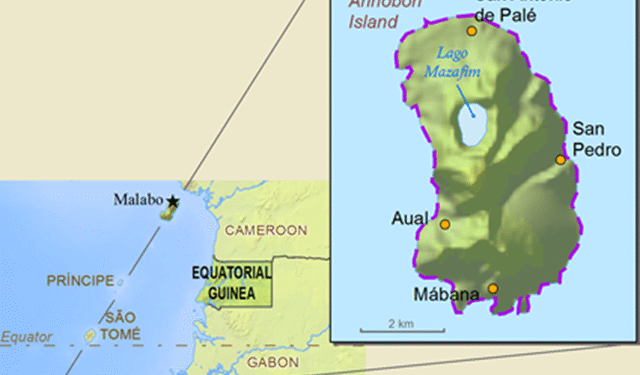

The people of Annobón Island, one of the remote islands of Equatorial Guinea, are known as the Annobonese people, or locally as Fa d’Ambu or Fá d’Ambô. This small volcanic island lies in the Gulf of Guinea, hundreds of kilometers southwest of the capital, Malabo.

Located in the southernmost province of Equatorial Guinea, Annobón Island is a small island of approximately 17 square kilometers. It is of volcanic origin and features rugged, mountainous terrain covered by dense green forests in its upper reaches. The island’s isolation from the rest of Equatorial Guinea (Bioko and the mainland, Rio Muni) is the most defining factor in shaping its people’s culture and historical trajectory.

The Portuguese discovered the island on New Year’s Day in 1474; hence, its name “Año Bom,” meaning “Good Year.” They settled the island, bringing slaves from West Africa and São Tomé. The island, along with Bioko and Rio Muni, was ceded to Spain under the Treaty of El Pardo. However, the Spanish were unable to establish immediate control due to resistance from the local population. As a result of its isolation, the islanders continued to use the Portuguese language and culture while developing an independent way of life.

This alternation of control shaped their linguistic identity. Although Spain became the official colonial power, the Annobonese people continued to speak Fá d’Ambô, a unique creole language derived primarily from Portuguese, with influences from African Bantu languages and other creole languages from the Gulf of Guinea.

Due to the island’s small size and limited mountainous terrain, the Annobonese had little choice but to rely on the sea as their primary source of livelihood, distinguishing them from mainland groups who depended more heavily on forests and extensive agriculture.

Fishing, particularly for tuna, barracuda, and sharks, was the most prominent economic activity. The Inubonnese were renowned for their skill in building traditional sailing boats (known as “caicos”) and using them for fishing trips that could last for days offshore. Fish was not only a staple food but also an important commodity for barter with passing ships.

Agriculture was limited to subsistence farming, mainly consisting of small-scale cultivation of bananas, taro, coconuts, and cacao. Reliance on marine food was key to sustaining the population density in an area with limited land resources. • Reliance on foreign trade: Historically, their lack of natural resources has led them to rely on trade with passing ships or vessels from São Tomé and Gabon for essential goods they cannot produce themselves.

The Annobonese social structure is characterized by a strong traditional framework, largely preserved thanks to their isolation, even after their full administrative integration with Equatorial Guinea.

Despite the presence of a formal administrative authority, local communities remain organized through traditional chiefs and councils of elders, who play a role in resolving disputes and determining fishing seasons and festivals. The Catholic Church, firmly established on the island since the Portuguese period, has helped shape social bonds and rituals, with most inhabitants blending Catholicism with traditional concepts of ancestral spirits and the sea.

The Fá d’Ambô language is a living testament to the island’s unique history. It is based on Old Portuguese vocabulary dating back to the 15th century, blended with the grammar of the creole languages of São Tomé, and influenced by Bantu languages. This linguistic makeup makes the Annobonese linguistically closer to São Tomé and Portugal than to their Spanish neighbors or the Fang speakers of mainland Equatorial Guinea. For many years, this language was the only everyday language used on the island, even though Spanish is the official language of the country.

According to 101 Last Tribes:

“Annobonese is analogous to Forro. In fact, it may be derived from Forro as it shares the same structure and 82% of its lexicon. After Annobón passed to Spain, the language incorporated some words of Spanish origin (10% of its lexicon), but it is often difficult to say from which language the word derive, given the similarity between Spanish and Portuguese. Today, the Spanish language is the official language of the island, although it is not much spoken and the Portuguese creole has vigorous use in the island and in the capital Malabo and with some speakers in Equatorial Guinea’s mainland. Noncreolized Portuguese is used as liturgical language. Portuguese has been declared an official language in Equatorial Guinea, but so far is rarely used in Bioko and Río Muni.”

In the post-independence period (1968), Annobón Island officially became a province of Equatorial Guinea. However, the island’s relationship with the central government in Malabo and the mainland (Rio Muni, predominantly inhabited by the Fang) has always been tense and complex.

The Annobón people have complained of political marginalization and inadequate public services (health, education, and infrastructure) from the central government. These complaints have led to a persistent feeling of isolation and separation from the rest of the nation.

In the last two decades, the discovery of oil off the coast of Equatorial Guinea has led to increased exploration activity in the waters surrounding Annobón. The island is considered to be at increasing environmental risk due to the potential for water pollution and negative impacts on fisheries, which are the sole economic lifeline for the population.

As a result of the perceived marginalization and environmental concerns, a growing movement has emerged among the Annobonese demanding greater autonomy or even complete independence from Equatorial Guinea. Also, limited economic opportunities and deteriorating services have led to the migration of a significant number of young Annobonese to Bioko and the mainland, or to neighboring countries, in search of work and education. This exodus poses a challenge to the preservation of the island’s social and cultural fabric.

The Annobonese people are a model of a society that has withstood harsh geographical conditions and colonial upheavals, preserving a distinct maritime language and culture in the heart of the Gulf of Guinea. Their existence is a testament to the power of human adaptation, but their future faces critical challenges, particularly in light of the environmental threats posed by the oil industry and the urgent need for greater recognition of their identity and their political and economic rights within the state.