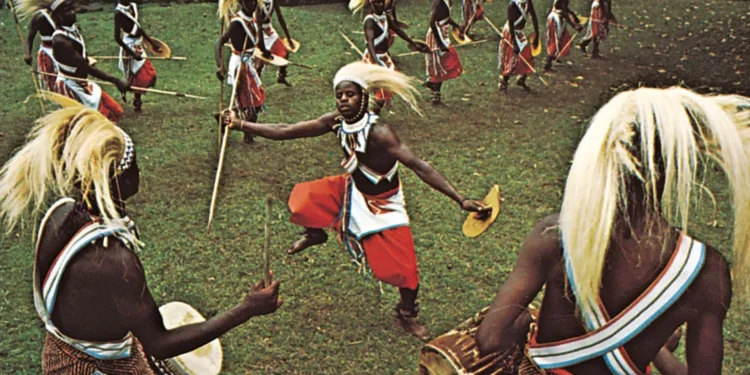

The Tutsi are one of the major ethnic groups in the African Great Lakes region, concentrated primarily in Rwanda and Burundi, with smaller communities in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Tutsi and Hutu belong to the same broader linguistic and cultural group, speaking Kinyarwanda in Rwanda and Kirundi in Burundi. This means that the division between them is not primarily linguistic or religious.

Some anthropologists suggest that the Tutsi are descendants of pastoral groups who migrated to the region from the northeast (possibly from the Horn of Africa or the Nile Valley) centuries ago. This hypothesis posits that they brought cattle with them, a defining characteristic of their traditional culture and economy.

According to 101 last tribes:

“Tutsis are considered to be of Cushitic origin by some researchers, although they do not speak a Cushitic language and have lived in the areas where they are for at least 400 years, leading to considerable intermarriage with the Hutu in the area. Due to the history of intermingling and intermarrying of Hutus and Tutsis, ethnographers and historians have lately come to agree that Hutu and Tutsis cannot be properly called distinct ethnic groups.”

Historically, the classification between Tutsi and Hutu was based more on occupation and economics than on strict biological ethnicity. The Tutsi are traditionally pastoralists with large herds of cattle. This cattle ownership was the foundation of their wealth and social status, while the Hutu are traditionally farmers.

The division between the two ethnic groups has been somewhat fluid throughout history. Sometimes, wealthy Hutus with enough cattle could rise socially to be considered “Tutsi,” or conversely, poor Tutsis who lost their cattle could be “descended” to become “Hutus.”

Before the arrival of European colonial powers, societies in Rwanda and Burundi were organized into complex, centralized kingdoms, with the Tutsi at the top of the social and political hierarchy.

The Kingdom of Rwanda was a relatively unified kingdom ruled by a Tutsi king, known as a Mwami, whose authority was considered divine. The kingdom relied on a network of Tutsi nobles who administered the provinces, collected tribute, and oversaw the army. The Kingdom of Burundi, also a centralized kingdom, was ruled by a king, but its political system was slightly less centralized than Rwanda’s.

The relationship between the Tutsi and Hutu was partly regulated by the Ubuhake system, a system of cattle-based patronage contracts: Tutsi cattle owners provided cattle (or the right to use them) to Hutu in exchange for labor, loyalty, and service. This system reinforced Tutsi social and political dominance, as Hutu depended on the herders for cattle, which were a symbol of wealth and power. This traditional system was complex, as Tutsi social dominance was based on economic and political foundations and was not necessarily a rigid system of racial segregation as it later emerged.

The arrival of European powers, specifically the Germans and then the Belgians (who colonized the region after World War I), marked a disastrous turning point in the relationship between the Tutsi and the Hutu. The Belgian colonial administration excessively exploited and reinforced the division between the two groups. The Belgians relied on the “Hamitic” hypothesis, which posited that the Tutsi (taller and lighter-skinned) were a superior race that had migrated from the north and were therefore closer to the white race and more qualified to rule.

The Belgians also defined “Tutsi” as anyone owning more than ten cows (a sign of wealth) or with the physical feature of a longer nose or longer neck, commonly associated with the Tutsi. They opted for indirect rule, relying on the ruling Tutsi elite to implement their administration. They granted them broad powers and integrated them into the educational and administrative systems, deliberately marginalizing the Hutu.

In the 1930s, the Belgians issued official identity cards that recorded the ethnic affiliation of each citizen (Tutsi, Hutu, or Twa). This measure transformed the flexible social and economic divisions into a fixed and insurmountable ethnic classification, thus permanently entrenching the division.

This long-standing colonial support for the Tutsi elite fueled resentment among the Hutu majority and paved the way for post-independence conflict. As colonialism drew to a close in the late 1950s, the colonial powers began to shift their support abruptly. Belgium, for example, turned to the Hutu nationalist movement, believing that the democratic majority should govern.

Rwanda experienced a violent revolution in 1959, which overthrew the Tutsi monarchy and triggered widespread violence against the Tutsi. Hundreds of thousands of Tutsi fled to neighboring countries (Uganda, Burundi, Congo, and Tanzania). Rwanda became a republic under Hutu rule (led by Grégoire Kayibanda) after independence in 1962.

In Burundi, things initially unfolded differently. The Tutsi monarchy remained in place until it was overthrown in a military coup in 1966. However, the Tutsi elite maintained control of the army, leading to decades of bloody conflict. For example, following a Hutu coup attempt, the Tutsi-dominated army launched a widespread genocide (Burundian Genocide of 1972) against the Hutu elite and intellectuals, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 100,000 to 300,000 people and consolidating Tutsi control over the military and political establishment until the 1990s.

Another conflict was the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, which represents the tragic culmination of a history of tensions exacerbated by colonial and social policies. In April 1994, after the downing of the plane carrying Hutu President Juvenal Habyarimana, Hutu extremist groups (the Interahamwe militia and the Rwandan Armed Forces) began implementing a systematic plan to exterminate the Tutsi. Over the course of approximately 100 days, nearly 800,000 people (according to many reports) were killed, the vast majority of them Tutsis, as well as moderate Hutus who refused to participate.

The Rwandan genocide ended with the intervention of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel force composed mostly of former Tutsi refugees, led by Paul Kagame. The RPF seized control of the country and established a new government.

After 1994, Rwanda and Burundi experienced different attempts to address these divisions. The Rwandan government, now led by Tutsis, focused on building a unified national identity. References to ethnic affiliations (Hutu/Tutsi/Twa) were banned in official documents and public institutions, and it was emphasized that all citizens were “Rwandans.” The traditional justice system, Gacaca, was established to address genocide cases. Despite success in achieving economic and security stability, issues of political freedoms and the integration of former Hutus into the system remain a source of ongoing debate.

Also, Burundi remained plagued by conflict. Following the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement of August 2000, power was formally shared between the Tutsi and Hutu elites (specifically within the military and government) to prevent either side from dominating, but tensions resurface periodically.