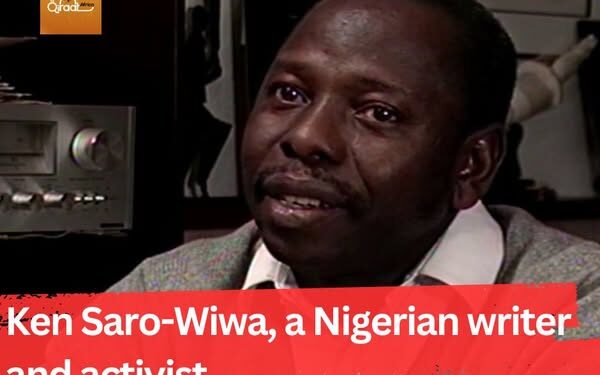

Ken Saro-Wiwa was a Nigerian writer, environmental activist, and television producer born on October 10, 1941, in Buri, Ogoniland, an oil-rich region in the Niger Delta in southern Nigeria. He was educated at prestigious schools in Nigeria, including Government College, Umuahia, and the University of Ibadan, where he studied English language and literature.

After graduating, he briefly taught (as a teaching assistant) at the University of Lagos before joining federal forces in the civil war of the late 1960s. Afterward he worked as a government administrator until 1973, when he left to concentrate on his literary career.

Saro-Wiwa began his literary career in the 1970s, publishing numerous novels, plays, poetry collections, and essays. His writings are often characterized by their satirical and humorous style and address important social and political issues in Nigeria. Among his early works are the novel “Tambari” (1973) and the play “Bride for Mr. B” (1983).

Saro-Wiwa’s achievements in the literary field include his innovative use of language, particularly in “Sozaboy,” where he employs “Rotten English” to depict the chaos and disintegration caused by war. He was also praised for his ability to address pressing social and political issues in Nigeria through his writing, shedding light on the struggles faced by ordinary people, particularly those in the Niger Delta region. In the 1980s, Saro-Wiwa achieved widespread fame in Nigeria through his popular television comedy show, “Basi and Company.” The show was a huge success and delivered humorous social and political criticism.

Saro-Wiwa was known for his outspokenness on environmental issues and his activism against the exploitation of the Ogoni people and their land by the Nigerian government and multinational oil corporations.

Ogoniland, the homeland of the Ogoni people, has been subjected to oil extraction since the late 1950s, resulting in widespread environmental degradation, land and water pollution, and a negative impact on the livelihoods of local people. Saro-Wiwa felt strongly about the injustice done to his people by the exploitation of their region’s resources without fair compensation or respect for the environment.

In 1990, Saro-Wiwa played a pivotal role in establishing the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), a nonviolent grassroots organization dedicated to defending the political, economic, and environmental rights of the Ogoni people. Saro-Wiwa led the movement with passion and intelligence, using his writings, speeches, and public platforms to expose the devastating impact of oil companies’ operations, particularly Shell, on the environment and the lives of Ogoni people.

MOSOP demanded fair compensation for environmental damage, greater sharing of oil revenues, and environmental protection in Ogoniland. The movement organized widespread peaceful demonstrations and gained increasing international support for its cause.

Saro-Wiwa’s activities and the MOSOP movement angered the Nigerian military government and oil companies. In 1994, Saro-Wiwa and several other MOSOP leaders were arrested after the deaths of four Ogoni chiefs at a political rally. In a trial by a special tribunal that was denounced by foreign human rights groups, he was found guilty of alleged complicity in the murders. Saro-Wiwa vehemently denied the charges, and international human rights organizations condemned the trial as a sham and unfair.

Despite widespread international campaigning for his release, Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogoni activists were convicted and sentenced to death. On November 10, 1995, Ken Saro-Wiwa and his companions were executed by hanging, sparking international condemnation and leading to calls for economic sanctions against Nigeria, which was suspended from the Commonwealth a day after the executions.

Ken Saro-Wiwa has become a global symbol of the struggle for environmental justice, minority rights, and freedom of expression. His life and tragic death have profoundly influenced environmental and human rights movements worldwide. His literary and activist legacy continues to inspire new generations of writers and activists.

Shell later announced its commitment to a natural gas project worth nearly $4 billion, one of the largest foreign investments in Nigerian history. In 2009, Shell paid $15.5 million in an out-of-court settlement intended to resolve a lawsuit brought against it in 1996 on behalf of members of Saro-Wiwa’s family and others. Shell, accused in the lawsuit of being complicit in human rights abuses in Nigeria and in the 1995 executions, denied any wrongdoing.

The issues of environmental pollution and social justice that Saro-Wiwa fought for continue in the Niger Delta region today. The Ogoni people continue to struggle for reparations for environmental damage and a more sustainable and just future.

Saro-Wiwa’s selected literary works include Tambari (1973); Bride for Mr. B (1983); Songs in a time of war (1985); Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English (1985); A forest of flowers (1986); Prisoners of Jebs (1988); On a Darkling Plain: An Account of the Nigerian Civil War (1989); Nigeria: The Brink of Disaster (1991); Genocide in Nigeria: The Ogoni Tragedy (1992); A Month and a Day: A Detention Diary (1995); Silence Would Be Treason: Last Writings of Ken Saro-Wiwa (published posthumously in 2013).

Quotes from Saro-Wiwa:

“I’ve used my talents as a writer to enable the Ogoni People to confront their tormentors. I was not able to do it as a politician or a businessman. My writing did it… I think I have the moral victory.”

“The writer cannot be a mere storyteller; he cannot be a mere teacher; he cannot merely x-ray society’s weaknesses, its ills, its perils. He or she must be actively involved in shaping its present and its future.”

“I tell you this: I may be dead, but my ideas will not die.”

“The men who ordain and supervise this show of shame, this tragic charade, are frightened by the word, the power of ideas, and the power of the pen.”

“I have no doubt about the ultimate success of my cause, no matter the trials and tribulations that I and those who believe with me may encounter on our journey. Neither imprisonment nor death can stop our ultimate victory.”

“In this country [England], writers write to entertain; they raise questions of individual existence… But for a Nigerian writer in my position, you can’t go into that. Literature has to be combative.”

“Whether I live or die is immaterial. It is enough to know that there are people who commit time, money, and energy to fight this one evil among so many others predominating worldwide. If they do not succeed today, they will succeed tomorrow.”

“The stories that I tell must have a different sort of purpose from the artist in the Western world… and art, in that instance, becomes so meaningful both to the artist and to the consumers of that art because you do not just depend on them to read your books; you even have to live a life that they can emulate.”