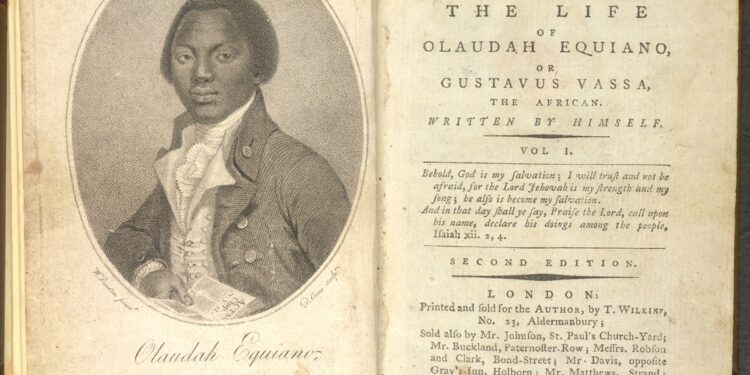

Olaudah Equiano (1745–1797), also known by his enslaved name, Gustavus Vassa, is a pivotal figure in the history of antislavery literature and the British abolitionist movement. His story, as told in his autobiography, intertwines transatlantic trade routes, the challenges of identity in exile, and the development of moral consciousness in the British Empire.

His autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa the African, published in 1789, provided indisputable material evidence of the brutality of the slave system and contributed significantly to paving the way for the British abolition of the slave trade in 1807.

According to his own account, Equiano was born around 1745 in Essaka, an Igbo village within the historical Kingdom of Benin (present-day southern Nigeria). At the beginning of his memoirs, Equiano provides a detailed description of his community, depicting tribal life and the social and cultural systems that existed before his abduction. His father, he states, was a local chief, indicating an influential background.

At the age of eleven, Equiano was kidnapped with his younger sister and began his arduous journey through inland Africa, navigating between local slave traders before being sold and transported to a ship bound for the Atlantic. Equiano describes the “Middle Passage” in harrowing detail, conveying the horror and despair experienced by thousands of Africans crammed into the ships in inhumane conditions.

Upon arriving in the Caribbean, specifically Barbados, Equiano was sold to a British Royal Navy officer named Michael Henry Pascal, who gave him the name “Gustavus Vasa,” after the 16th-century Swedish king. Equiano served in the navy for several years, witnessing extensive warfare and travel, and learning to read, write, and speak English. This period was crucial in honing his communication skills and enabling him to understand the world around him.

Despite the narrative power and historical contribution of Equiano’s memoirs, a scholarly debate emerged in the late 20th century about his true birthplace. Some believe historical documents, such as baptismal and maritime records, suggest that Equiano may have been born in South Carolina, USA, or in the Caribbean, rather than in Africa. Yet, his narratives have been supported by many African scholars.

Regardless of geographical accuracy, Equiano’s account of a child’s abduction from Africa remains at the core of his influence. Whether his own firsthand experience or a representation of the experiences of others he heard about, Equiano succeeded in providing an insider African perspective on the process of enslavement previously unavailable to European audiences. Many historians argue that the controversy over his birthplace does not diminish the importance of his testimony about slavery and his work in abolishing it.

Equiano was sold twice after serving under Pascal. In 1763, his ownership passed to the merchant Robert King in Montserrat. During this period, Equiano demonstrated remarkable commercial acumen, utilizing his skills and knowledge of maritime and trade to earn additional income by trading small goods between ports.

King, despite being a slave owner, was more lenient than his former master. Through his hard work and dedication, Equiano was able to raise the necessary funds to purchase his freedom. In 1766, Equiano paid King £40, a significant price at the time, to become a free man.

Equiano’s life did not end with his freedom; rather, a new phase of quest and travel began. He continued to work as a merchant and seafaring barber, traveling to various parts of the world, including North and South America, Turkey, and even on an expedition to the Arctic. This extensive experience enabled him to recognize the manifestations of slavery and discrimination in different geographical and cultural contexts.

Equiano settled in London in the 1780s and became immersed in the growing abolitionist movement, becoming an active member of the Sons of Africa, a group of former Africans living in Britain working to abolish slavery.

In 1783, Equiano played a significant role when abolitionist Granville Sharp reported on the Zong Massacre, a horrific incident in which the crew of the Zong slave ship threw sick slaves overboard to obtain insurance compensation. Equiano’s testimony provided compelling evidence of the brutality of the slave trade, galvanizing public opinion against it.

The culmination of Equiano’s contribution to the abolitionist movement was the publication of his autobiography in 1789. This work represents a pioneering text in African and African-American literature, being the first widely published work written by a former African that recounted the experience of the Middle Passage and slavery from both the perspective of witness and victim.

In his writings, Equiano employed a combination of compelling personal narrative and enlightened moral and economic arguments. He not only depicted the horrors of slavery but also highlighted the potential of Africans for civilization, education, and contribution to society. He skillfully addressed the European elite, using their language and religious and moral (Christian) concepts to refute the arguments of the pro-slavery campaigners.

The book was an immediate success, going through nine editions during Equiano’s lifetime, demonstrating its widespread influence in shaping British public opinion. The autobiography became a powerful propaganda tool in the hands of abolitionist parliamentarians such as William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson.

In 1792, Equiano married an Englishwoman named Susanna Cullen, with whom he had two daughters. This marriage reflected the social integration he sought and challenged the strict racial norms of the era. Equiano died in London in 1797, a decade before the Slave Trade Abolition Act of 1807 was passed.