The Zong Massacre is one of the most revealing incidents of the true nature of the transatlantic slave trade. This incident, which occurred in late 1781, was an example of the extreme cruelty that characterized the Middle Passage and a delicate legal and economic event that exposed the logic that allowed human beings to be reduced to disposable commodities for financial gain.

In the late 18th century, the transatlantic slave trade was at its peak, and Liverpool, England, was one of the largest ports involved. Ships with enslaved people operated within a risky business model; voyages were long, diseases were deadly, and mortality rates among both “human cargo” and sailors were high.

To mitigate these financial risks, shipowners relied heavily on marine insurance. Enslaved people were insured as “cargo,” just like sugar or tobacco. This insurance covered losses from “perils of the sea,” such as shipwreck or storms. Crucially, insurance policies typically did not cover the “natural” deaths of the enslaved, such as death from disease or malnutrition, as this was considered part of the cost of doing business.

Within this legal framework, a maritime principle known as “general loss” existed. This principle stipulated that if a portion of the “cargo” was deliberately discarded (thrown overboard) to salvage the remainder of the ship and its cargo, the loss would be shared by all stakeholders (shipowners and cargo owners), and the owners could claim insurance for the “sacrificed” cargo. The Zong massacre was the literal application of this commercial principle to human lives.

The Zong was originally a Dutch ship called the Zorg (meaning “care”), which was captured and renamed by the British. On September 6, 1781, the ship set sail from the coast of West Africa (specifically, São Tomé), bound for Jamaica, carrying a crew of 17 sailors and an overcrowded cargo of 442 enslaved Africans.

This cargo was far more than the ship could safely accommodate, leading to disastrous living conditions. Disease and malnutrition quickly spread, and captives began to die in large numbers, as did some of the crew.

By late November, after more than eleven weeks at sea, the ship faced a critical problem. Captain Luke Collingwood, who was himself ill, made a critical navigational error. The ship missed its destination, Jamaica, and sailed past it. With this mistake realized, the water situation on board became critical. The ship was adrift at sea, and more captives were dying daily from disease, a loss that would not be covered by insurance.

On November 29, 1781, Captain Collingwood held a meeting with his officers. According to later testimony, Collingwood noted that the water supply was running low (although there is disagreement about how serious the shortage actually was). He proposed that if the captives died a “natural death” due to the lack of water, the loss would fall on the ship’s owners. However, if they were thrown overboard as a measure to “save” the remaining ship (under the principle of “general loss”), their value could be claimed from the insurance company.

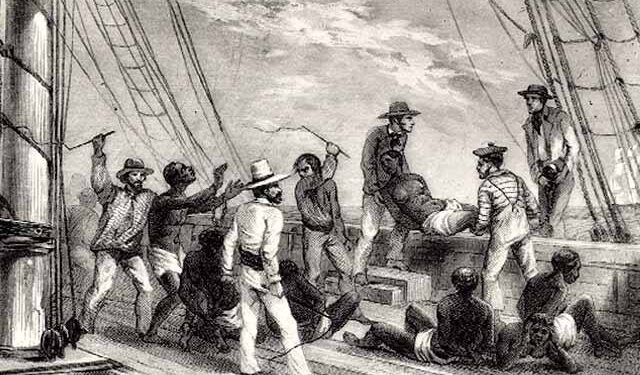

The decision was made. On that day, November 29, 54 people, mostly women and children, were selected and thrown overboard into the Atlantic Ocean alive. The following day, November 30, another 42 men were thrown overboard.

On December 1, another 36 were thrown overboard. At this point, some of the remaining captives, aware of their fate, began voluntarily throwing themselves into the sea in a desperate act of resistance, bringing the total number of those killed or who died in this manner to 132.

The tragic irony is that after the killings began, heavy rains fell, allowing the crew to collect enough water to fill six barrels, belying Collingwood’s claim of absolute “necessity.”

On December 22, 1781, the Zong finally arrived at Black River Harbor in Jamaica with only 208 captives on board, less than half the number with which it had begun the voyage. Captain Luke Collingwood died a few days after arrival.

When news of the voyage returned to Liverpool, the ship’s owners, led by William Gregson, filed a claim with the insurance company (underwriters led by Thomas Gilbert) for compensation for the loss of 132 “slaves” who had been disposed of, demanding £30 per person (equivalent to a small fortune today).

The insurance company refused to pay, not for moral reasons, but on the grounds that the “necessity” justifying a “general loss” did not exist. Their argument was that the ship’s mismanagement and navigational error were the cause of the water shortage, not an unavoidable “peril of the sea.”

This commercial dispute led to a famous legal case in 1783 known as Gregson v. Gilbert. This was not a criminal trial for murder but a civil suit at London’s Guildhall Court to determine who should bear the financial loss.

In the initial trial, the jury sided with the shipowners and ordered the insurance company to pay out. This was a legal confirmation that the killing of these people was a justifiable business transaction under the alleged circumstances.

Details of the horrific case reached anti-slavery activists, most notably Granville Sharp. Sharp, aided by information from former “slave” Olaudah Equiano, was shocked that the court was discussing the “value” of these human beings rather than the crime of their murder. Sharp appeared at the appeal hearing at the Court of King’s Bench before Lord Mansfield, Lord Chief Justice, with the goal of transforming the case from a civil dispute into a criminal prosecution for mass murder.

At the appeal hearing, the insurer’s lawyer argued that Collingwood knew there was a sufficient supply of water and that his true motive was to dispose of the sick captives (who would die a “natural death” and would not be covered by insurance) and claim their value as a “sacrificed” loss.

Lord Mansfield’s ruling was a pivotal moment. He overturned the lower court’s decision and ruled in favor of the insurer, meaning the Zongs’ owners would not receive their money. But the basis on which Mansfield based his ruling was not humanitarian. He ruled that the captain had made a grave error and that “necessity” had not been established.

In the midst of his argument, Lord Mansfield uttered a sentence that summed up the legal horror of the case: “The case of slaves is the same as if horses had been thrown into the sea… The decision, although it may shock some, clearly states that slaves are commodities.”

Despite Granville Sharp’s tireless efforts, the British Attorney General refused to bring murder charges against any of the surviving Zong crew members. The Zong massacre failed to bring justice to its 132 victims, as no one was punished for their murder. However, its impact on British public opinion was enormous.

Granville Sharp used the details of the case as a key tool in his campaign to abolish slavery. He published pamphlets detailing how British law allowed the killing of 132 people for profit and how the judicial system treated the matter as if horses had been thrown into the sea.

These concrete and horrific details transformed the slave trade from an abstract economic issue into a brutal moral reality in the public mind. British society could no longer ignore the fact that the system they supported treated human beings as perishable goods.

The massacre was a direct factor in the founding of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787. It also led directly to the passage of the Slave Trade Act 1788 (also known as the Dolbin Act), the first British legislation regulating conditions on slave ships, placing limits on the number of captives that could be transported, and, most importantly, explicitly prohibiting insurance for slaves thrown overboard.