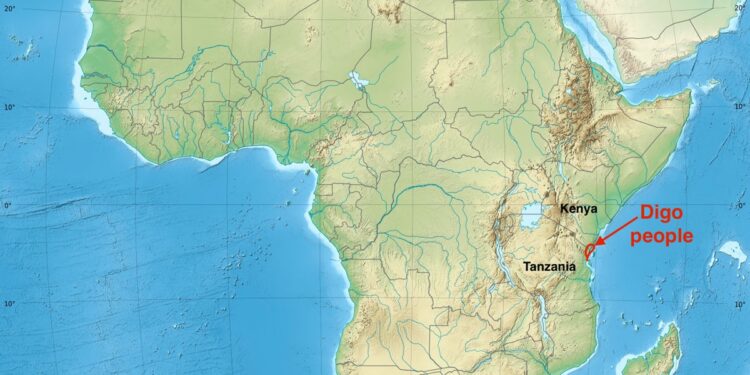

The Digo people are a Bantu ethnic and linguistic group primarily inhabiting the Indian Ocean coastal strip of Kenya and Tanzania. They represent the largest subgroup of the nine Mijikenda peoples, a conglomeration of culturally and linguistically related ethnic groups that share common origins and historical myths. Unlike their Mijikenda counterparts, the Digo people are unique in their spread across the national borders between Kenya and Tanzania and in their near-universal embrace of Islam. This interplay of traditional Bantu identity, Islamic Swahili influences, and the contrasting political contexts of the two countries has shaped a complex and dynamic society. This article explores the Digo people through a neutral lens, examining their social organization, economic practices, religious beliefs, historical context, and contemporary situation.

The origins of the Digo people are closely intertwined with the history of the broader Mijikenda peoples. Oral tradition, supported by linguistics and archaeological evidence, states that the ancestors of the Mijikenda migrated from a mythical land to the north called Shongwaya, believed to have been located in present-day Somalia. This migration is believed to have occurred between the 16th and 17th centuries, prompted by conflict with pastoralist Oromo groups.

Upon arriving on Kenya’s coastline, the nine groups settled in strategically fortified hilltop sites known as “kaya.” These settlements, now sacred forests and UNESCO World Heritage Sites, served as the political and spiritual centers of each group. The Digo people initially settled at Kaya Kinondo, located in what is now Kwale County, Kenya, which is still considered their spiritual homeland.

From these initial settlements at Kaya, the Digo gradually expanded southward along the coast. This movement was driven by a combination of factors, including population growth, the search for agricultural land, and commercial opportunities. Their southward migration eventually led them to cross into what is now northern Tanzania, settling in areas around Tanga, Mwanga, and Pangani. This expansion made them the only Mijikenda group with a significant presence in both Kenya and Tanzania, creating a transnational community with strong kinship, economic, and cultural ties that spanned political boundaries.

Their relationship with the Swahili coast was also crucial in shaping their history. For centuries, the Digo people interacted with Arab, Persian, and Swahili traders who controlled trade in the Indian Ocean. This interaction led to significant cultural exchange, most notably the adoption of Islam by the Digo people, a process that intensified in the early 20th century. This religious conversion distinguished the Digo people from most other Mijikenda groups, who largely retained their traditional beliefs or later adopted Christianity.

The Digo society is organized around a complex matrilineal kinship system. This means that lineage, identity, and inheritance are traced through the mother’s line. An individual’s clan affiliation (fuko) is determined through their mother. This matrilineal system distinguishes them from many neighboring Bantu societies, which follow predominantly patrilineal systems.

Matrilineal clans are the basic units of social organization. These clans are widespread and not limited to a single geographic area, meaning that members of the same clan can be found in different villages throughout Kenya and Tanzania. Historically, clans played a central role in land ownership, marriage regulation, and conflict resolution. Although their importance has diminished somewhat with the introduction of modern legal systems and individual land ownership, clan identity remains an important aspect of Digo personal identity and social relations.

Despite the matrilineal system, the daily family structure is often patrilineal, with both spouses typically living in or near the father’s home. However, the mother’s eldest brother (mtumba) retains significant authority over his sister’s children, often playing a more significant role in their upbringing, discipline, and inheritance matters than their biological father. This interplay between paternal residence and matrilineal descent creates a unique dynamic within the family and community.

Society is also organized into age groups, although this practice has become less prominent. Traditionally, young men were indoctrinated in groups, passing through different stages of life together, forming strong bonds and playing specific roles within the community. The village council of elders (ngambi) was the main governing body, responsible for managing village affairs, enforcing customary law, and performing rituals. These elders were guardians of tradition and played a vital role in maintaining social cohesion. Today, these traditional structures coexist with modern forms of governance, including government administrators and elected officials.

Digo’s economy has traditionally been based on subsistence farming. The fertile coastal climate has allowed for the cultivation of a variety of crops. Staple foods include maize, cassava, rice, and beans. Tree crops are also vital, particularly coconuts, cashew nuts, mangoes, and oranges. Coconut trees, in particular, provide a versatile source of livelihood, providing food (coconut meat and milk), beverages (palm wine or “mnazi”), building materials (fronds), and income from the sale of dried coconut.

In addition to agriculture, fishing plays an important role in the economies of coastal communities. Men use traditional sailing boats (dhows) and small vessels to fish in the Indian Ocean, providing a source of protein and income. Historically, the Digo people also engaged in long-distance trade, acting as intermediaries between inland communities and Swahili coastal towns. They traded agricultural produce, ivory, and copal gum for manufactured goods such as cloth, tools, and beads.

In modern times, Digo’s economy has diversified, but it also faces significant challenges. The growth of tourism along the Kenyan and Tanzanian coast has created jobs in hotels, restaurants, and related services. However, these benefits have not been equally distributed, and tourism development has also led to land loss and resource conflict.

Access to land remains a pressing issue. Population pressures, land grabbing by individuals and companies outside the community, and the lack of formal land titles for many smallholder farmers have led to land insecurity and poverty. Many young people in Digo now work as casual laborers in urban areas such as Mombasa and Tanga, or participate in the informal economy, such as operating motorcycle taxis (“boda bodas”).