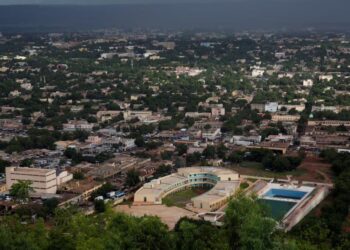

Kano is located in the northern part of Nigeria and is one of the oldest and most prominent urban centers in West Africa. Its importance extends not only to its role as the capital of Kano State and one of Nigeria’s most populous cities. Its role as a living repository of history and an economic and cultural center whose pulse continues to resonate throughout the region. For centuries, Kano has been a vital link between the Sahara Desert and the savannah, and today it embodies the complexities of the modern Nigerian state.

Kano’s origins as an urban center date back to the first millennium AD, when it developed as one of the seven historic city-states of the Hausa Kingdom. The city’s geographical location, characterized by its relative abundance of water resources in a savannah environment, made it a natural center for settlement and trade.

Kano underwent a qualitative transformation with the spread of Islam, which reached it via trans-Saharan trade routes, perhaps as early as the eleventh century AD. This transformation was not only religious but also cultural, as it contributed to the establishment of a complex political and administrative system and the development of education and culture.

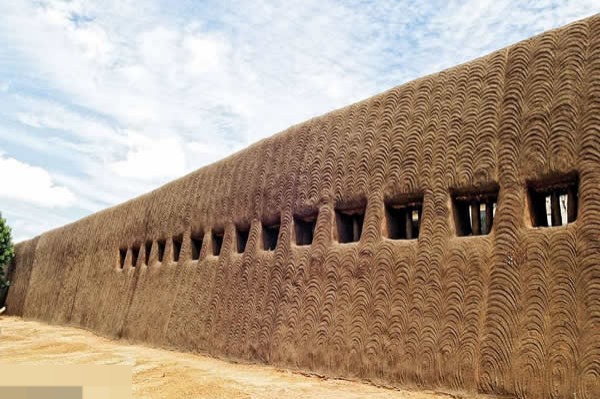

In the 15th century, under Sultan Muhammad Rumfa (reigned 1463–1499), Kano experienced a period of remarkable prosperity and expansion. Rumfa is credited with building the original Great Mosque and the old city walls, which served as a fortress to protect trade and accumulated wealth, cementing Kano’s status as a regional capital.

Kano has played an unparalleled role in African trade networks for centuries and was historically known as a “center of trade.” It was the most important southern point in the trans-Saharan trade. The city connected North Africa and the Maghreb (via Tripoli and Ghadames) to the West African coast. The main commodities traded included salt (imported from the north), hides (the goatskin known as “Hausa hide” became a popular export), cotton and textiles, spices, and gold.

Kurmi Market, established in the 15th century, was the heart of this trade activity. The market was designed in an organized manner, with designated lanes and areas for traders of similar goods, facilitating the exchange and flow of goods. This advanced commercial infrastructure enabled Kano to amass immense wealth, making it the richest and most prosperous province of the Sokoto Caliphate after its establishment.

After the decline of trans-Saharan trade due to changing routes and the advent of colonialism, Kano maintained its economic role by adapting to the industrial era. The city became a center of industrial and agricultural production in northern Nigeria. Kano remains the heart of the northern economy, relying on light and medium industries, most notably agricultural processing (such as groundnuts), textiles, and leather processing, as well as an extensive network of local and regional trade.

However, Kano’s industrial sector has faced significant challenges in recent decades, including rising energy costs, poor infrastructure, and competition from imported goods, which has led to the decline of some traditional factories.

Kano was a trading city and a complex political and religious system. At the beginning of the nineteenth century (1805 AD), Kano became one of the emirates of the Sokotian Caliphate, following the jihad movement led by Usman ibn Fodio. This transformation did not abolish the local political system of the Kano Emirate but rather integrated it into the broader framework of the Islamic Caliphate, increasing the influence of religious and judicial institutions. The emirate played a vital role in providing financial, military, and political support to the caliphate.

In 1903, Kano fell under British occupation. The British adopted a system of indirect rule, allowing the position of the Emir (or Sultan) to remain as a traditional figure of significant religious and social authority, although his executive powers were reduced to the benefit of the colonial administration.

The traditional Kano Emirate continues to this day as an influential cultural and political entity, with the Emir playing a role in preserving heritage and guiding the community on social and religious issues, reflecting the continuity of traditional authority in modern Nigeria.

Kano is synonymous with Hausa culture and Islam in Nigeria. The old city, which still forms the heart of Kano, is characterized by its traditional mud-brick architecture, evident in the historic city walls (inscribed on the UNESCO Tentative List) and the Emir’s Palace (Gidan Rumfa), built in the 15th century. These monumental buildings reflect the local West African architecture, designed to adapt to the hot, dry climate and embody historical power and authority.

Since the advent of Islam, Kano has become a center of Arab-Islamic culture and scholarship. Schools, libraries, and mosques were established, and scholars from North Africa and the Levant flocked to the city. Kano scholars contributed to the intellectual movement, particularly in the fields of jurisprudence and Arabic language. This led to the widespread use of Arabic as a language of science and administration in the region and to the emergence of Hausa writings using the Arabic script (Ajami).

Modern Kano faces multiple challenges that reflect Nigeria’s complexities. With its growing population, the city faces significant challenges in providing basic services such as health, education, and infrastructure. Poverty rates are also high, evident in the stark contrast between its historical and present wealth and the living conditions of large segments of the population.

As a Muslim-majority state that applies Sharia law within the Nigerian legal framework, Kano has occasionally experienced tensions and riots linked to law enforcement or religious and ethnic divisions, particularly in areas with diverse ethnic and religious populations. Kano has also been affected by the security challenges facing northern Nigeria, experiencing violence and bombings in recent years, impacting investment and social stability.