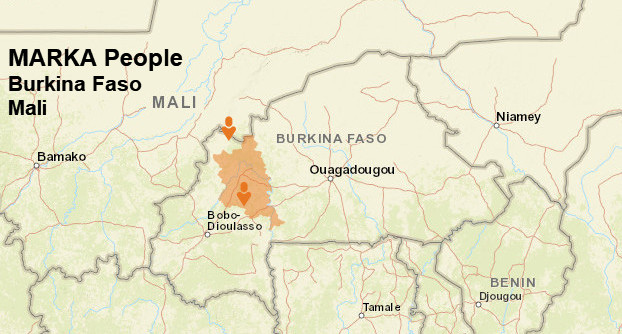

The Marka (or Marka Dafing, Meka, or Maraka) are an ethnic group that primarily concentrated in Mali and Burkina Faso. Their identity is divided between two main categories: the Maraka (often associated with Soninke traders in Mali) and the settled Marka Dafing of Burkina Faso.

The Marka are geographically concentrated in vital areas at the crossroads of trade and agriculture. In Mali, they are found extensively along the Niger River. In this context, the Marka are often referred to as a distinct trading class, heavily influenced by Soninke and Mandinka culture. Historically, they played a prominent role in the trade networks connecting the north (across the Sahara) to the south.

In Burkina Faso, they are concentrated in the west and center of the country, particularly in areas near the Black Volta River. This group is known for its strong ties to agriculture and handicrafts and possesses relatively independent cultural and linguistic characteristics, although influenced by Mande languages.

Linguistically, the Marka are classified within the Mande language family. They speak a language closely related to Bambara and Dioula. However, there are also Marka groups in Burkina Faso who speak Gur (Fulani) languages, indicating extensive cultural and linguistic assimilation and integration over the centuries.

The economic performance of the Marka is characterized by a history of functional specialization, which distinguished them from being simply a traditional agrarian society. The merchant class (in Mali) emerged as prominent trade intermediaries. They controlled a large part of the salt and gold trade, linking the Islamic centers in the north (Timbuktu and Djenné) with the agricultural markets in the south. This commercial role required a high level of trust and transregional networks, as well as their skill in accounting and risk management.

The Marka-Daffin groups in Burkina Faso are renowned for their craftsmanship, particularly weaving and dyeing, as they are among the leading producers of hand-dyed cotton fabrics using natural dyes, especially indigo. These textiles were a vital element of regional trade. Blacksmiths also constituted a specialized and important class. Their role was not limited to crafting agricultural tools and weapons; they also played a ritual and spiritual role in some communities.

Besides, despite their commercial and artisanal dominance, the Maraka practiced agriculture, particularly rice and sorghum cultivation, to ensure food self-sufficiency. The Maraka played a vital role in the spread and consolidation of Islam in West Africa. Their strong commitment to Islam was directly linked to their professions as traders and scholars (centers of learning).

Trade was a major factor in the Maraka’s embracing of Islam. Traveling long distances required belonging to a vast Islamic network that ensured security and trust in commercial transactions, which led to the emergence of a class of religiously educated traders who contributed to the construction of mosques, Quranic schools, and centers of learning in cities such as Djenné and San.

In Mali, where the Marka were primarily traders, their social structure was largely hierarchical. The Nobles (political/scholarly) comprise merchant families and religious families (Marabouts) with significant economic and social influence. The Artisans (Middle Class) comprise blacksmiths, carpenters, and others. While the slaves/sons of slaves represent the lowest rung, and they performed manual and agricultural labor.

Despite this structure, the Marka were characterized by their ability to integrate socially with their neighbors. In Burkina Faso, they maintain close and reciprocal relations with the Mossi people, while in Mali, they are deeply intertwined with the Soninke and Bambara.

Also, certain Marka groups, particularly in rural Burkina Faso, have preserved some spiritual traditions and rituals dating back to pre-Islamic times. These traditions are primarily manifested in the expressive arts, such as the wooden masks, the production and crafting of which the Marka-Daffing in Burkina Faso are particularly known for. Their masks are characterized by abstraction and geometric carvings, with a combination of animal forms (such as antelopes) and human features.

Secret societies played a social, educational, and organizational role, especially in areas where political power was not fully centralized. These societies were responsible for training and teaching young people the rules of social conduct and morality.

The Marka people today face challenges stemming from economic, environmental, and political changes in the region. The advent of modern transportation (trucks and airplanes) and the growth of global trade have weakened the Marka’s traditional role as trade intermediaries in the savanna. Many traders have been forced to adapt to a more modern trading model or turn to agriculture.

Desertification and the degradation of agricultural land in the savanna regions of Mali and Burkina Faso have impacted the Marka’s agricultural and livestock base, increasing pressure on limited resources and forcing some to migrate to urban centers.

The instability and security conflicts that have plagued the Sahel region, particularly central Mali and northern Burkina Faso, have displaced many populations and disrupted traditional trade networks. This has especially affected communities living along major trade routes.

However, despite the challenges, the Marka’s legacy remains rich. Through their role as spreaders of Islam and as trade intermediaries, they contributed to the integration of West Africa into global trade networks during the Middle Ages. Their art, particularly mask making and textiles, is a significant element of West Africa’s global artistic heritage. Their story exemplifies how economic interests, religious transformations, and local culture intertwine to forge a unique and powerful ethnic identity.