The year 2025 opens with yet another chapter in Afro-Sino relations, as China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi landed in Africa from January 5–11—his 57th visit since 2013. But this isn’t just diplomacy; it’s deal-making. One of the latest? A $31.6 million pact with ECOWAS to build the bloc’s new headquarters is set to open in February 2025. Another ribbon-cutting, another sign of China’s deepening footprint on the continent. Another prominent landmark project funded by the Chinese is the $200 million African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa, which was a gift from China.

Today, the partnership has evolved into a comprehensive relationship that goes well beyond physical construction because the Chinese interests in Africa have increasingly spanned several sectors like digital technology, clean energy and green development, security and defense, and soft power through cultural and educational initiatives. This article explores the emerging trends, key data points, and strategic challenges in this broadened framework.

A New Era of Digital Transformation

China’s digital engagement in Africa is accelerating rapidly as Chinese technology giants such as Huawei and ZTE are installing thousands of kilometers of fiber-optic networks and also spearheading the rollout of 5G networks, smart city projects, and cloud computing infrastructure on the continent.

For instance, many Chinese companies have secured huge contracts to develop next-generation digital networks in key markets like Kenya and South Africa, with estimates suggesting that about 400 million Africans have already benefited from broadband connectivity and mobile internet access across the continent, but this digital expansion is not limited to network construction, as Chinese investments are also targeting burgeoning fintech and e-commerce sectors. According to a recent market analysis, Africa’s fintech market is projected to reach a value of around US$150 billion by 2025, fueled in part by Chinese-backed digital payment solutions and mobile money platforms that have transformed everyday financial transactions in countries such as Nigeria and Uganda.

African entrepreneurs now have access to resources that were previously the preserve of Western tech giants through the growing presence of Chinese startups and venture capital. This paradigm towards China has created the required kickstart supports for local job creation and capacity building, which is a critical element for long-term sustainable development.

Clean Energy and Green Development

China’s involvement in African fossil fuel projects has drawn criticism in the past, but there is a notable pivot toward green energy cooperation. China now leverages its technological expertise in renewable energy to meet both its own domestic sustainability goals and Africa’s urgent need for clean energy.

Recent efforts have included funding hydropower projects, wind farms, and massive solar power plants throughout Africa. One well-known ambitious project, the Noor Ouarzazate solar power plant in Morocco, is one of the biggest concentrated solar power plants in the world whose funding, engineering, and construction assistance were supported by China.

Another prominent project is the construction of the Garissa Solar Power Plant in Kenya, which spans 85 hectares, costs over $100 million, and was funded by Jiangxi International, a Chinese company. These investments are unquestionably anticipated to generate significant employment opportunities and improve local industrial capacities and can, in turn, reduce the debt risks frequently connected with large-scale infrastructure loans.

Security and Defense

The security and defense strategy of China in Africa has evolved dramatically since the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation’s (FOCAC) launch in 2000, when its military engagement was virtually nonexistent compared to today, when China’s People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) largest overseas deployment area is Africa.

In July–August 2024, the “Peace Unity-2024” exercise held with Tanzania and Mozambique sees approximately 1,000 PLA troops participating in a comprehensive two-week drill that combines land and sea operations, which include maritime patrols, search and rescue missions, and live-fire drills—using diverse weapon systems such as small arms, heavy artillery, and micro unmanned aerial vehicles.

West Africa will also likely feature in the PLA’s training schedule in 2025 as China is willing to extend its patrols into the Gulf of Guinea, a region rich in minerals and hosting extensive Chinese fishing operations. China will also launch a program in 2025 to train 6,000 African senior officers, 500 junior officers, and 1,000 law enforcement officers by 2027.

This is an indication of massive progress backed by factual data that showed that since 2000, China has significantly expanded its military footprint by conducting 19 exercises and 44 naval port calls in Africa.

Expanding China’s Cultural and Educational Footprint

In the last ten years, China, in its quest to achieve its aim of cultural and educational presence in Africa, has started a number of cultural and educational programs with the goal of building lasting relationships with African people. One is the creation of the Confucius Institutes, which now number over 61 institutions throughout Africa.

These institutions are intended to foster the Chinese language and culture, act as venues for educational exchanges, and create cooperative links between the academic communities of China and Africa.

China didn’t stop at just opening institutes across the continent but also provided scholarship programs for educational engagement in Africa, as it has attained the status of being the largest provider of scholarships to sub-Saharan Africa, offering approximately 12,000 scholarships annually.

The scholarships are awarded to deserving students pursuing studies in STEM fields, agriculture, and medicine to reinforce a pipeline of human capital that is exposed to Chinese educational models and technological practices, further earning the Chinese their educational rigid blocks in Africa.

In addition, China has also pledged in 2024 to train around 40,000 African teachers over the next three years to enhance research output and cultivate talent in emerging fields such as artificial intelligence and the digital economy.

Challenges and Opportunities in the Evolving Partnership

- Debt Sustainability and Financial Transparency:

China remains Africa’s largest bilateral lender, with cumulative loans exceeding $170 billion between 2000 and 2022. While these funds have funded vital infrastructure, such as the upgrades to Uganda’s Entebbe Airport and Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway, the opaqueness of loan terms and collateral clauses (such as escrow accounts for revenue sequestration) has heightened concerns about sovereignty risks; a 2024 data source found that approximately 40% of low-income African countries are in or near debt distress, with loans from China significantly contributing to this vulnerability.

Despite these obstacles, recent efforts indicate a shift toward accountability, as China’s 2024 FOCAC pledge of $50.7 billion prioritizes “targeted” projects over large-scale infrastructure, reflecting a cautious approach amid global economic pressures.

Debt relief options are still scarce, but requests for legally required transparency frameworks to reduce hidden debt risks are being considered, as are refinancing and deferrals for crucial partners.

- Industrialization and Trade Imbalances

Total commerce dealings between China and Africa reached $280 billion yearly in 2024, yet structural disparities still exist because Africa has persistent trade deficits as a result of its primary exports of raw materials (such as minerals and oil) and imports of manufactured goods from China.

In order to preserve value-added benefits, African countries such as Zambia are negotiating indigenous processing mandates (such as copper refining).

China-Africa trade soared to $280 billion in 2024, a staggering figure—but the imbalance is hard to ignore because Africa is stuck in a cycle of trade deficits, shipping out raw materials while importing a flood of manufactured goods from China. The structure hasn’t changed. The power dynamic hasn’t shifted. And until Africa moves beyond being a supplier of raw resources, that gap isn’t closing anytime soon.

In order to preserve value-added benefits, African countries such as Zambia are negotiating indigenous processing mandates (such as copper refining). Also, massive industrial projects like the BAIC car plant in South Africa and the lithium battery factories in Morocco are intended to support domestic production and can potentially place Africa in the international supply chains. This is an unquestionable proof that “new quality productive forces” like green tech and advanced manufacturing might spur Africa’s economic modernization when combined with fair technology transfer.

- Geopolitical Rebalancing and the Road Ahead

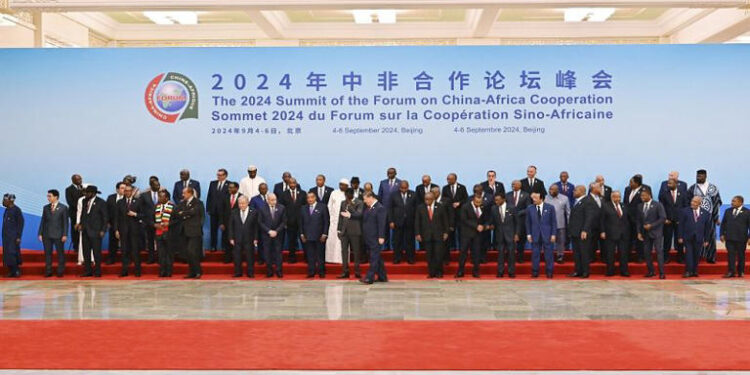

The expanding influence of China in Africa continues to recalibrate global power dynamics, challenging longstanding Western hegemony and contributing to the emergence of a multipolar world. Annual high-level diplomatic engagements—noted by Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s recurring Africa tours—reflect Beijing’s commitment to a “win-win” South–South cooperation model. African governments are also increasingly using their collective bargaining power to negotiate more favorable terms. At FOCAC 2024, Kenya secured critical funding for its railway project, while Ethiopia and Mauritius successfully finalized currency swap agreements to stabilize bilateral trade. These moves are a clear indication of Africa’s strategic pragmatism—leveraging Chinese investment to drive infrastructure development while seeking mechanisms to safeguard political and economic independence.

Looking forward, the Afro-Sino partnership’s trajectory is closely tied to alignment with Africa’s Agenda 2063 and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Concurrently, private sector engagement is on the rise, as illustrated by DP World’s $2 billion investment in African ports, even as disputes over labor practices and profit-sharing underscore existing governance challenges. Enhanced transparency, strengthened local industries, and the adoption of debt-for-climate swap mechanisms are critical for transforming the Afro-Sino partnership into a model of equitable and sustainable globalization.

Conclusion

The Africa-China partnership is expected to be vibrant in 2025, with a wide range of activities that extend well beyond the building of tangible infrastructure like the green energy sector, which is promoting sustainable development and job creation, while digital transformation initiatives are allowing millions of Africans to connect and participate in a contemporary digital economy and giving them a commanding stature on the tech stage.

However, challenges across various sectors cannot be underestimated, and the African leadership should address persistent issues with careful management. It is quite imperative that undiverted focus across institutional innovations such as public-private partnerships, local currency settlements, and increased transparency in lending practices is also critical to ensuring that this broadening partnership delivers on its promise of mutual benefits.

As Africa asserts greater control over her economic destinies and as China recalibrates its global strategy in response to both internal pressures and external competition, the relationship, however, is poised to transform from one of simple transactional exchanges into a genuine partnership of equals.