Among the mosaic of ethnic groups that make up Nigeria’s Middle Belt region, the Rukuba people (also known as the Bache) stand out as a distinct community with a unique social structure and history deeply rooted in the landscape of the Jos Plateau. Residing primarily in the Bassa Local Government Area of Plateau State, the Rukuba people have maintained a strong cultural identity, defined by their agricultural practices, clan organization, and traditional belief system, despite facing the pressures of modernization and regional conflicts. This article provides an impartial overview of the Rukuba people, exploring their social and political organization, economic livelihoods, cultural practices, and contemporary context.

The traditional lands of the Rukuba are located in the northwestern part of Plateau State, an area characterized by rocky terrain, rolling hills, and grassy savannah. This environment has directly influenced their livelihoods and settlement patterns, making agriculture the primary economic activity. The climate, characterized by a distinct rainy season and a dry season, determines the annual agricultural cycle around which most aspects of Rukuba life revolve.

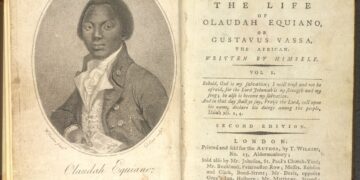

Like many ethnic groups in central Nigeria, the history of the Rukuba people’s origins is preserved in oral tradition rather than written records. These oral accounts point to a migration from the east. The most common story is that their ancestors first settled on a large, isolated, rocky hill range known as “Ogo Rukuba,” or “Mount Rukuba.” This location served as a natural defensive stronghold against neighboring groups and slave raids, allowing their culture to develop in relative isolation. Over time, as the population grew, they descended the hill and established the scattered settlements that make up the Rukuba lands today. This origin story continues to play an important role in their collective identity, with Mount Rukuba serving as a central spiritual and historical symbol.

The foundation of Rukuba society lies in its complex clan system. The people are divided into approximately twenty patrilineal clans (uniu), each with its own chief, traditions, and defined roles within the wider community. Membership in a clan is the basis of personal identity and determines an individual’s rights and obligations, including land ownership, choice of marriage partner (exogamy is the norm), and participation in rituals.

Traditionally, the political structure of the Rukuba people was decentralized, with each clan operating as a semi-autonomous unit. However, there was recognition of central authority in the person of the Rukuba chief, known as Utu Ugo. Utu Ugo was not an absolute ruler, but rather served as the primary custodian of tradition, the spiritual leader, and the final arbiter of inter-clan disputes. His authority derived from his religious standing and his ability to maintain harmony between the people, the land, and the spirits of the ancestors. He was assisted by a council of clan chiefs and elders who represented the interests of their communities.

Age groups (zage) were also an integral part of the social organization. Individuals, especially men, were grouped into age groups that underwent initiation together and formed strong, lifelong bonds. These groups were responsible for communal work tasks, such as clearing farmland, building houses, and defending the community. Age groups also played a role in maintaining social discipline and transmitting cultural values from one generation to the next. Although the influence of age groups has diminished, the concept still influences social relations.

The Rukuba economy is largely based on subsistence farming. They have mastered the cultivation of crops well adapted to the soil and climate of the plateau. The staple and most culturally important crop is the African rice “acha” (also known as fonio), a nutritious and drought-resistant grain. Other staple crops include millet, sorghum, potatoes, carrots, maize, and a variety of vegetables.

The division of labor in agriculture is clearly defined by gender. Men are responsible for the arduous tasks of clearing new land, plowing fields, and building mounds for planting potatoes. Women are responsible for planting seeds, weeding, harvesting most crops, and preparing food. Women often work collectively in each other’s fields, strengthening community bonds.

In addition to crop cultivation, the Rukuba people practice small-scale animal husbandry. They raise goats, sheep, and poultry, which serve as sources of protein and are used in ceremonial occasions, rituals, and sacrifices. Historically, hunting was also an important economic activity, providing meat and serving as a sign of masculinity. However, increasing population and deforestation have significantly reduced wild game populations, making hunting less important in the modern era. Other economic activities include pottery making (primarily done by women) and the manufacture of iron tools and weapons (carried out by blacksmiths).

In recent decades, the Rukuba people have faced numerous challenges that have impacted their traditional way of life. The introduction of modern governance, a national legal system, and a cash economy has eroded the authority of traditional political structures such as the Council of Elders and the Otu Ogu.

The most pressing challenge is communal conflict. The Bassa Local Government Area has been the site of frequent and sometimes violent tensions between the Rukuba people and their neighbors, particularly the Irigwe people. These conflicts often revolve around land and resource ownership, political representation, and historical disputes. These conflicts have resulted in loss of life, destruction of property, and displacement of populations, disrupting agricultural cycles and creating persistent insecurity. The dynamics of these conflicts are complex and exacerbated by broader ethnic and religious divisions in Nigeria.

Furthermore, environmental pressures, including deforestation, soil degradation, and climate change, are impacting agricultural productivity, threatening food security. The migration of young people to urban areas in search of education and employment is also contributing to the erosion of traditional cultural practices, with the younger generation struggling to maintain their language (Kuchi) and their knowledge of ancient rituals and customs.