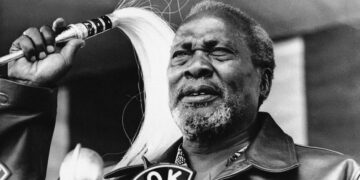

Dr. Bennet Omalu is a Nigerian-American forensic pathologist and neurologist. He is known for his keen observation and scientific dedication, uncovering a devastating disease that was silently ravaging the minds of elite athletes, putting him in direct conflict with the National Football League (NFL).

Bennet Omalu was born in September 1968 in Enugwu-Ukwu, a town in southeastern Nigeria, the sixth of seven children. He was born amidst the Nigerian Civil War (the Biafran War), which forced his family to live as refugees for a time. This harsh beginning left a profound mark on his character. His father was a local leader and civil engineer who instilled in his sons the value of education.

Omalu displayed early academic brilliance, enrolling in medical school at the University of Nigeria (Nsukka) at the age of sixteen and graduating with a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) in 1990. After a brief period working in Nigeria, he sought broader scientific horizons and emigrated to the United States in 1994. There, he embarked on a distinguished academic and professional career, completing specializations in pathology and forensic pathology at prestigious universities such as the University of Washington, Columbia University, and the University of Pittsburgh.

In 2002, while Omalu was working as a medical examiner at the Allegheny County Medical Examiner’s Office in Pittsburgh, the body of Mike Webster arrived at his morgue. Webster was a legend of American football and a former player for the Pittsburgh Steelers, but he had died at the age of 50 after years of struggling with dementia, depression, and severe mental health issues that had left him living a disoriented life in his car.

The prevailing explanation at the time was that Webster was suffering from “boxer’s dementia” or simply the effects of premature aging. But Omalu, who knew little about American football, wasn’t convinced. How could an athlete at the peak of his physical abilities lose his mind so rapidly?

Funding himself, Omalu decided to examine Webster’s brain extensively under a microscope, expecting to find signs resembling Alzheimer’s disease. But he found something entirely different; he found dense accumulations of a protein called tau protein in specific brain regions, accumulations that choked nerve cells and disrupted cognitive functions. Omalu realized he was dealing with a new and unique medical condition resulting from repeated head trauma, which he later named Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

In 2005, Omalu published his findings in the scientific journal Neurosurgery in an article titled “Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a National Football League player.” He expected the NFL to welcome this discovery as an opportunity to protect its players, but the reaction was quite the opposite.

The NFL formed a special medical committee (the Mild Brain Injury Committee) that fiercely attacked Omalu’s research, demanding the journal retract the article and describing his conclusions as “completely wrong” and “misleading.” Omalu faced immense professional and psychological pressure. He was accused of trying to destroy “America’s favorite sport,” and some questioned his competence as a foreign doctor who “didn’t understand American sports culture.”

Despite the attacks, Omalu didn’t back down. Instead, he continued his research, examining the brains of other players who had committed suicide or died under mysterious circumstances, such as Terry Long and Andre Waters. In each case, he found the same destructive pattern of tau protein, which strengthened his scientific hypothesis and made it difficult for the medical community to ignore the truth.

It took years of controversy, pressure from the families of affected players, and investigative journalism before the NFL indirectly acknowledged in 2009 a link between repeated concussions in American football and long-term brain damage.

Omalu’s discovery led to radical changes in the world of sports. Strict rules were implemented preventing players from returning to the field immediately after a blow to the head, and companies began designing more impact-absorbing helmets. Also, parents became more cautious about enrolling their children in contact sports, while concussion was no longer confined to American football; research began in boxing, wrestling, soccer (resulting from heading the ball), and even among veterans who had been injured in explosions.

In 2015, Omalu’s story reached a wider audience through the international film “Concussion,” starring Will Smith as Dr. Omalu. The film highlighted the ethical and scientific struggle Omalu faced and how he sacrificed his professional stability to reveal the truth. It helped transform the CTE issue from a private medical debate into a global public concern.

Bennett Omalu believed that medicine is a “sacred calling” and that the forensic pathologist is the “advocate of the dead,” speaking the truth they could not articulate while alive. His approach is characterized by meticulous attention to detail and empathy for the bodies he examines.

In his books, such as “Truth Doesn’t Have a Side,” Omalu discusses the difficulties he faced as an African immigrant trying to speak the truth in a society that idolizes money and sports. He has always emphasized that his goal was never to ban soccer, but rather to give players and parents the “informed consent” to understand the risks they might face.

He served as the chief medical examiner for San Joaquin County, California, for many years and is currently a professor in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis). He has received numerous prestigious awards, including the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Award of Excellence, in recognition of his contributions to public health.