In recent times, African Union officials questioned how Africa could deepen trade ties with the U.S. under what they called “abusive” tariff proposals. The top U.S. diplomat for Africa dismissed allegations of unfair U.S. trade practices. At the time, Ambassador Troy Fitrell said proposed U.S. import tariffs were not yet implemented, and negotiations were ongoing to create a more reciprocal trading environment, including through the renewal of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). The initiative grants qualifying African nations duty-free access to the U.S. market and is due to expire in September. Washington’s tariff plans have also added to cooling diplomatic ties with African countries, as some economies—including Lesotho and Madagascar—warned that even a baseline 10% levy could threaten critical exports such as apparel and minerals.

Under the circumstances, recently the White House notably brokered a peace deal between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, putting a preliminary end to hostilities and Rwandan-backed rebel groups fighting DRC troops in the east of the country for several months. Furthermore, the United States President Donald Trump invited the heads of state from Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mauritania, and Senegal to attend the summit from July 9 to 11. US State Department officials said that the summit will focus on critical minerals, economic cooperation, trade opportunities, and regional security.

In his first term, Trump’s isolationist strategy and “America first” foreign policy led him to advocate for Congress to reduce development programs. Most of them are in Africa. While administration officials such as Mike Pompeo and Trump family members—including his wife, Melania, and his daughter Ivanka—visited several countries in Africa, Trump never actually visited himself. During his four years in the White House, Trump welcomed only two Sub-Saharan African heads of state: Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria and Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya. His administration did not host a US-Africa summit; meanwhile, Russian President Vladimir Putin spectacularly kicked off a series of Russia-Africa summits, the first taking place in Sochi in 2019.

Trump announced the aid freeze on his first day in office in January in line with his “America First” foreign policy, while Trump’s recent tariffs have raised fears of the end of a trade deal between the US and Africa meant to boost economic growth. But US Senior Advisor for Africa Massad Boulos told BBC’s Newsday that Africa was “very important” to Trump and downplayed reports that the US was planning to close some of its missions on the continent. “He highly values Africa and African people,” Mr. Boulos added. Also, a White House official claimed on July 3 that “President Trump believes that African countries offer incredible commercial opportunities that benefit both the American people and our African partners.” Nevertheless, the summit has sparked curiosity and raised concerns about a deeper agenda. With no clear framework, critics question whether the summit’s true purpose is rooted in securing access to resources and military influence or countering China’s expanding presence in Africa. What does this mean for these nations and the U.S.?

Why Africa Is Central to US Trade Strategy

Africa is a significant producer of valuable metals and minerals. African countries export a range of precious minerals, such as uranium for the generation of nuclear energy, platinum for use in jewelry and industry, nickel for stainless steel, magnets, coinage, and rechargeable batteries, bauxite as a major supplier of aluminum ore, and cobalt for color pigments. Additionally, Africa possesses significant reserves of oil, gas, coal, and renewable energy sources (such as solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal power). However, China dominates the processing and production of nearly all critical minerals, which represents a national security vulnerability to the United States. Of note, there are promising new technologies emerging in the United States that represent an alternative to shipping minerals to China for refinement.

Christopher Afoke Isike, a professor of African politics and international relations at the University of Pretoria, South Africa, describes Trump’s handpicked guests for his US summit as “low-hanging fruit” in his quest to counter Chinese and Russian influence in Africa. “On one hand, Trump is desperate for some deal to show to his base that he is getting results for America. But some of these also align with his focus on countering Chinese influence in Africa and malign Russian activity, which undermines US interests on the continent,” he told CNN. “Most of the regional powers in Africa are either in BRICS as key members or are aspiring to join as key partners,” Isike said, adding that “these five countries (attending the US summit) do not fall into that category and as such are a kind of low-hanging fruit.”

The five nations whose leaders meet Trump in July represent a small fraction of US-Africa trade, but they possess untapped natural resources. For example, Gabon holds some of the world’s richest manganese deposits and is the second-biggest exporter globally, according to U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) data in 2024. A key component in batteries, manganese is the fourth most widely used metal in the world after iron, aluminum, and copper. While Guinea-Bissau has large deposits of bauxite and phosphates, Liberia is rich in minerals, including gold, diamonds, and iron ore. Also, Mauritania began producing crude oil in 2006 and saw one of the largest discoveries of natural gas in recent years in 2019. The volume of gas potentially trapped in the area is equal to around 8.9 billion barrels of oil equivalent. In addition, with significant reserves of base metals and limestone, Senegal also has a mining sector focused on gold, phosphate, and zircon.

How Trump’s Selective Africa Policy Affects These Five Nations

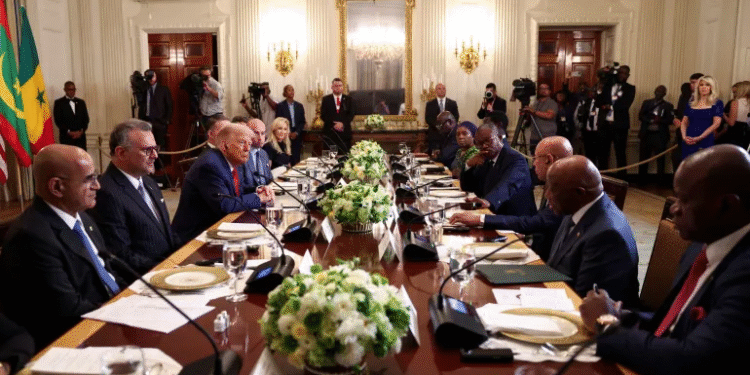

During the meeting, Trump described trade as a diplomatic tool. Trade “seems to be a foundation” for him to settle disputes between countries, he said. “You guys are going to fight; we’re not going to trade,” Trump said. “And we seem to be quite successful in doing that.” He added, addressing the African leaders, “There is a lot of anger on your continent.” As he spoke, the US administration continued sending out notifications to developing countries about higher tariff rates effective from August 1.

The five Western African nations were not among them. The portion of the lunch meeting that was open to the press didn’t touch much on the loss of aid, which critics say will result in millions of deaths. “We have closed the USAID group to eliminate waste, fraud, and abuse,” Trump said at the summit. “And we’re working tirelessly to forge new economic opportunities involving both the United States and many African nations.” In their speeches, each African leader adopted a flattering tone to commend Trump for what they described as his peace efforts across the world and tried to outshine one another by listing the untapped natural resources their nations possess, an observer says.

The U.S. faces growing competition in Gabon not only economically but also strategically. Beijing has drawn closer to Gabon with naval diplomacy, providing medical aid by naval hospital ship to nearly 7,000 civilians, and is rumored to be exploring the establishment of a military base in the country. The rumored base would be the second on the continent and the first on Africa’s west coast. While the United States has offered security training and supported Gabon’s regional peacekeeping through ECCAS and the AU Standby Force, the future strategic relationship between the two countries will depend on how and to what extent the United States escalates its engagement to measure up with China.

To be fair, Nicaise Mouloumbi, head of a leading non-governmental organization in oil-rich Gabon, said the Trump administration’s focus on Africa was down to increasing competition from rival powers—including China and Russia—for its prized resources. “All these [invited] countries have important minerals: gold, oil, manganese, gas, wood, and zircon—Senegal, Mauritania, and Gabon, in particular,” he told the BBC. Mr. Mouloumbi added that the US might be most keen to strengthen ties with Gabon not only because it had “strategic” minerals like manganese and uranium, as well as oil, but also because it was strategically located along the Gulf of Guinea, with a coastline of about 800 km (500 miles). It could host a US military base that America plans to build in the region, Mr. Mouloumbi said. Mr. Diagne made a similar point about piracy, saying that “maritime terrorism in the Gulf of Guinea has become an extremely important issue” for the US.

President of Gabon Brice Clotaire Oligui Nguema told Trump that “We are not poor countries. We are rich countries when it comes to raw materials. But we need partners to support us and help us develop those resources with win-win partnerships.” “We also want our raw materials to be processed locally in our country so that we can create value and create jobs for youth.” “In order to do this local processing, we need eight to 10 gigawatts of electricity. Again, this is an open bid; any American company that wants to invest in electricity in Gabon is welcome to take advantage of that opportunity.” According to Tafi Mhaka, a social and political commentator from South Africa who analyzed the event from an African perspective, Gabon’s President Brice Clotaire Nguema talked of “win-win partnerships” with the US but received only a lukewarm response.

In contrast, the United States’ engagement with Guinea-Bissau has been limited. It is one of the only four African countries in which the United States does not have a physical presence after abandoning its embassy in 1998 when the civil war started. Total U.S.-Guinea-Bissau trade volumes in 2024 were at $3.5 million (almost entirely U.S. exports to Guinea-Bissau ($3.4 million vs. $0.1 million imports)), compared to China, which exported $62.6 million in 2023. This summit may be Washington’s opportunity to re-engage before the geopolitical window closes in light of China and Russia’s involvement.

Liberia is one of America’s closest historical allies in Africa. Past U.S. presidents and secretaries of state have made official visits, and Washington played a leading role in Liberia’s post-conflict recovery and response to the Ebola crisis. However, the closure of USAID will deeply affect Liberia, where aid comprises 1.6% of gross national income, making it the largest cut relative to GDP of any country globally. In 2024, total trade between Liberia and the United States was $292.9 million (U.S. exports to Liberia totaling $220.4 million and imports totaling $72.5 million). In comparison, total trade between Liberia and China was $13.06 billion in 2024. 42% of Liberia’s total imports came from China in 2023.

The Liberian President Joseph Nyuma Boakai, in a statement, “expressed optimism about the outcomes of the summit, reaffirming Liberia’s commitment to regional stability, democratic governance, and inclusive economic growth.” During the meeting, Trump reacted with visible surprise to Boakai’s English-speaking skills, which he praised. Mhaka said Trump seemed unaware English is Liberia’s official language and has been since its founding in 1822 as a haven for freed American slaves, which was perhaps less shocking than the colonial tone of his question. His astonishment that an African president could speak English well betrayed a deeply racist, imperial mindset.

Mauritania’s positioning as a relatively stable country within the Sahel has increased the interest amongst countries like China, Russia, the United States, and the European Union, who are eager to engage with a country in its strategic location and its potential for energy supply. In 2024, the United States’ total goods trade with Mauritania was $142.6 million ($139.8 million in U.S. exports and $2.9 million in U.S. imports), but it was not amongst the top exporters or importers in the country. China was the second largest recipient of Mauritanian exports following Canada, with the country mainly exporting minerals like gold, iron, copper, and fishery products. Mauritania’s vast area of land makes it suitable for green energy production such as solar and wind energy installations. Meanwhile, its counterterrorism efforts have been viewed as successful, which is of interest to countries trying to help bring regional stability and curb immigration.

“We have a great deal of resources,” said Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, president of Mauritania, listing rare earths, as well as manganese, uranium, and possibly lithium. “We have a lot of opportunities to offer in terms of investment.” Mhaka is of the opinion that in one especially embarrassing moment, Ghazouani described Trump as the world’s top peacemaker—crediting him, among other things, with stopping “the war between Iran and Israel.” This praise came with no mention of the US’s continued military and diplomatic support for Israel’s war on Gaza, which the African Union has firmly condemned. The silence amounted to complicity, a calculated erasure of Palestinian suffering for the sake of American favor.

Senegal’s former ambassador to Washington, Babacar Diagne, said the invitations to the African leaders reflected the recent “paradigm shift” in US policy towards the continent. “It’s not like before with the Democrats. There were two strong points with them: poverty reduction and development issues, through AGOA and other initiatives. All that is over,” Mr. Diagne told the BBC. For Mhaka, Senegal’s President Bassirou Diomaye Faye even asked Trump to build a golf course in his country. Trump declined, opting instead to compliment Faye’s youthful appearance.

Aftermath of Trump’s Summit: Key Takeaways and What’s Next

To be blunt, Gabon, Liberia, Mauritania, and Senegal are among 36 countries that might be included in the possible expansion of Trump’s travel ban. While experts said that the meeting highlighted the new transactional nature of the relationship between the U.S. and Africa. While challenges abound, there may very likely be opportunities for increased engagement if both sides play their cards right.

In a moment when African leaders had the chance to push back against a resurgent colonial mindset, they instead bowed—giving Trump space to revive a 16th-century fantasy of Western mastery. Landry Signé, a senior fellow at the Global Economy and Development, Africa Growth Initiative, suggested that African countries and the African Union should have their own U.S. strategy that outlines a clear value proposition that is ready to be deployed when opportunities for engagement—like this summit—come to fruition.

Overall, the shift is “a high-stakes gamble that aligns with America’s goal to reset its influence in Africa through investment but also to counter China and foster economically self-reliant African partners,” Isike added. “Enabling Africa to be self-reliant is not because he (Trump) loves Africa, but because he doesn’t have patience with countries that only want handouts from the US,” Isike said, adding that “these trade deals and the meeting (this week) align with the US’ priority to favor countries that are able to help themselves.”