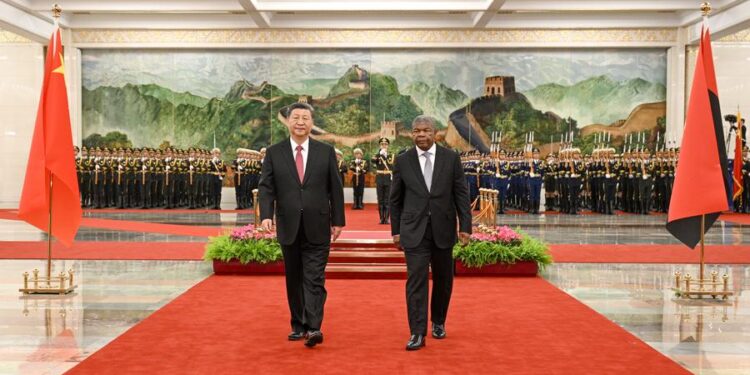

Some years ago, African perspectives on geopolitics took shape as more nations on the continent preferred dealing with China and Russia to dealing with France, America, and others when it came to the area’s economy and social development. Yet, this has materialized into different prospects and threats as some debt-reddened African countries have entered the loan cobweb of the powerful Chinese government spider with a romance of high-profile and gigantic projects all across the continent. Coupled with other interests, such as security in Africa. But the recent visits to China by Angolan President Joao Lourenco have begun to propagate a new economic roadmap based on oil, which is of great benefit to Beijing.

Many believe that Angola, a Portuguese-speaking country in Southwest Africa emerging from a 27-year civil war that ended in 2002, has enjoyed a flourishing partnership with China over the past two decades. This partnership is characterized by cooperation across various fields, and Angola has achieved significant progress in rebuilding the country, industrial modernization, and talent development. Subsequently, Angola attained official independence on November 11, 1975, and, while the stage was set for transition, a combination of ethnic tensions and international pressures rendered Angola’s hard-won victory problematic.

As with many post-colonial states, Angola was left with both economic and social difficulties, which translated into a power struggle between the three predominant liberation movements. After the war, Angola had been wanting help from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. There were so many conditions. Angola was really left with one option: to turn to the Chinese so they could give them the type of financing they needed to rebuild the country.

Before now, the Angolan government has maintained a reform agenda since the 2017 election of President Joao Lourenço. His administration has adopted measures to improve the business environment and make Angola more attractive for investment. Angola’s infrastructure requires substantial improvement, which the government is seeking to address by attracting investment and public-private partnerships to improve and manage ports, railroads, and key energy infrastructure.

Insiders say the country’s system does not allow for diversity of thought and views, equality, peace, and justice. Angola, formerly a market economy, now depends more on oil revenues than most African nations. The country is not an independent economy and has immense glitches in the foreign exchange market, which are affecting foreign direct investment (FDI) as foreign nationals don’t invest much in the country due to government interventions, they argued. Talking about China’s investment in Angola. They noted that the Chinese are just financing Angola for their own prosperity.

Yet, since the end of a thirty-year civil war in 1992, Angola has made significant economic progress. Impressive progress, however, is being made in the reconstruction of Angola’s transport infrastructure, funded mostly by public funds and oil receipts but with significant contributions also from development partners, including the People’s Republic of China in particular but also Brazil. The past year saw Angola experience a year-on-year increase in foreign direct investment inflows of $3.8 billion as of January 2023, according to Angola’s Private Investment and Export Promotion Agency (AIPEX), attributed to efforts in improving regulations, broader economic reforms, improvements in information communication and technology, and infrastructure. The UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2023 indicates that FDI flows to Angola remained negative for the fifth consecutive year in 2022 (-USD 6.1 billion) as companies in the oil sector continued to repay loans.

Experts have indicated that the Angolan conflict was extremely complex, and at least three factors drove it: the Cold War, natural resource rents, and ethnic tensions. After the war in 2002, Angola faces some challenges, such as a deep democratic institution, an economical model, and the reconciliation process. Cabinda was specifically made a part of Angola in 1975, but the Angolan government had to contend with independence movements there until the late 1980s. The region is particularly valuable because a significant amount of Angola’s oil is found there.

In the same way, Angola faces ongoing challenges, including the demands of the enclave of Cabinda. Cabinda has seen political and armed movements advocating for cessation or autonomy, requiring the government to deploy military forces and establish surveillance to maintain unity. The resolution of this conflict and tensions will greatly and positively impact Angola’s economic prospects and stability. Experts are of the opinion that Angola’s future development hinges on its ability to navigate these complex issues and enact meaningful reforms.

Sino-Angolan ties

Though China’s involvement in Angola dates back to the early years of the anticolonial struggle through its support for the three major liberation movements in the country, The relations between Angola and China improved gradually in the 1990s, and Angola became China’s second-largest trading partner in Africa (after South Africa) by the end of the decade, mostly because of defense cooperation. Following the end of the conflict in 2002, China’s relationship with Angola shifted quickly from a defense and security basis to an economic one.

While the Chinese in particular have been improving their bilateral relationship in the geopolitical arena through a series of initiatives and diplomatic strategies for some time now, the China-Africa trade volume has already exceeded $47 billion, and it grew by 13.9% in the first two months of 2024. Also, from January 1 to February 29, China’s exports to Africa increased by 21% to reach $28.78 billion. Similarly, China’s imports from African countries increased by 4.5% to $18.89 billion.

Deeply, China has taken a position contrary to Western governments in its African investment. It characterizes its loans as mutually beneficial cooperation between developing countries, promising not to interfere in the internal politics of those it lends to. As a consequence, in this respect, it presents itself in contrast to Western countries, which are accused by China and some African governments of arrogant, democratic posturing—often by former colonial powers that looted African resources during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Why is China involved in Angola?

There are no doubts that Beijing needs oil and Luanda needs infrastructure, housing, roads, train systems, education buildings, hospitals, and manufacturing plants. Observers say the influence of China in Angola is often overplayed, and there is a growing fatigue among senior Angolan officials about the West’s fixation with China’s engagement in Angola. For the most part, Angolan officials are open about their cooperation with China and candid about not wanting to depend on any one developer or commercial partner. But, in 2021, Angola was the most indebted country to China of any African state. In the same year, 72 percent of all Angola’s oil exports went to China. On the other hand, from Angola’s perspective, the Chinese provide funding for strategic post-conflict infrastructure projects that Western donors do not fund. Chinese financing offers better conditions than commercial loans, lower interest rates, and a longer repayment time. Non-Chinese credit lines that Angola secured in 2004 demanded higher guarantees of oil, with no grace period and with high interest rates.

In contrast to this, China offers Angola a new model of cooperation, while Angola provides China with oil and construction projects. Is there a drawback for Angola? Indeed, the lack of conditionality may put pressure on Angola to improve its governance and transparency while reducing poverty, although it should be noted that there has been no other country in the world where infrastructure development is important. Still, Luanda has been cautious in its approach to the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) with the EU and appears to be conscious of the inherent and associated dangers of trade diversion away from the world reference-priced import source(s) of China in particular. Analysts also indicate that China’s demand and subsequently high oil prices have largely underpinned Angola’s impressive growth rates. Angola and African oil producers in general achieved the largest gains from the most recent commodity supercycle.

– The China-Angola trade

For some years now, Angola has enjoyed a large trade surplus with China. Importantly, Angola’s exports to both China and other destinations in general do not conform to the normal patterns of supply and demand that experts associate with global trade patterns. Thus, China, while able to perhaps influence its share of this trade, has a limited influence over the export quantity of oil from Angola. Data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), an online data visualization and distribution platform focused on the geography and dynamics of economic activities, indicated that in December 2023, China exported $293 million and imported $1.95 billion from Angola, resulting in a negative trade balance of $1.66 billion. Between December 2022 and December 2023, China’s exports decreased by $135 million (-31.5%), from $428 million to $293 million, while imports increased by $161 million (8.99%), from $1.79 billion to $1.95 billion. Both countries signed an investment protection agreement in December 2023. By the same token, Angolan firms, as of December 25, have had tariff-free access to China’s massive consumer market across 98% of goods under a separate agreement.

– Angola’s big debt to China

In the area of financial and economic management, in proximity to the vaunted development agendas in Angola, more important parts of the country are far behind in terms of infrastructural development, for instance, Cabinda. Local media professionals maintained that Cabinda is a problem of the paradox of abundance; while Lunda produces a lot of diamonds, Cabinda produces a lot of oil, and there’s nothing to show for it. In Cabinda, the biggest infrastructure is the governor’s office. As the office of the government is a high rise, it dwarfs everything else around it, they stated. Currently, Angola is the top recipient of Chinese loans in Africa, accounting for around 27 percent of China’s total loans to the continent during 2000–2022. Of the $45 billion Angola has borrowed to date, around 58 percent has been for energy projects. An expert says the problem for Angola is not the level of indebtedness but what they have done with all the money from China. Given the endemic corruption in Angola and the opacity around Chinese projects, there was little supervision or quality control of infrastructure projects.

Change in strategic partnership

Recently, Angola sought financing from Beijing or private investors in China to build a refinery at the port city of Lobito, a petrochemical plant, and a military air force base after both countries announced the elevation of bilateral ties to a comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership on the occasion of a four-day state visit to China by Angolan President Joao Lourenco. Analysts note that a key Angolan policy has been to invest much of the returns from oil exports into infrastructure, in particular through relatively well-negotiated natural resource-based loans with China.

Nevertheless, now that much new infrastructure has been built, the country is trying to diversify its economy. The latest presidential visit confirms that China will remain central to Angola’s plans, for good strategic reasons on both sides. However, the fundamental and inescapable issue of governance remains in Angola. Without being judgmental, experts suggest that efforts to address governance and transparency must be on the table, along with an increased effort to ensure that the benefits of oil wealth are more evenly distributed.

Moreover, the analyst articulates that the Angola-China partnership is characterized by cooperation across various fields, and Angola has achieved significant progress in rebuilding the country, industrial modernization, and talent development. Still, experts argued that it is important and critical that African nations ask China and the West to cooperate on debt distress, ideally speaking with one voice through institutions such as the African Union (AU). As well as China’s massive credit lines to finance infrastructure development, this also raises important questions related to the sustainability of these projects. To conclude, for Angola’s development both socially and economically, the resource-rich country will require transparency, accountability, democratic checks and balances, and public investment in health and education.

ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

This article expresses the views and opinions of the author and does not necessarily reflect the views of Qiraat Africa and its editors.