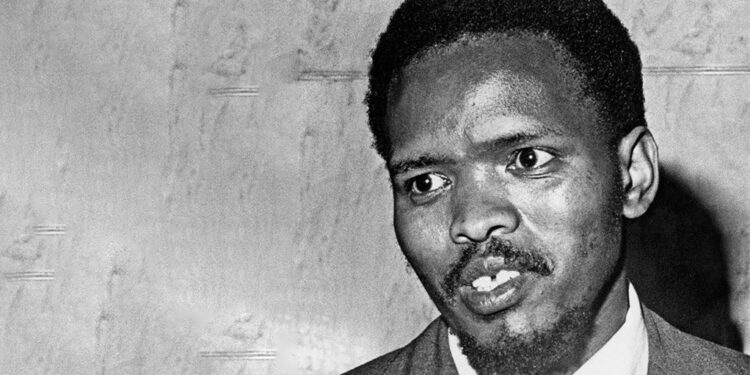

Bantu Stephen Biko was born on December 18, 1946, in King William’s Town, in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. He was raised in a Zulu family; his father was a civil servant and his mother a domestic worker. He received his early education in black schools, where he excelled academically. After completing primary school, he enrolled at Lovedale Institute, a prestigious boarding school, but was expelled along with his brother due to suspicion of their political activities. He completed his secondary education at St. Francis College in Mariannhill, a liberal Catholic institution.

In 1966, Biko enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Natal, in its non-white section. The university environment was the incubator in which his political awareness was systematically formed. During this period, most anti-apartheid political organizations, such as the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), were banned, and their leaders were either imprisoned or in exile. This political vacuum created an opportunity for a new generation of activists, among whom was Biko.

At university, Biko initially became involved with the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), a multiracial student organization dominated by liberal white students. Through his experience with NUSAS, Biko and a number of his black colleagues came to the conclusion that white students, even those sympathetic to the Black cause, were unable to fully understand the experience of racial oppression. They believed that the presence of Black students in white-led organizations reinforced subordination and prevented the development of independent Black leadership.

Based on this perception, in 1968, Biko led the breakaway from the NUSAS and established the South African Students Organization (SASO), an organization exclusively for Black students (in the broad sense of the word, including Coloureds and Indians). Biko was elected its first president in 1969. This organization formed the nucleus from which the Black Consciousness Movement emerged as a philosophy and program of action.

The Black Consciousness Movement was not merely a political organization; it was, at its core, a philosophy aimed at redefining Black identity. Biko’s ideas, expressed in his writings under the pseudonym “Frank Talk” in the organization’s magazine, were based on several fundamental principles:

Psychological liberation first: Biko believed that the most powerful weapon in the hands of the apartheid regime was not military force or oppressive laws, but rather its ability to instill feelings of inferiority and inadequacy in Black people. Therefore, the first step toward physical and political liberation was psychological liberation. He called on Black people to shed their inferiority complex, reject the definitions imposed on them by white society, and embrace their skin color, history, and culture.

Definition of “Black”: The movement provided a comprehensive political definition of the term “Black,” extending beyond Africans to include all those categorized by the regime as “non-white” and persecuted on the basis of race, including Coloreds and Indians. The goal was to build a united front of all oppressed groups.

Rejecting White Liberalism: Biko criticized the role of white liberals in the struggle movement, arguing that, whether intentionally or unintentionally, they tended to impose their patronage on Black activists and determine the pace and objectives of the struggle to suit their own interests. He emphasized the need for Black people to lead their own struggle without external interference.

Self-Reliance: The movement called for the development of independent Black community institutions and projects to reduce dependence on white-controlled infrastructure. This included health, education, and economic programs aimed at serving Black communities and strengthening their resilience.

After establishing the intellectual and organizational base of SASO, Biko worked to expand the influence of the Black Consciousness Movement beyond the universities. In 1972, he co-founded the Black People’s Convention (BPC), an umbrella organization of more than 70 religious, cultural, and political associations that embraced Black Consciousness thought. The convention aimed to coordinate efforts at the national level and implement self-reliance programs.

Through this platform, the Black Community Programmes (BCP) were launched, the operational arm of the movement. These projects established mobile health clinics, trust funds, and craft projects in Black townships. The goal of these initiatives was not only to provide essential services but also to demonstrate the ability of Black people to manage their own affairs and build strong, independent communities.

Because of his growing activism, Biko became a prime target for the apartheid regime’s security services. In 1973, the government decided to impose a “banning order” on him. Under this order, his movements were restricted and he was prohibited from leaving his hometown, King William’s Town. He was also prohibited from speaking to more than one person at a time, from speaking publicly or writing for publication, and his quotes were prohibited. Despite these strict restrictions, Biko continued his activism in secret, organizing community projects and communicating with his fellow members of the movement.

Between 1975 and 1977, Steve Biko was arrested four times and detained for several months without trial. On August 18, 1977, he was arrested for the last time at a police checkpoint outside King William’s Town and detained under Section 6 of the Terrorism Act, which allowed for indefinite detention without trial.

Biko was taken to the Security Police headquarters in Port Elizabeth, where he was interrogated and tortured for several days. During the interrogation, he sustained severe head injuries that led to brain damage and a coma. On September 11, 1977, the police decided to transfer him to a prison hospital in Pretoria, more than 1,100 kilometers away. He was transported naked in the back of a Land Rover, without any medical care.

On September 12, 1977, Steve Biko died alone on the floor of his cell in Pretoria Prison. Authorities declared the cause of death to be a hunger strike. This account was widely rejected and skepticized both locally and internationally. The white liberal journalist Helen Zille, who later became a prominent politician, played a role in uncovering the truth through her sources, sparking a global uproar. An autopsy later revealed that Biko died as a result of severe brain injuries caused by blunt force trauma to the head.

Biko’s death sparked widespread outrage. His funeral was attended by over 20,000 people, including foreign diplomats, and turned into a massive political demonstration. Internationally, his death increased pressure on the apartheid regime, and the United Nations Security Council imposed a mandatory arms embargo on South Africa.

A month after his death, the government banned 18 organizations associated with the Black Consciousness Movement, including SASO and the BPC, in an attempt to crush the movement.

Steve Biko’s influence was profound and lasting. His greatest contribution was his success in changing the psychological state of an entire generation of Black people in South Africa. The Black Consciousness Movement restored dignity and self-confidence to Black people, encouraging them to challenge the status quo not only politically but also culturally and psychologically.

The ideas of the Black Consciousness Movement are believed to have been the primary driving force behind the 1976 Soweto schoolchildren’s uprising, which erupted in protest against the imposition of Afrikaans (the language of white settlers) as the language of instruction. This uprising marked a turning point in the struggle against apartheid.

After his death, Biko became a global symbol of resistance against injustice and oppression. His story has inspired numerous artists and activists around the world, such as the song “Biko” by British musician Peter Gabriel and the film “Cry Freedom” by Richard Attenborough.

Biko’s ideas on identity, psychological liberation, and self-reliance remain relevant in contemporary South Africa, where debates about racial equality, economic justice, and the legacy of apartheid continue.