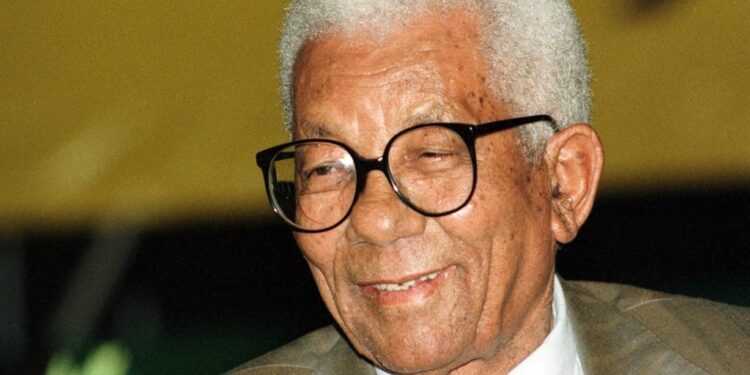

Walter Sisulu is considered one of the most pivotal figures in modern South African history for his leadership of the African National Congress (ANC) and his strategic role as an architect of the transformations within the struggle against apartheid. His career was characterized by working behind the scenes, where he was known for his ability to organize and connect different generations within the political movement.

Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu was born on May 18, 1912, in the Ngcobo area of the Transkei province (now Eastern Cape). His family background reflected the complexities of South African society; he was the son of a Black mother who worked as a domestic servant and a White father who worked as an official in the railway authority.

Sisulu did not have the same extensive educational opportunities as his peers, such as Nelson Mandela or Oliver Tambo, leaving school after completing primary education to support his family. He worked various demanding jobs, including working in the gold mines of Johannesburg, working in dairy factories, and working in bakeries.

These early working experiences helped shape his class and political consciousness, as he came into direct contact with the suffering of Black workers and the systemic discrimination in wages and working conditions.

Sisulu joined the African National Congress (ANC) in 1940. Within a few years, he became the driving force behind the party’s transformation from a traditional negotiating organization into a radical mass movement.

In collaboration with Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, and Anton Lembede, Sisulu helped found the ANC Youth League. The League aimed to inject new blood into the party and demand that the old leadership adopt more assertive tactics, such as strikes and civil disobedience, instead of simply sending petitions and engaging in diplomatic protests.

In 1949, Sisulu was elected Secretary-General of the ANC. In this role, he oversaw the 1952 Defiance Campaign, the first coordinated national movement against apartheid laws. Sisulu was the organizational mastermind who managed the logistics of these actions, making him a direct target of the regime’s security services.

As the regime’s repression intensified in the 1950s, Sisulu and his colleagues began to reassess their strategy of nonviolence. In 1953, he embarked on a clandestine trip that included the Soviet Union, several Eastern European countries, and China. This trip proved pivotal, as he began to view armed struggle and an alliance with the Communist Party as essential options for confronting the police state.

Sisulu participated in founding Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC), and participated in planning sabotage operations against government facilities.

In July 1963, police raided Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, where Sisulu and other leaders were hiding. They were tried in what became known as the Rivonia Trial. He faced charges of sabotage and conspiracy to overthrow the government. In 1964, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. He spent 25 years in prison, most of it on Robben Island with Mandela. During his imprisonment, he was seen as the “father figure” of the prisoners, renowned for his ability to resolve conflicts between different political factions within the prison and maintain the morale of his fellow inmates.

Sisulu was released in October 1989, months before Mandela, as the apartheid regime began to unravel under international and domestic pressure. Despite his advanced age and declining health, he played a vital role in negotiations, as he participated in preliminary talks with Frederik Willem de Klerk’s government to dismantle the apartheid regime.

He worked to reorganize the ANC’s offices within the country after the lifting of the ban and was elected Deputy President of the ANC in 1991 and remained in this position until 1994.

Historians describe Sisulu as a “kingmaker.” While Mandela possessed charisma and oratorical skill and Tambo international diplomatic acumen, Sisulu was the organizational link that held the threads together. Sisulu did not seek high-ranking government positions after the 1994 elections. He was also a firm believer in the necessity of an alliance between different races (Blacks, Coloureds, Indians, and progressive Whites) to confront apartheid, which was embodied in the “Freedom Charter” of 1955.

Walter married Albertina Sisulu in 1944, who would later become a prominent symbol of the struggle in her own right. The couple, Walter and Albertina Sisulu, exemplified family resilience in the face of persecution and long imprisonment.

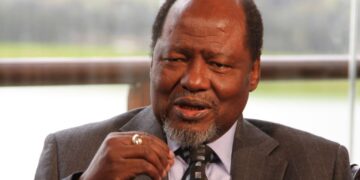

Walter Sisulu died on May 5, 2003, shortly before his 91st birthday. He left behind a legacy as one of the key architects of South Africa’s democratic future.

The rise of Nelson Mandela as a global icon cannot be understood without recognizing the role Sisulu played in introducing, discovering, and guiding him in his early years. Sisulu represents the practical and organizational side of revolution, the aspect often overshadowed by charismatic figures, yet the essential driving force behind any radical political change.

Selected Quotes from Walter Sisulu

“The fundamental principle in our struggle is equal rights for all in our country, and that all people who have made South Africa their home, by birth or adoption, irrespective of colour or creed, are entitled to these rights.”

“It is the job and task of all democrats, where ever we are located to advance this idea: That nothing short of full freedom will satisfy us.”

“You are called upon to intensify your campaign in the fight for freedom and to build the most powerful organisation and to produce even more efficient leadership, even more Illustrious Sons of the Soil than those I have already mentioned. You are called upon to recruit our fine youth and women for the struggle in a manner never before achieved.”

“Once our people understand the Charter and its significance, the attainment of economic and political power in our lifetime – nothing can stand in the way of making its demands a reality.”

“It would, however, be very wrong to imagine that we will do exactly what was done in 1913; and not to realise that times are different, and that the methods of the oppressor are not exactly the same as they were in the past.”