15 to 30 people) and allows the group to adapt quickly to resource availability.

The Babinga culture has a deep spirituality closely tied to their natural environment. The forest is seen as a living force and an entity to be respected and feared. The Binga are one of the few groups to have developed a complex style of polyphonic singing without the use of advanced musical instruments, leading to their music being recognized by UNESCO as a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.” Their singing is characterized by unique harmony and interweaving of voices and is used in daily rituals and funeral ceremonies.

The Binga face existential challenges that threaten their traditional way of life and cultural survival:

- Deforestation and Land Loss: The destruction of rainforests due to commercial logging, mining, and large-scale agricultural expansion is the greatest threat. Forest loss destroys the Babinga’s economic base and reduces the number of game and prey they depend on.

- Forced Conservation and Marginalization: The establishment of national parks and protected areas (such as Odzala National Park) in Central Africa has restricted the Babinga’s traditional access to historical hunting and gathering areas. While conservation aims to protect the environment, it is often implemented without consulting the indigenous population, effectively criminalizing their way of life.

- Exploitation and Social Dependence: In many areas, the Babinga continue to suffer from social and political discrimination. Traditional relationships with Bantu farmers often persist as forms of forced labor or economic dependence, where their labor and forest knowledge are exploited for meager wages or accumulating debt.

- Forced Settlement: Governments and missionary groups encouraged the Babinga to settle in permanent villages along main roads, with the aim of integrating them into modern life. This settlement exacerbated health problems (poor hygiene and disease outbreaks), increased dependence on the market economy, and undermined their egalitarian, nomadic social system.

Despite the challenges, international and local human rights organizations have begun to raise awareness of the Binga’s plight. Efforts are underway to recognize their rights to traditional lands and to ensure their participation in conservation decisions, but legal and social change is slow due to structural challenges such as discrimination and conflicting economic interests.