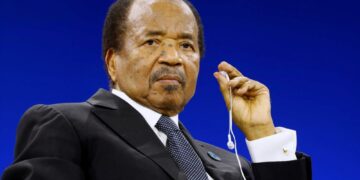

Ahmadou Baba Ahidjo was born on August 24, 1924, in the town of Garoua, in northern Cameroon. He came from a modest family, with his father being a village chief. Ahidjo belongs to the Fulani, a Muslim ethnic group prevalent in West Africa. He received his primary education in a Quranic school, then attended a regional French school, before completing his secondary education in Yaoundé, the country’s capital. From an early age, Ahidjo displayed a keen intellect and a strong ability to communicate, which qualified him for a position with the French postal administration in 1942.

Working as a postal clerk was a turning point in his life. It gave him the opportunity to travel and explore the various regions of Cameroon, discovering the depth of the country’s ethnic and cultural diversity. This work also gave him a solid understanding of how the French colonial administration operated, which he would later leverage in his political career.

In 1947, Ahidjo began his political career by being elected to the Regional Assembly of Northern Cameroon. In 1953, he was elected as a Cameroonian representative to the French National Assembly, giving him a broader political platform. During this period, he began to network with French and Cameroonian politicians and gained experience in legislative work.

Cameroon at that time was going through a difficult transition. It was divided into two parts: French Cameroon and British Cameroon, both under UN mandate. Independence movements were growing, the most notable of which was the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon (UPC), led by Reuben Oum Nyobé, who embraced a revolutionary and radical approach aimed at complete independence and unity.

Ahidjo did not belong to this movement, but preferred a more moderate and cooperative approach with the French. He believed that independence should come gradually and through understanding with the colonial power, not through armed conflict.

In 1957, the French appointed Ahmadou Ahidjo as Prime Minister of Cameroon, a move seen as a reward for his moderate approach. In this position, Ahidjo was responsible for managing the country’s affairs and negotiating the terms of independence with the French. The period between 1957 and 1960 was a crucial one in Cameroon’s history. Ahidjo faced significant internal challenges, most notably the armed rebellion led by the Union of Cameroonian Peoples (UPC), which viewed Ahidjo as a French tool.

Ahidjo pursued a repressive policy toward the rebels, cooperating with French forces in their pursuit. This policy resulted in the deaths of thousands of people, including the movement’s leaders. Some historians believe that the suppression of this rebellion was necessary to achieve stability, while others view it as a brutal act aimed at weakening the radical opposition.

On January 1, 1960, French Cameroon gained its independence. On this historic day, Ahidjo delivered a speech in which he emphasized the importance of national unity and the need to build a strong and stable state. After independence, Ahidjo was elected as the first president of the republic.

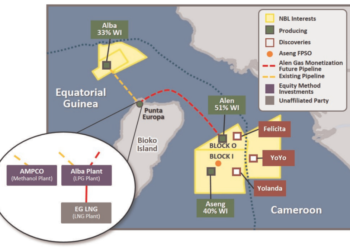

The next task was to unify French Cameroon with British Cameroon. The British part was divided into two regions: British Northern Cameroon and British Southern Cameroons. In 1961, a popular referendum was held, in which British Northern Cameroon chose to join Nigeria, while British Southern Cameroons chose to join Cameroon. On October 1, 1961, the Federal Republic of Cameroon was proclaimed.

Unifying the country was a historic event, but it also created significant challenges. The two regions differed in language (French and English), legal, administrative, and cultural systems. Ahidjo had to find a way to manage this enormous diversity.

In 1966, Ahidjo took a decisive step to consolidate his power. He merged all the country’s political parties into a single party, the Cameroon National Union (CNU). This was the only legal party in the country, effectively transforming Cameroon into a one-party system.

Ahidjo justified this move as necessary to achieve national unity and prevent the ethnic and political divisions that plagued many newly independent African states. He also believed that multipartyism caused chaos and hindered economic development.

In 1972, Ahidjo went further. He abolished the federal system and declared the United Republic of Cameroon. This decision aimed to increase political centralization and grant the central government in Yaoundé greater powers over the regions. Some considered this decision necessary to streamline administration and improve efficiency, while others saw it as a move to weaken the power of the English-speaking regions, which is considered the root of the secessionist conflict in the south of the country to this day.

Ahidjo’s reign was characterized by calm and security stability. He relied on a powerful security apparatus and brutally suppressed any opposition or protests. The press was restricted, and political freedoms were limited. Ahidjo focused on achieving economic development and was seen as a wise and pragmatic leader.

In the economic field, Ahidjo adopted a policy of central planning, with an emphasis on the agricultural sector. Under his rule, Cameroon was known as Africa’s “Green Island” due to its abundant production of agricultural crops such as cocoa, coffee, and cotton. Cameroon benefited from the high commodity prices of the 1970s, which allowed the government to invest in infrastructure projects such as roads, schools, and hospitals.

However, this policy was not without flaws. It relied heavily on foreign aid and international financing and failed to adequately diversify the economy. Administrative and financial corruption within the state apparatus was also criticized.

In foreign policy, Ahidjo followed a pragmatic approach. He maintained good relations with France, which remained the country’s main trading partner and largest donor. He also established diplomatic relations with both Western and Eastern countries and pursued a policy of non-alignment. Ahidjo played an important role in regional organizations such as the Organization of African Unity and was considered a moderate and influential African leader.