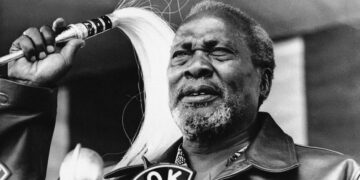

Julius Kambarage Nyerere, the first president of the United Republic of Tanzania, is considered one of the most prominent figures in modern African history. On the one hand, he is viewed as the father of the nation, a symbol of national unity, and a proponent of “African socialism” (ujama). On the other hand, his economic policies, which led to economic stagnation, and his centralized rule are criticized. Nyerere’s legacy cannot be understood without delving into the details of his life, from his humble upbringing, through his education abroad, to his nearly 24-year presidency.

Julius Nyerere was born in March 1922 in the village of Butiama, located on the shores of Lake Victoria in Tanganyika (now Tanzania). He belonged to the Zanaki ethnic group. He came from a modest family, as his father was a local chief. He received his primary education in local schools and then moved to St. Mary’s School in Tabarua, where he excelled academically. In 1943, he enrolled at Makerere University College in Kampala, Uganda, where he majored in history and economics. After graduating, Nyerere worked as a teacher.

This time as a teacher was crucial in shaping his political consciousness. He became aware of the differences between the education received by Africans and that of Europeans, and his sense of colonial injustice deepened. In 1949, Nyerere received a scholarship to the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, making him the first Tanganyikan to study at a British university. While studying at Edinburgh, he wrote a dissertation on racial discrimination in the British colonies. During this period, his concept of African nationalism and the need for liberation from colonialism began to crystallize.

After returning to Tanganyika in 1952, Nyerere returned to his teaching career, but his political activism continued. In 1954, he co-founded the Tanganyika African Union (TANU), a political party that aimed to achieve independence. Nyerere possessed unique oratory skills and an ability to connect with the masses. He advocated peaceful independence, rejected violence, and emphasized the importance of national unity. These positions set him apart from other liberation movement leaders in Africa, who adopted a more radical approach.

In 1958, Nyerere was elected to the Legislative Assembly. In 1960, he was appointed Prime Minister. He led negotiations with the British, and on December 9, 1961, Tanganyika gained independence. In 1962, Tanganyika became a republic, and Nyerere was elected its first president.

One of Nyerere’s most significant achievements was the unification of Tanganyika with Zanzibar in 1964, forming the United Republic of Tanzania. This unification was intended to prevent divisions and promote regional stability.

Nyerere’s presidency was characterized by a focus on social and economic development. In 1967, Nyerere launched the Arusha Declaration, a political document that became the foundation for “African socialism,” or Ujamaa. This ideology was based on several principles, such as reliance on collective ownership of the means of production, reducing dependence on foreign aid, considering agriculture as the foundation of economic development, and promoting national unity and rejecting tribalism.

Nyerere implemented these principles through bold policies. He nationalized the banking sector, industry, and foreign trade. He also launched the Village Socialization Program, which aimed to relocate rural populations from their scattered villages to communal villages to facilitate the provision of basic services such as education and health.

In the social sphere, Nyerere achieved significant achievements. Literacy rates rose dramatically, health services were made available in rural areas, and primary education was provided for all. These achievements were impressive, but they came at a high cost.

The Village Socialist Policy was controversial. This led to a decline in agricultural production, as farmers were unenthusiastic about collective action. The nationalization of industry and trade also weakened the economy and reduced foreign investment. At a time when many African countries were suffering from ethnic and tribal divisions, Nyerere succeeded in building a unified and homogeneous state with Swahili as the national language.

Nyerere was one of the most prominent advocates of African nationalism and liberation on the continent. He played a key role in establishing the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and was a staunch critic of the apartheid regimes in South Africa and Rhodesia. He supported liberation movements on the continent and hosted many of their leaders in Tanzania.

In 1978, the Ugandan army invaded Tanzania. Nyerere responded by sending Tanzanian troops into Uganda, overthrowing the regime of dictator Idi Amin. This decision was controversial, as Tanzania was a poor country, and military intervention was extremely costly. However, Nyerere justified the decision as necessary to defend his country’s sovereignty.

In 1985, Nyerere voluntarily stepped down from power, a rare decision in Africa. This decision was a clear message of his commitment to democracy and the free rotation of power. After stepping down, Nyerere remained a respected figure and political authority.

Nyerere’s legacy is complex. On the one hand, he is seen as the Father of the Nation, who united his country, achieved significant achievements in education and health, and was a symbol of African dignity. On the other hand, his socialist economic policies are criticized for leading to economic decline and the rise of corruption.

Quotes from Julius Nyerere:

“In Tanganyika we believe that only evil, Godless men would make the color of a man’s skin the criteria for granting him civil rights.”

Julius Kambarage Nyerere addressing British Governor-General Richard Gordon Turnbull, at a meeting of the Legco, prior to taking up the premiership in 1960.

“The African is not ‘Communistic’ in his thinking; he is — if I may coin an expression – ‘communitary’.”

Julius Kambarage Nyerere as quoted in the New York Times Magazine on 27 March 1960.

“Having come into contact with a civilization which has over-emphasized the freedom of the individual, we are in fact faced with one of the big problems of Africa in the modern world. Our problem is just this: how to get the benefits of European society – benefits that have been brought about by an organization based upon the individual — and yet retain African’s own structure of society in which the individual is a member of a kind of fellowship.”

Julius Kambarage Nyerere as quoted in the New York Times Magazine on 27 March 1960.

“We, in Africa, have no more need of being ‘converted’ to socialism than we have of being ‘taught’ democracy. Both are rooted in our past — in the traditional society which produced us.”

Julius Kambarage Nyerere, from his book Uhuru na Umoja (Freedom and Unity): Essays on Socialism, 1967.