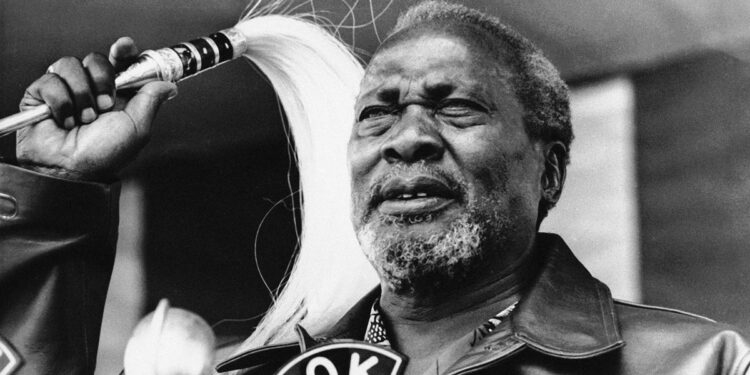

Jomo Kenyatta is an important figure in modern Kenyan history as the man whose name is synonymous with the transition from British colonial rule to sovereign independence. In his homeland, he is affectionately known as “Mzee,” a Swahili word meaning “wise elder” or “father,” reflecting his status as the founder of the Kenyan nation and its first president.

Jomo Kenyatta was born in the 1890s (likely 1893 or 1894) in a small village in central Kenya, to a Kikuyu family, the country’s largest ethnic group. His birth name was Kamau wa Ngengi. He enrolled in a Scottish missionary school, where he received his early education and was baptized in the church as Johnstone Kamau.

In his youth, he moved to Nairobi, where he worked for the city’s water department. During this time, his political awareness began to develop as a result of racial discrimination and the British appropriation of African tribal lands for the benefit of white settlers. He later changed his name to Jomo Kenyatta, the first name derived from a word meaning “flaming spear” and the second from a traditional belt he wore.

In 1929, Kenyatta traveled to London to represent the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA), a political organization that sought to reclaim stolen lands and improve the lives of Africans. This trip marked the beginning of a nearly 15-year period of exile that shaped his political and global outlook.

While in Europe, Kenyatta studied at the London School of Economics (LSE) under the renowned anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski. This study culminated in his seminal work, “Facing Mount Kenya,” published in 1938, in which he presented a scholarly and compelling defense of Kikuyu culture and social order, challenging the colonial view that African societies were “primitive.”

In 1945, Kenyatta helped organize the Fifth Pan-African Conference in Manchester, alongside historical figures such as Kwame Nkrumah and W.E.B. Du Bois. This conference served as a resounding call for the end of colonialism in Africa, with attendees demanding complete independence and the right of peoples to self-determination.

Kenyatta returned to his homeland in 1946 to find a country seething with discontent. He assumed the presidency of the Kenya African Union (KAU) and began traveling the country, calling for political reforms. As the colonial authorities became increasingly intransigent, the Mau Mau armed insurgency erupted in the 1950s. This clandestine movement launched attacks against white settlers and their collaborators.

Although Kenyatta publicly advocated for constitutional and peaceful change, the British administration accused him of organizing and leading the Mau Mau. In 1952, he was arrested as part of a group known as the Kapenguria Six. He was sentenced to seven years of hard labor, followed by exile to a remote area in northern Kenya. During his years in prison, Kenyatta became a symbol of resistance, and the demand for his release became a unifying national cry.

Under increasing international and domestic pressure, Kenyatta was released in 1961. He led his party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), in the Lancaster House negotiations in London to draft the new constitution. On December 12, 1963, Kenya gained its independence, and Kenyatta became its first prime minister, then president the following year.

From the moment he took office, Kenyatta embraced a message of reconciliation. In a famous symbolic gesture, he invited white settlers to stay and contribute to building the new nation, emphasizing the need to “forget the past” and work for the future. His national motto was “Harambee,” a Swahili word meaning “let’s all work together,” which became an official philosophy for building schools and hospitals through community-based efforts.

Kenyatta opted for a moderately capitalist economic model. He encouraged foreign investment and maintained strong ties with the West, resulting in high rates of economic growth during the first decade of his rule, a period known as “Kenya Stability.”

However, his domestic policies faced significant criticism. Over time, Kenya effectively became a one-party state, and Kenyatta severely restricted political opposition. He was accused of favoring members of his Kikuyu tribe in government positions and land distribution, sowing the seeds of the ethnic tensions that Kenya later experienced. And, while land reform was successful in some respects, vast tracts of land ended up in the hands of a political elite close to the political palace, creating stark class disparities.

His rule was marked by dramatic events that shook his image. The assassination of the charismatic politician Tom Mboya in 1969 was a dark turning point; Mboya was seen as a potential successor and a representative of the modern, cross-tribal voice. This assassination sparked widespread protests and deepened the divide between the Kikuyu and Luo tribes.

His later years were characterized by health and political isolation, with a group of close associates known as the “Kiambu clique” controlling key decision-making positions, raising concerns about the transfer of power after his death.

On the international stage, Kenyatta was a prominent figure in the Organization of African Unity, but he also maintained close ties with Britain and the United States during the Cold War, which provided Kenya with military and economic stability, despite criticism from leaders on the continent who considered him an appeaser of neocolonialism.

Jomo Kenyatta died on August 22, 1978, in Mombasa, leaving behind a country that was relatively stable politically and economically compared to its neighbors but burdened with structural challenges.

Kenyatta’s legacy can be summarized in two overlapping aspects. His success in preventing state collapse after independence, building a national identity under the Harambe banner, and achieving significant economic prosperity in the 1970s. However, the establishment of a strong presidential system lacking democratic institutions and the legitimization of ethnic favoritism in the distribution of state resources—problems that Kenya struggled to address for decades afterward.