The W-Arly-Pendjari Complex, commonly known as the WAP, is the largest and most important protected ecosystem in West Africa. Spanning three countries—Benin, Burkina Faso, and Niger—this transboundary complex represents the last stronghold of the wildlife that once dominated the West African savanna. Recognized for its exceptional ecological value, the complex has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, becoming a symbol of regional cooperation in nature conservation.

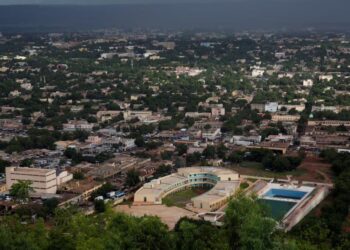

The complex comprises three main interconnected areas that form a continuous ecological fabric, covering an area of over 31,000 square kilometers:

- W National Park: This park takes its name from the meandering shape of the Niger River, which resembles the letter “W.” The park is distributed across the three countries and constitutes the largest part of the complex. It is characterized by its diverse topography, which includes floodplains, rocky hills, and savanna forests.

- Arly National Park: Located entirely in Burkina Faso, it occupies the central part of the complex. It is renowned for its rich vegetation diversity and wetlands, which serve as a haven for migratory birds and numerous large mammals during the dry season.

- Pendjari National Park: Located in northern Benin, it is currently the most protected and managed area within the complex. Thanks to partnerships with international organizations such as African Parks, Pendjari has become a successful model for restoring ecological balance and revitalizing ecotourism in the region.

The global value of the W-Arly-Pendjari Complex lies in its status as the last remaining and most vibrant population of critically endangered species in West Africa. The area is home to the largest remaining population of the West African lion, a critically endangered subspecies. These lions possess genetic and behavioral characteristics that distinguish them from their counterparts in East and Southern Africa.

The area also boasts the largest elephant population in West Africa. These herds move freely across the international borders between the three countries, constantly searching for water and grazing land. Similarly, the area is one of the very few places in West Africa where the cheetah can still be found, although sightings are rare due to its isolated nature.

In addition to the large animals, the area is home to more than 450 bird species, making it a world-class destination for birdwatchers. Its rivers (the Niger, Pendjari, and Mekro) teem with hippos, Nile crocodiles, and countless species of freshwater fish.

The WAP complex plays a vital role in regulating the local climate and protecting water resources in the Sahel and Sudan region. The forests and green spaces within the complex act as natural filters, preventing soil erosion and protecting water quality in the Niger River and its tributaries, resources upon which millions of people depend for agriculture and fishing.

The vast areas of trees and grasses absorb enormous quantities of carbon dioxide, helping to mitigate the effects of climate change in a region already suffering from increasing drought. Also, with large predators at the top of the food chain, the complex maintains a balance in herbivore populations, preventing overgrazing and preserving plant diversity.

Despite its importance, the WAP National Park faces existential threats that require decisive international intervention. Recent years have seen a deterioration in the security situation in the Sahel region, with increased activity by armed groups. This has directly impacted the rangers’ ability to conduct patrols and, in some areas (particularly in Burkina Faso and Niger), has led to the cessation of tourism activities, depriving the park of significant revenue.

According to Feyi Ogunade:

“…the WAP’s million hectares of remote landscape is also a hub for organised transnational crimes, including the trafficking of weapons, drugs and people.

Weapons smuggling is the most prolific illegal activity in the WAP, says Dr Juliana Abena Appiah from the University of Ghana’s Legon Centre for International Affairs and Diplomacy. Carried out mainly by armed groups who exploit the park’s rugged terrain and porous borders, the flow of weapons and ammunition facilitates terrorism, poaching, banditry and communal violence.”

Elephants remain threatened for their ivory, and lions for their skins and body parts used in traditional medicine. Hunting for local consumption (bushmeat) also puts continuous pressure on antelope and other wildlife populations.

Population growth in the surrounding areas is putting pressure on the park’s periphery to convert it into farmland. The illegal entry of large herds of cattle into the park’s boundaries leads to competition for resources and the transmission of diseases between native and wild animals.

The survival of the W-Arly-Pendjari Complex depends on a “transboundary management” model. Cooperation between Benin, Burkina Faso, and Niger is key to ensuring that there are no safe havens for poachers and to facilitating the movement of animals.

Drones and satellite tracking collars are currently being used to monitor the movement of large herds and detect any suspicious poacher activity. Experience in Pendjari National Park has also shown that empowering local communities to become partners in conservation, through job creation and development projects, is the most effective way to reduce poaching.

Yet, the WAP requires continued international funding from institutions such as the World Bank and the Global Environment Facility to strengthen security infrastructure and protect archaeological and environmental sites within the area.