Kirdi, a collective name for many cultures and ethnic groups who inhabit Cameroon, Nigeria, and Chad. The group makes up 18% of the total population. Among the members of Kirdi are Bata, Fata, Mada, Mara, and Toupori. The Kirdi speak Chadic and Adamawa languages.

Historians noted that the term was applied to various ethnic groups who refused to convert to Islam after Islamic conquests of the region and was a pejorative, although some writers have reappropriated it. The term comes from the Kanuri word for pagan; the Kanuri people are predominantly Muslim. According to some scholars, in the eleventh century, people such as the Fulani converted to Islam and spread throughout West Africa in the following centuries. They had also begun migrating to Cameroon, where they had attempted to convert the pre-existing peoples. Therefore, the kirdi, have fewer similarities culturally or linguistically as they do in their general geographic dispersal, primarily situated in the arid steppe and savannahs of North and Far North regions of Cameroon.

The Kirdi tribe are still living the same traditional way now, as they have done for at least 200 hundred years. Most of the Kirdi are farmers who raise crops on hillside terraces. Peanuts, maize and millet are among the main crops. Melons, pumpkins, and beans are also cultivated. Millet and other cereals are usually grown on the mountains or hill slopes, while other crops are raised in gardens near the houses. Cotton, indigo (used for dyeing) and plants that are used for hunting, religious medicines and other purposes are also grown. Similarly, Kirdi man’s work includes crafting leather, making baskets, spinning, weaving, and building. The Kirdi and produce distinctive types of pottery. Women make clay objects, train the small children, prepare the meals and do other household activities. A woman may also raise her own crops on a small plot of land. The profits earned from selling these crops belong to the woman. Children take care of the small animals and help their older siblings or parents do other household chores.

The kirdi have some traditional foods specific to their specific region, which reflect some of the many staples common to West Africa. The most popular staple is fufu, which generally refers to a dough made from boiled and pounded starchy provisions such as mandioca, plantains, yams, cassava, or malanga. In some recipes, fat is added to fufu for added fortification. This fat can derive from animals or plants. Local ingredients include the following staple foods in Cameroon: cassava, yams, rice, plantain, potato, sweet potatoes, maize, beans, millet, a wide variety of cocoyams, and many vegetables.

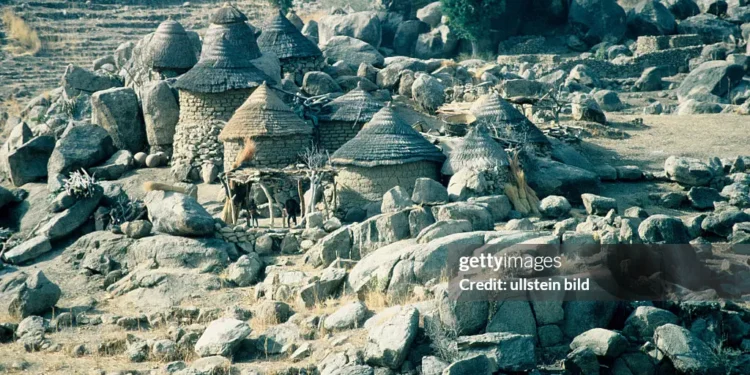

Traditionally, houses in kirdi were grouped into small village settlements by clan or lineage. The villages were clustered around mountain peaks that could not easily be accessed by outsiders. They were protected by mud-brick barriers that had been overgrown by thorn bushes. Today, their villages are composed of several round buildings made of mud-brick and thatched roofs. The buildings are connected to one another by woven straw fences or hedges. The buildings are positioned so that there is an open area in the center. Each home has a kitchen, an attic and a room for the husband while the wife lives in a separate hut. Separate rooms are added to the house when the children reach puberty. Young males are given their own square huts, where they live until they are married.

However, the Minorities at Risk Project’s Assessment for Kirdi in Cameroon published in December, 2003 stated that the Kirdi are isolated and relatively impoverished, but do not have much interaction with the central government. Whether due to their isolation or the ruling governments neglect, the Kirdi are rarely included in the Cameroonian political sphere. The main political disputes in Cameroon exist between the Francophone community and the English-speakers of western Cameroon. While prior data indicates that the Kirdi would prefer a measure of autonomy, in essence their geographic position and lifestyle provides them this already, and the Kirdi political movement remains an extremely small component of President Biya’s ruling coalition. Presumably, if the Kirdi continue to live in seclusion and maintain their comparatively minimal influence in central government, the Kirdi are likely to preserve their current lifestyle.

At one time, all of these groups were completely pagan. Christian missions have had some success among the Kirdi in recent years. While kirdi generally bears the meaning “pagan,” in opposition to the Fulani and other Muslim groups, they do not all practice atavistic customs and pagan rituals, many have converted to Christianity and are increasingly self-identifying as a Christian political bloc, to contrast the Muslims opposing blocs. Today, some have become Muslim and wear traditional Islamic dress. Although two of the Kirdi groups (the Fali and the Mousgouma) have partially converted to Islam, most of the groups still follow their traditional ethnic religions. Most Kirdi believe in a single god who is the creator of all things and who keeps his creation in order.