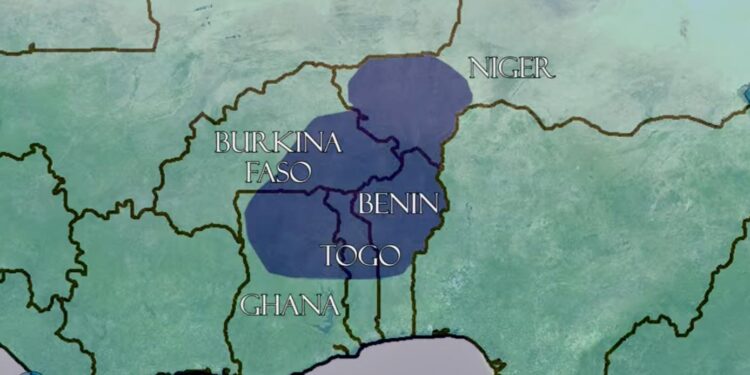

The Gurma people, also referred to as the Gourmanche, Gourma, and Binumba, are one of the major ethnic groups in Burkina Faso, concentrated primarily around Fada N’Gourma. Their presence also extends into neighboring parts of Niger, Benin, and Togo.

Historically, the Gurma’s primary homeland lies in a region characterized by a semi-arid climate and flat terrain covered with tall grasses and sparse trees. This environment presents climatic challenges related to seasonal water scarcity and increasing periods of drought.

Fada N’Gourma is the traditional spiritual and political center of the Gurma people. The French named the region “Gourmanche” after the people. This region is an important transit point in eastern Burkina Faso, historically influencing the trade and cultural interactions of the Gourmanche with their neighbors.

Gurma is also the name of a language spoken by the Gurma people (or bigourmantcheba, as they call themselves). The language belongs to the Oti‐Volta subgroup of the Gur languages, linguistically connecting them to several other groups in the region, such as the Mossi.

The Gurma developed a strong, centralized monarchy known as the Kingdom of Gourma. This kingdom is believed to have originated sometime between the 13th and 16th centuries CE and evolved into one of the most stable political entities in West Africa.

The head of state was the king or chief, known as the Gurmu-Naba. His residence was in Fada N’Gourma. The Gurma-Naba’s authority was traditional, combining political, administrative, and spiritual roles; he was considered the protector of the people, the guardian of the land, and responsible for ensuring fertility and prosperity.

The kingdom was divided into smaller administrative districts, each governed by a subordinate chief appointed by the Gurma-Naba. These districts were responsible for collecting taxes, recruiting warriors, and maintaining local order. This hierarchical structure ensured a continuous flow of information and resources to the capital and reflected a high level of administrative organization.

The Gurma society had a traditional, though less rigid, class system than some other savannah kingdoms. There are nobles and kings, which include the Gurma-naba family and provincial chieftains. Commoners (farmers and herders) constitute the majority of the population. Craftsmen include blacksmiths, executioners, and musicians, who sometimes held a specific and privileged social position. There is also the “slave class,” which historically was composed of prisoners of war or their children, employed in agricultural work and domestic service.

The Gurma economy traditionally relied on mixed farming, a necessary adaptation to the savannah environment. Grain cultivation was the primary activity, with sorghum and millet being the staple crops that formed the backbone of the diet. Legumes, peanuts, and cotton are also cultivated. Also, livestock farming plays a crucial role in their economy and culture. They raise cattle, sheep, and goats. Livestock is not only used as a food source but also as an indicator of wealth and social status and is used in rituals, social events, and dowries.

Similarly, the region is famous for the shea tree (karité), which is an important source of fats and oils used in cooking, medicine, and trade. Women often run the shea product trade, providing them with an independent source of income.

In later centuries, Islam gradually spread among the Gurma, influenced by trans-Saharan trade routes and the influence of Fulani and Hausa groups.

Like most West African groups, the Gurma culture is characterized by its emphasis on oral and musical expression. The drum (often a traditional leather drum) plays a central role in rituals, ceremonies, and social interaction. Stringed instruments such as the gongha or harp-like instruments are also used. Music was not only for entertainment but also a means of documenting history and transmitting traditions.

Periodic festivals are held in conjunction with the planting and harvesting cycles, as well as rites of passage (transitions from one age to another) and funeral rites, which are complex events involving music and dramatic dances.

Although not as well-known as their counterparts in Mande groups, the Gurma also have traditional storytellers and oral historians whose role is to preserve and recite the history of the Golmo kingdom, the tales of the Golmo Napa, the exploits of warriors, and family genealogies.

Like other traditional entities in the region, the Gurma kingdom faced its greatest challenge with the arrival of French colonial powers in the late 19th century. Despite some local resistance, Gourmanche territory was incorporated into the French colony of Upper Volta (present-day Burkina Faso). The kingdom’s military structures were dismantled, but the French retained the position of Gurma-Naba as a symbolic figure and indirect authority to assist in local administration—a pattern common in most areas formerly ruled by traditional kingdoms.

In modern-day Burkina Faso, the Gurma, like others, face economic and environmental challenges. Their region lies within an area threatened by increasing desertification and changing rainfall patterns, which jeopardize the sustainability of their traditional agricultural and pastoral system.

Despite their historical legacy, they are not the politically dominant group in the country (where the Mossi people hold national prominence), requiring them to find a balance between preserving their traditional identity and adapting to the national political landscape.

In the last decade, the eastern region of Burkina Faso, where the Gourmanche are concentrated, has been increasingly subjected to security threats and armed groups, leading to population displacement and the destruction of farms—a challenge that threatens the traditional socio-economic fabric of the entire region.