At the end of the 19th century, European powers partitioned Africa in a frenzy of colonization known as the “Scramble for Africa.” Today, a new form of competition is unfolding—less overtly colonial but equally consequential. Global powers such as China, the United States, Russia, and former colonial nations like France are vying for influence across the continent through infrastructure investments, military partnerships, and strategic diplomacy. This modern contest is reshaping Africa’s geopolitical landscape and raising critical questions about sovereignty, development, and the balance of power in the 21st century.

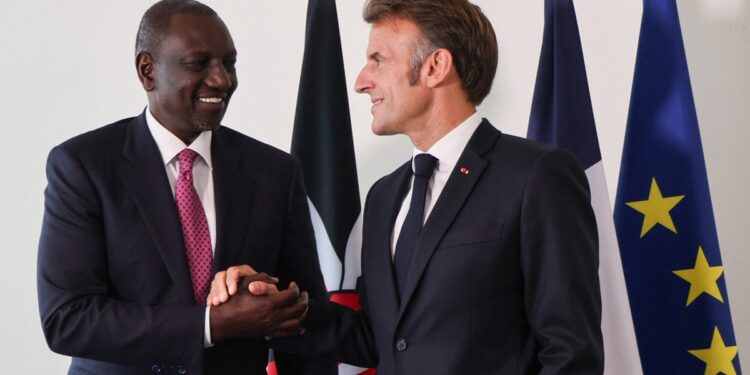

Africa has been a central part of President Emmanuel Macron’s foreign policy from the start of his tenure. This was motivated by Macron’s perception that a large number of global challenges with implications for France are concentrated in Africa (climate change, demography, terrorism, economic development, and health). Macron has put a good deal of energy into reshaping the France–Africa relationship and building a new narrative. He drew on France’s foreign policy levers and made many positive announcements, but it remains difficult to point to concrete achievements.

France has legitimate interests in Africa that it would like to promote through a partner-based approach founded on transparency and reciprocity. That is the focus of the speech President Macron gave on 28 November 2017 at University Ki-Zerbo in Ouagadougou. He set out a series of detailed commitments for forging a new relationship and a new outlook for France and Africa.

Unfortunately, France’s influence in its former African colonies—known by the term Françafrique—has seriously declined in recent years. Military coups in the Sahel—such as in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger—have led to the expulsion of French troops and the cancellation of military agreements. These coups have often been driven by explicitly anti-French sentiment and involved the open embrace of France’s adversaries, such as Russia.

More than a decade of insurgencies in the Sahel have displaced millions and engendered economic collapse, with violence pushing further south towards West Africa’s coast. While controversy has also centered on perceived remnants of French colonial control—such as through the use of the CFA franc, which requires former colonies to deposit at least 50% of their foreign reserves with the French Treasury in Paris.

Finding itself on the back foot, French diplomacy has shifted its focus to English- and Portuguese-speaking African countries—countries (Anglophone) with no colonial history with Paris and whose dynamic domestic markets offer significant opportunities for French companies. On November 20, 2025, Emmanuel Macron started a five-day African tour covering Mauritius, South Africa, Gabon, and Angola. The aim is to renew partnerships, promote youth and economic initiatives, and strengthen cooperation after France’s setbacks in the Sahel.

This article will not focus on the Macron trip to Africa, but it will briefly explore the drivers of the pivot, its geopolitical and economic rationale, detailed country-by-country dynamics (Nigeria and Kenya), and the broader risks and opportunities. The final section offers political and economic implications of the shift for both France and African states.

Economic Opportunity: Dynamic Markets and Investment Potential

Since 2022, France has pulled its soldiers out of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger after military coups brought in leaders hostile to the French presence. Chad—a linchpin of the West’s war against jihadists in the Sahel—abruptly ended its security cooperation pact with its former colonial master in November.

Analysts suggest that these events in the Sahel have not only diminished France’s diplomatic and political clout on the continent but also contributed to declining commercial success in Africa as well. In banking, for example, Crédit Agricole, BNP Paribas, and Société Générale have all withdrawn from the African market in the last few years—with the higher geopolitical risks a key reason for this.

Paris’s pivot towards English-speaking Africa signals Macron’s desire to reverse the country’s declining influence on the continent, with visits to Nigeria in 2018, Ethiopia in 2019, and South Africa in 2021. “This is not a new trend … but the crises in the Sahel have accelerated this dynamic,” said Togolese economist Kako Nubukpo. Now, “France’s leading trading partners in Africa are not French-speaking,” Nubukpo said.

A key partner in this change of strategy is Nigeria, with its 220 million inhabitants, whose President Bola Tinubu was received by Macron in a grand state visit just one year ago. In 2024, Africa’s most populous country became France’s leading economic partner in sub-Saharan Africa.

Laurent Favier, consul general of France in Lagos, noted that as part of the deep cooperation and relationship between both countries, over 14,000 Nigerians are employed by over 100 French companies that operate across the country today. These firms operate in crucial areas like oil and gas, agriculture and agri-food, pharmaceuticals, renewable energy, technology, logistics, and microfinance, he said.

According to Favier, they make investments in factories, farms, and vocational training institutes and establish long-term partnerships that exemplify their entrepreneurial drive and a strong commitment to social impact.

France still holds significant sway despite competition from China, India, and Turkey, said Alain Antil, a researcher in sub-Saharan Africa at the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI). This is especially true in English-speaking countries where France “is not held back by its colonial past,” he told AFP.

And with urbanization and an emerging middle class, countries throughout Africa are seeking to take advantage of French investment to boost economic growth. “Between 2020 and 2050, there will be between 600 and 700 million more urban dwellers in Africa,” said Antil, adding, “It’s transforming African societies and cities,” which need to be built and equipped to manage the change.

Country Case Studies—Nigeria and Kenya

In 2025, senior French officials explicitly signaled that “West Africa’s security woes are no longer France’s concern,” underscoring the end of large-scale French intervention as a standard security provision. Africa and defense specialist Jonathan Guiffard, of Institut Montaigne, said France cannot afford to abandon all ties in West Africa but may need to reduce its military presence. “France will keep ties with these countries but will have to leave Chad, as the fallout is too deep,” he said.

Similarly, experts agree that France needs to rebuild its African partnerships with less focus on military interventions. Antoine Glaser, a specialist on African politics, said France’s reliance on security pacts was anachronistic. “France must recognize that it has remained present for too long by replacing African armies in terms of security,” Glaser told RFI.

Vircoulon said the historical reasons for France’s military presence in Africa have largely disappeared. “Instead of demilitarizing the relationship, the French government is trying to invent a new model of military partnership that is politically risky,” he said.

- Nigeria

Nigeria and France have enjoyed diplomatic relations since October 1, 1960, with strong collaboration in areas such as counter-terrorism, trade, and cultural exchange. Nigeria is France’s largest trading partner in sub-Saharan Africa and one of the largest global suppliers of hydrocarbons. In the meantime, US president Donald Trump has threatened to intervene militarily in Nigeria over what he called a targeting of Christians. Children and adults from Muslim schools and mosques are, however, also frequently victims of kidnappings.

Economy: With about €4.9 billion in trade, available data indicates that in 2024, Nigeria is France’s top trading partner in sub-Saharan Africa. Also, the West African nation reportedly receives roughly 60% of France’s total investments in the region. This shows that the country is the principal destination of the French capital in West Africa.

Through over 100 French companies operating across sectors including agriculture, infrastructure, services, and manufacturing, more than 14,000 Nigerians are employed.

During a state visit in 2024 by President Bola Tinubu to Paris, Nigeria and France signed infrastructure- and finance-related accords amounting to €300 million, aimed at sectors like healthcare, transportation, agriculture, renewable energy, and human capital development. Besides, Nigerian banks such as Zenith Bank have begun operations in Paris, reflecting a two-way financial integration between the countries.

In addition, Nigeria recently signed a landmark cooperation agreement with France to accelerate the digital transformation of Nigeria’s tax administration, boost cross-border enforcement, and strengthen institutional capacity. Officials say the enhanced collaboration is expected to deepen transparency, improve enforcement frameworks, and position Nigeria’s tax system for greater operational efficiency.

Security: Earlier in December 2025, Nigerian President Bola Tinubu sought more help from France to fight widespread violence in the north of the country. The Nigerian government has said it welcomes help to fight insecurity as long as its sovereignty is respected. France has previously supported efforts to curtail the actions of armed groups, the U.S. has shared intelligence and sold arms, including fighter jets, and Britain has trained Nigerian troops.

Meanwhile, French President Emmanuel Macron, according to media reports, has also affirmed France’s support, stressing that French assistance will come in the form of training, intelligence sharing, and support to affected populations.

- Kenya

Kenya’s relative stability over the years is in stark contrast with most of its neighbors. Somalia, Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Rwanda have all been at various times convulsed by violent conflict far worse than anything Kenya has experienced. Political violence has played out in different manners throughout Kenya’s history. In East Africa, Kenya as a country is one of the examples that shows how France aims to expand its footprint beyond West Africa through regional integration and new sectors.

Diplomatic Re-orientation and Symbolism: French leadership emphasizes the intention to establish “balanced partnerships” with African countries, based on mutual respect rather than the paternalistic relations that were typical of the colonial and post-colonial eras. In Kenya, an East African economic powerhouse, France has strengthened its commercial presence, with the number of French companies operating in the country almost tripling from 50 to 140 in a decade. But a huge trade imbalance in favor of the European nation has cast a shadow on their relations, observers indicated.

France’s turning towards English-speaking Africa is a way to change its continental posture. The proposal to hold the next Africa–France Summit in Nairobi in 2026—marking the first time the summit will take place in a non-Francophone country—is a very symbolic gesture. Officials say this summit will focus on solutions to challenges related to climate, environment environment,and the reform of the international financial architecture, in favorenvironment, of which the two heads of state are strongly mobilized.

It will seek to foster a constructive form of multilateralism, in line with the Paris Pact for People and the Planet and the Nairobi Declaration, which resulted from the Africa Climate Summit. Adding that, this will bring together both political authorities from the African continent and representatives from civil society and the private sector. Meanwhile, the change indicates to the world powers and investors that France still has a deal with Africa, but it is under a modern equal partnership framework and not the old neo-colonial practices. This means that African countries increasingly have options as to which nations they decide to partner with—a trend that, at least in theory, should optimize their chances of extracting maximum value from those relationships.

Economy: African countries are the primary recipients of French bilateral assistance, totalling 40% (€2.7 billion) in 2019, including 29% (€2 billion) for sub-Saharan Africa. In Kenya, an East African economic powerhouse, France has strengthened its commercial presence, with the number of French companies operating in the country almost tripling from 50 to 140 in a decade. But a huge trade imbalance in favor of the European nation has cast a shadow on their relations.

In 2024, Team France developed a new solidarity investment strategy focused on 4 thematic priorities—Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Climate and Renewable Energy, Infrastructure, and Health—identified through a consultative process involving a large number of stakeholders and beneficiaries.

This strategy aims to foster partnerships with Kenya and leverage both Kenyan and French private sectors in order to support the youth and their access to a sustainable society. From renovating hospitals and schools to building dams and electric lines, while supporting education and research for youth and entrepreneurs, France has supported more than 150 projects across Kenya since 2015, for a total investment of 1.8 billion euros.

In November, the French Chamber of Commerce in Kenya hosted the 3rd Edition of French Week 2025, a three-day event featuring discussions, roundtables, and presentations aimed at strengthening Kenya–France trade ties and creating new investment opportunities. The report said the event brought together French and Kenyan companies to showcase projects, innovations, and expertise across sectors including energy, healthcare, infrastructure, retail, and skills development. While key discussions focused on AI and digital innovation, sustainable infrastructure, and the role of trade, tourism, and culture in driving economic and social growth.

The French embassy in March 2025 noted that France ranks among Kenya’s top three bilateral official financiers and top 5 private investors, with more than 120 French companies already operating in Kenya, creating 36,000 direct jobs. Experts indicate that this reflects France and the EU’s shared priorities and commitment to supporting Kenya’s economic growth, youth training, environmental protection, and leadership in renewable energy.

Likewise, among the projects in Kenya financed and/or supported by France are the Kigoro Water Treatment Plant and Northern Collector, which is financed through Agence Française de Développement and is expected to boost water supply in Nairobi. Also, the National System Control Center, which is aimed at enhancing the national grid stability and renewable energy integration, is fully financed by the Direction générale du Trésor and AFD. France is also supporting high education and youth employment through the AFD-funded engineering and science complex of the University of Nairobi, fostering ongoing French-Kenyan academic cooperation.

Looking Foward

Without doubt this is an important turning point for Paris’ foreign policy as well as the course of African geopolitics, economics, and development is France’s move toward anglophone Africa. This shift presents genuine opportunities for Nigeria, Kenya, and other countries such as infrastructure, investment, collaboration, and the revitalization of outside alliances.

At present, Nigeria has an opportunity to play a diplomatic role in bridging the gap between France and its former allies. Strengthening its engagement with West African nations and fostering new security partnerships will be essential in mitigating the threats posed by the shifting geopolitical landscape. Additionally, investing in border security measures and intelligence-sharing mechanisms will be crucial in preventing further instability from spilling into Nigerian territory.

For Nigeria, this French pivot could close a long-standing gap in external security cooperation that is offering supplementary capacity in intelligence, training, and perhaps logistics. Meanwhile, sustained French investment and involvement in infrastructure, energy, finance, and agribusiness could support Nigeria’s developmental agenda, especially if projects align with wider regional economic integration, for instance under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

However, Nigeria should try to guide against overdependence on foreign capital or foreign-driven projects that do not sufficiently build local capacity. As noted in recent research, foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa, if poorly structured, can deepen external dependency and hamper domestic industrialization. Scholars argue that the predominance of extractive and service-oriented capital inflows has deepened external dependency, weakened domestic value chains, and contributed to premature deindustrialization across parts of the continent. Africa’s continued difficulty in attracting manufacturing-oriented FDI—relative to peer emerging economies—constitutes a critical constraint on its economic growth and deeper integration into the global economy.

Analysts noted that though the intentions are clear, there are challenges: competition from other global powers such as China, the US, and the Gulf States, who are anxious to invest in East Africa. For instance, Kenya’s own balancing act between different partners; and the risk that French investments may replicate patterns of dependency if local capacity-building is not prioritised. As analyses of recent FDI flows to Africa show, much foreign investment tends to be service- or extractive-sector oriented which are not always supportive of long-term industrialization.

Kenya occupies a strategic position in East Africa, focal point in regional stability, and contributes to global security efforts, including counterterrorism. Its security institutions play integral parts in human security and development. Ethnic-based violence striking from political interests coupled with post-election uncertainty has greatly impacted Kenya’s national security. This is equally evident at the present times, where anti-governmental youth led protests that began peaceful protests but turned violent.

As Kenya navigates its complex security landscape, the question comes up whether Kenya’s ability to address internal and external threats will maintain while facing new and complex challenges. Furthermore, having a closer look at the political and economic dependencies that go hand in hand with Kenya’s foreign engagements is deeply necessary. How will those dependencies influence Kenya’s political agenda during the next couple of years and is Kenya’s capable of sticking to the responsibilities that are coming up as a consequence of those dependencies.

Ultimately, if successful, France could change its image from that of a former colonial power holding onto power through military presence to that of a contemporary, multifaceted continental partner that combines investment, diplomacy, soft power, tech, and green-economy cooperation.

Looking Forward

Without doubt this is an important turning point for Paris’ foreign policy as well as the course of African geopolitics, economics, and development: France’s move toward Anglophone Africa. This shift presents genuine opportunities for Nigeria, Kenya, and other countries, such as infrastructure, investment, collaboration, and the revitalization of outside alliances.

At present, Nigeria has an opportunity to play a diplomatic role in bridging the gap between France and its former allies. Strengthening its engagement with West African nations and fostering new security partnerships will be essential in mitigating the threats posed by the shifting geopolitical landscape. Additionally, investing in border security measures and intelligence-sharing mechanisms will be crucial in preventing further instability from spilling into Nigerian territory.

For Nigeria, this French pivot could close a long-standing gap in external security cooperation that is offering supplementary capacity in intelligence, training, and perhaps logistics. Meanwhile, sustained French investment and involvement in infrastructure, energy, finance, and agribusiness could support Nigeria’s developmental agenda, especially if projects align with wider regional economic integration, for instance, under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

However, Nigeria should try to guard against overdependence on foreign capital or foreign-driven projects that do not sufficiently build local capacity. As noted in recent research, foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa, if poorly structured, can deepen external dependency and hamper domestic industrialization. Scholars argue that the predominance of extractive and service-oriented capital inflows has deepened external dependency, weakened domestic value chains, and contributed to premature deindustrialization across parts of the continent. Africa’s continued difficulty in attracting manufacturing-oriented FDI—relative to peer emerging economies—constitutes a critical constraint on its economic growth and deeper integration into the global economy.

Analysts noted that though the intentions are clear, there are challenges: competition from other global powers such as China, the US, and the Gulf States, who are anxious to invest in East Africa. For instance, Kenya’s own balancing act between different partners and the risk that French investments may replicate patterns of dependency if local capacity-building is not prioritized. As analyses of recent FDI flows to Africa show, much foreign investment tends to be service- or extractive-sector oriented, which is not always supportive of long-term industrialization.

Kenya occupies a strategic position in East Africa, is a focal point in regional stability, and contributes to global security efforts, including counterterrorism. Its security institutions play integral parts in human security and development. Ethnic-based violence striking from political interests coupled with post-election uncertainty has greatly impacted Kenya’s national security. This is equally evident at the present time, where anti-governmental youth-led protests began as peaceful protests but turned violent.

As Kenya navigates its complex security landscape, the question comes up whether Kenya’s ability to address internal and external threats will be maintained while facing new and complex challenges. Furthermore, having a closer look at the political and economic dependencies that go hand in hand with Kenya’s foreign engagements is deeply necessary. How will those dependencies influence Kenya’s political agenda during the next couple of years, and is Kenya capable of sticking to the responsibilities that are coming up as a consequence of those dependencies?

Ultimately, if successful, France could change its image from that of a former colonial power holding onto power through military presence to that of a contemporary, multifaceted continental partner that combines investment, diplomacy, soft power, tech, and green-economy cooperation.