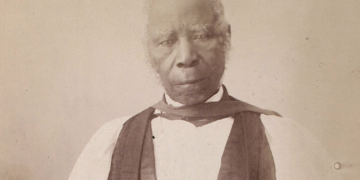

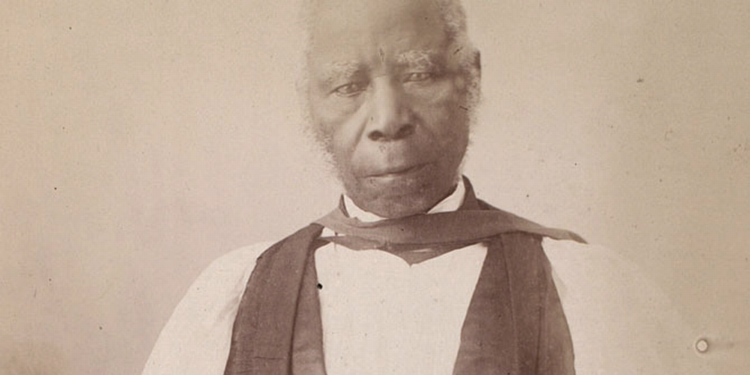

Samuel Ajayi Crowther, the first African Anglican bishop, is remembered for his role in linguistics, translation, Christianity in Southwest Nigeria, and cultural mediation between European systems and local communities in West Africa.

Ajayi was born in 1809 in the town of Osogun in the Yoruba region (present-day Nigeria). In 1821, during the civil wars that ravaged Yorubaland, Ajayi was captured by slave traders and sold several times before ending up on a Portuguese ship bound for Brazil.

A major turning point came when a British Royal Navy patrol intercepted the Portuguese ship as part of Britain’s efforts to abolish the transatlantic slave trade. Ajayi was taken to Freetown in Sierra Leone, a colony designated for the resettlement of freed slaves. There, he was educated by the Church Missionary Society (CMS) and converted (from the traditional beliefs of the Yoruba people) to Christianity in 1825, taking the name Samuel Crowther after a prominent British clergyman.

Ajayi demonstrated exceptional intellectual abilities in learning languages and the sciences. He was sent to England for a short period before returning to become the first student enrolled at Fourah Bay College in Sierra Leone in 1827.

Ajayi recognized that disseminating ideas required an intermediary language understood by the native population. He embarked on a major scholarly project to document the Yoruba language. In 1843, he published his book, “A Grammar of the Yoruba Language,” followed by a comprehensive dictionary.

Ajayi laid the linguistic foundations for writing Yoruba using the Latin alphabet, a work considered a cornerstone of modern Nigerian literature. Although, he also faced many criticisms, especially due to his mistranslation of many Yoruba words and vocabulary and his role in promoting Christianity and the expense of local cultures.

Ajayi participated in the Niger River Expeditions (1841, 1854, 1857) organized by the British government and the Church Missionary Society. These expeditions aimed to explore the potential for trade, agriculture, and missionary work in the interior of the continent.

Ajayi’s role in these missions was noted by his ability to connect with local leaders as what they considered an “educated African,” which facilitated negotiations and the establishment of trading and missionary stations. In the 1854 mission, he played a key role in demonstrating that the use of quinine could reduce European deaths from malaria, paving the way for deeper penetration into the continent.

Ajayi was consecrated Bishop of the Western Niger Territory on June 29, 1864, at Canterbury Cathedral in England. This appointment was considered a historic and unprecedented event, reflecting a trend within the Church of England (led by Henry Finn) advocating for the establishment of “local churches” run by Africans themselves.

As bishop, Ajayi oversaw the construction of schools and missionary stations along the Niger River, striving to reconcile Christian practices with local traditions, while consistently emphasizing technical and agricultural education as tools for social advancement.

His later years were not without their challenges. With the dawn of formal colonization of Nigeria in the late 19th century, European attitudes toward African leadership shifted. A new generation of white missionaries emerged, espousing racist or supremacist ideas and questioning Ajayi and his African team’s ability to manage the diocese’s finances and administration.

Ajayi came under immense pressure, and his authority was gradually undermined by commissions of inquiry sent by the Society from London. Despite his attempts to defend the integrity of the African cadre, these conflicts ultimately led to the resignation of many of his aides and the disintegration of part of his administrative network before his death.

According to Boston University’s School of Theology:

“In the 1880s clouds gathered over the Niger Mission. Crowther was old, Venn dead. The morality or efficiency of members of Crowther’s staff was increasingly questioned by British missionaries. Mission policy, racial attitudes, and evangelical spirituality had taken new directions, and new sources of European missionaries were now available. By degrees, Crowther’s mission was dismantled: by financial controls, by young Europeans taking over, by dismissing, suspending, or transferring the African staff. Crowther, desolated, died of a stroke. A European bishop succeeded him.

“Part of the Niger Mission retained its autonomy as the Niger Delta Pastorate Church under Crowther’s son, Archdeacon D.C. Crowther, and at least one of the European missionaries, H.H. Dobinson, repented of earlier hasty judgments..”

Ajayi Crowther died on December 31, 1891, in Lagos. Despite the political challenges he faced at the end of his life, his legacy endures in several areas. The translation of the Bible into Yoruba helped unify the dialects of this language. The schools he founded produced the first generation of what the West and the eurocentric writers considered “educated elites” in Nigeria. He also demonstrated that Africans could hold the highest positions in international institutions at a time when their incompetence was widely believed.

During a ‘thanksgiving and repentance’ service marking the 150th anniversary of Ajayi’s ordination, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, apologized for his ill-treatment by the Church of England, saying:

“This is a service of thanksgiving and repentance. Thanksgiving for the extraordinary life that we commemorate [and] repentance, shame and sorrow for Anglicans who are reminded of the sin of many of their ancestors.

“We in the Church of England need to say sorry that someone was properly and rightly consecrated bishop and then betrayed and let down and undermined. It was wrong.”