The Herero people are one of the most prominent ethnic groups in Southern Africa, with their main population concentrated in Namibia and smaller communities in Botswana and Angola. They belong to the Bantu language family, and their history is marked by a series of transformations, from a settled pastoral lifestyle to facing one of the most brutal colonial conflicts of the early 20th century, culminating in their resurgence as a social and political force in modern Namibia.

Historically, the Herero are believed to have migrated south from the Great Lakes region of East Africa, settling in Namibia by the 18th century. Unlike other groups that relied on agriculture, the Herero were considered “aristocratic pastoralists,” with cattle at the heart of their economic, spiritual, and social lives.

Cattle was a source of food and a measure of wealth and social status. The Herero divide their herds into ordinary cattle for consumption and trade and “sacred” cattle used in funeral rites and religious ceremonies. This close connection to the land and pastures has kept them in constant contact and conflict with expansionist forces, whether from neighboring tribes or European colonizers.

The Herero people possess a unique double kinship system, a rare anthropological phenomenon. Individuals in this society belong to both the paternal and maternal clans simultaneously. The paternal clan is responsible for religious affairs, rituals, and inheritance related to sacred cattle. The maternal clan is responsible for general economic affairs and non-ritualistic material inheritances.

This structural balance has contributed to the cohesion of the society and its ability to reorganize itself even in the most dire political circumstances. The year 1904 marked a tragic turning point in Herero history. With increasing pressure from German colonists to seize land and grazing areas, a major rebellion erupted, led by Chief Samuel Maharero.

The German forces, under the command of General Lothar von Trotha, responded by issuing the “Extermination Order,” which mandated the killing of any Herero found within the colonial borders. Thousands of people were driven into the arid Omahekê Desert, where they were denied access to water. This resulted in the deaths of approximately 75% to 80% of the Herero population from thirst, starvation, and direct killing.

These events are now classified by many historians and international organizations as the first genocide of the 20th century. This era left a deep wound in the Herero collective consciousness, and the issue of reparations and a formal apology from Germany remains a complex diplomatic matter between Berlin and Windhoek.

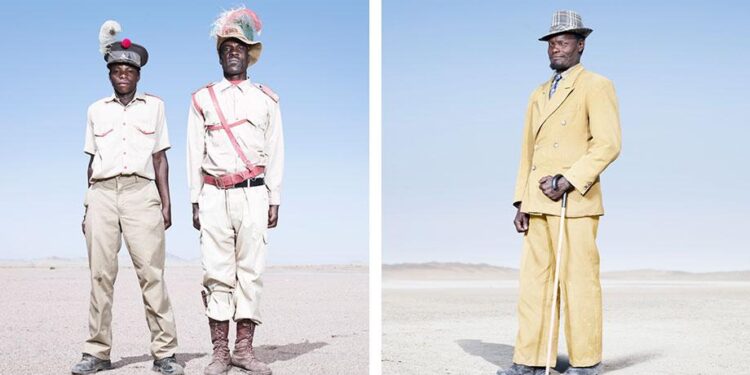

Ironically, the Herero absorbed some elements of European culture and transformed them into symbols of resistance and identity. This is clearly evident in the traditional dress of Herero women.

Herero women wear long, flowing dresses inspired by the attire of German missionary wives in the Victorian era, but they added a unique headdress resembling cattle horns. This attire is not merely an imitation of the colonizer but rather a form of “reverse cultural appropriation” intended to demonstrate dignity and resilience in the face of cultural subjugation. Men, in particular, often wear historically themed military uniforms during national celebrations to honor ancestors who fell in war.

The Herero speak Otjiherero, a living language taught in Namibian schools and used in the media. Today, they are distributed across several regions. In Namibia, they are concentrated in the areas of Omakeke, Otjozondjupa, and the capital, Windhoek. In Botswana, as descendants of refugees who fled the German genocide in 1904, they have maintained their language and identity despite integration into Botswana. While in Angola, subgroups such as the Himba exist, who share a linguistic origin with the Herero but have maintained a more traditional and isolated pastoral lifestyle.

Besides, it is impossible to discuss the Herero without mentioning the Himba of northern Namibia. While the Herero were influenced by urbanization, Christianity, and Western dress, the Himba remained firmly rooted in their pastoral traditions, covering their bodies with a mixture of red ochre and fat to protect their skin and living in fortified, circular villages. The Himba represent the “living memory” of the Herero people’s original way of life before colonial contact.

The Herero play an active role in Namibian politics, participating in opposition parties and holding government positions. Economically, they remain among the country’s largest cattle owners and contribute significantly to the meat production sector, a cornerstone of the national economy.

However, the issue of land ownership remains the greatest challenge. Due to the unequal distribution of land inherited from the colonial and apartheid eras, vast tracts of fertile pastureland remain owned by minorities of European descent, creating social pressure from Herero youth demanding comprehensive land reform.

Maharero Day is the most important annual event for the Herero people in Okahandja. Thousands from across the region gather, dressed in their military and traditional attire, to visit the graves of their leaders. This celebration is also a political and cultural demonstration intended to affirm the unity of the people and invoke their shared history as a tool to confront the challenges of the present.

Herero communities face several pressing issues in the 21st century. The migration of young people to cities in search of work threatens the continuity of their traditional pastoral way of life and their mother tongue. Also, Namibia suffers from frequent and severe droughts, threatening the livestock that is the lifeblood of the Herero people. Continued pressure for full recognition and direct reparations from Germany for past atrocities, a process characterized by slowness and legal complexities.