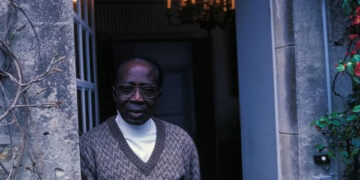

Ben Okri is a poet, novelist, short story writer, essayist, aphorist, playwright, and writer of film scripts. He grew up in a turbulent period in Nigeria’s history, witnessing civil war, which profoundly influenced his early works, which explored political violence and social chaos. These early experiences, coupled with the rich oral histories he grew up with, particularly from his mother’s tales, fuelled his imagination and gave him a unique perspective on reality, where the visible and invisible, the physical and the spiritual, intertwine.

He is also a cultural activist. He was knighted in 2023 for services to literature. Okri attended Urhobo College in Warri, Nigeria, and the University of Essex in Colchester, England. He has also received many honorary doctorates for his contribution to literature.

Okri returned to the UK in the late 1970s to study comparative literature at the University of Essex, which enriched his understanding of Western literary and philosophical theories and gave him additional tools to express his own vision. Okri worked as poetry editor for West Africa magazine between 1983 and 1986, and he also broadcast regularly for the BBC World Service between 1983 and 1985, honing his writing and editing skills.

Ben Okri’s writing challenges perceptions of reality. His literary style is widely categorised as “magical realism”, a classification Okri himself often rejects, preferring to describe his works as following “dream logic” or “spiritual realism”. He believes that reality transcends the physical and tangible and that there are multiple dimensions to reality, including myths, spirits, and ancestors. This profound understanding of reality, rooted in African traditions, is what distinguishes his writing.

In his work, Okri demonstrates a remarkable ability to blend the everyday with the miraculous, the familiar with the mystical. The characters in his fictional worlds intertwine with spiritual beings and supernatural events, creating a narrative texture rich with surprising details and complex symbolism. His language is poetic and lyrical, employing ingenious imagery and complex metaphors to create an immersive atmosphere that draws the reader into his unique worlds. His style is also notable for his ability to construct long, intertwined sentences that flow seamlessly to reflect the complexity of the thoughts and feelings he addresses.

His first novels, Flowers and Shadows (1980) and The Landscapes Within (1981), employ surrealistic images to depict the corruption and lunacy of a politically scarred country. The short-story collections Incidents at the Shrine (1986) and Stars of the New Curfew (1988) portray the essential link in Nigerian culture between the physical world and the world of the spirits.

He has received numerous awards and honours for his literary contributions, including the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and the Crystal Award by the World Economic Forum. Also, Okri won the Booker Prize for his novel The Famished Road (1991), the story of Azaro, an abiku (“spirit child”), and his quest for identity. The novels Songs of Enchantment (1993) and Infinite Riches (1998) continue the themes of The Famished Road, relating stories of dangerous quests and the struggle for equanimity in an unstable land.

Okri’s other novels included Astonishing the Gods (1995); Dangerous Love (1996), about “star-crossed” lovers in postcolonial Nigeria; In Arcadia (2002); Starbook (2007); The Age of Magic (2014); and The Freedom Artist (2019). Okri’s works have been translated into several languages and have gained international acclaim for their lyrical prose and imaginative storytelling. He is recognised as one of Africa’s leading contemporary writers and has influenced a generation of writers with his unique blend of magical realism and social commentary.

Among the recurring themes in Okri’s works are:

- The conflict between the material world and the spiritual world: This is the essence of Okri’s magical realism, where worlds overlap and influence each other, reflecting traditional African beliefs.

- Social and political realities in Nigeria: Despite the fantastical elements, Okri’s works are a scathing critique of corruption, poverty, violence, and the challenges facing post-colonial societies.

- Childhood and Innocence: His novels often feature children who see the world through different eyes, allowing him to explore themes of innocence, loss, and the influence of adults on children’s lives.

- Art and Creativity: Okri is a multi-talented artist (he was a painter before becoming a full-time writer), and themes of art and the role of the artist in society appear frequently in his works.

- The Search for Meaning and Freedom: His characters embark on existential journeys in search of identity, meaning, and liberation from various constraints.

- The Impact of Colonialism and Beyond: His works indirectly address the continuing consequences of colonialism on African identity and the challenges facing the continent in building its future.

- Good and Evil: Okri in-depthly explores the nature of evil and its manifestations in the world, seeking possibilities for happiness in a turbulent world.

- Hope and Renewal: Despite his depiction of injustice and suffering, his works always carry within them the seed of hope for change, renewal, and the ability to overcome adversity.

Okri is among the novelists who have transcended conventional categorisations. His writings go beyond magical realism to touch on existential philosophy, social criticism, and reflections on the nature of art and creativity. Okri has pioneered a new literary form called stoku, a hybrid between the short story and haiku, characterised by its dreamlike quality and intensity. It first appeared in his collection Tales of Freedom.

Some of Okri’s quotes:

“Stories can conquer fear, you know. They can make the heart bigger.”

“The most authentic thing about us is our capacity to create, to overcome, to endure, to transform, to love and to be greater than our suffering.”

“Storytellers ought not to be too tame. They ought to be wild creatures who function adequately in society. They are best in disguise. If they lose all their wildness, they cannot give us the truest joys.”

“The best writing is not about the writer, the best writing is absolutely not about the writer, it’s about us, it’s about the reader.”

“Some people say when we are born we’re born into stories. I say we’re also born from stories.”

“It is not important for me as a writer that you leave a piece of writing of mine with either an agreement or even a resonance with what I have said. What is important is that you leave with the resonance of what you have felt and what you thought in reaction to that.”