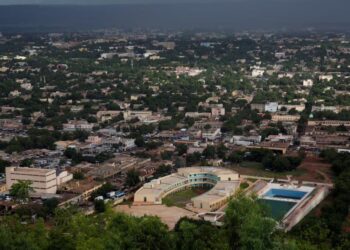

The Royal Palace of Porto-Novo, known locally as “Honmé” (meaning “inside the door”), is an important historical and cultural landmark in the Republic of Benin. Located in the heart of the administrative capital, Porto-Novo, it stands as a testament to the history of the Hogbonou Kingdom (also known as Adjatchè/Ajase or Porto-Novo), one of the most powerful kingdoms in West Africa before the colonial era.

The Kingdom of Porto-Novo was founded in the 16th century by princes of the Adja ethnic group who migrated from the Allada region. Initially known as Adjatchè, the kingdom was later renamed Porto-Novo (New Port) by the Portuguese due to its strategic location on the lagoon, which facilitated trade.

The Royal Palace was built to be the official residence of the “Toffa,” the title given to the kings of this kingdom. Over the centuries, the palace has undergone successive expansions and renovations, each reflecting a specific era, from the flourishing palm trade to the signing of protection treaties with the French in the nineteenth century, which distinguished Porto Novo from the neighboring Kingdom of Dahomey, which chose the path of direct military confrontation.

The Royal Palace is distinguished by its design, which blends two distinct architectural styles, making it unique.

- Traditional African Style: This style is evident in the older parts of the palace, where red clay (laterite) was used to construct thick walls that provided natural thermal insulation. The roofs were originally made of thatch before being replaced by metal sheets. The rooms are arranged around open courtyards (patios), an architectural design intended to foster social interaction and provide continuous ventilation in the humid tropical climate.

- Atlantic and Portuguese Influences: As a result of long-standing trade with Portugal and Brazil, the palace incorporates Afro-Brazilian architectural elements, such as tall wooden windows, wrought-iron balconies, and stucco decorations surrounding doorways. This fusion reflects the ingenuity of the Porto-Novo monarchs in absorbing and adapting incoming cultures to serve the prestige of the royal throne.

The palace was the king’s residence and a “city within a city.” The complex spanned a vast area, encompassing sections dedicated to specific functions:

- The King’s Pavilion: This was the most private and oldest part of the palace, where the king conducted state affairs and received advisors.

- The Queens’ Pavilions: The king had several wives, each with her own staff and a designated area within the palace. This necessitated meticulous administrative organization to prevent conflicts and ensure the palace’s needs were met.

- Ritual Courtyards: The palace included large courtyards dedicated to religious and national celebrations. These were the venues for the Masquerade dance and ceremonies associated with local Voodoo beliefs, which intertwined with royal practices.

In 1988, large sections of the palace were transformed into an official museum known as the Honmè Museum with the aim to protect and promote the kingdom’s tangible heritage for future generations and tourists. Museum Collections

The museum houses a rich collection of artifacts that tell the story of the kingdom, most notably:

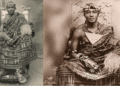

Royal Thrones: Intricately carved wooden thrones, each bearing symbols representing the reign of a particular king (such as the lion, the elephant, or the ship).

- Ornaments and Clothing: The splendor of the royal court is evident in the hand-embroidered fabrics and bronze and gold jewelry.

- Photographs and Documents: The museum contains a photographic archive of the kings, particularly King Tufa IX, who lived during the French occupation, as well as old maps illustrating trade routes across the lake.

- Musical Instruments: Large drums and aguju (bells) that were used to announce royal decrees or in funeral rites.

The Royal Palace in Porto-Novo played a crucial diplomatic role in Benin’s history. The kings of Porto-Novo pursued a policy of “diplomatic pragmatism.” The palace was the site of vital agreements that later made Porto-Novo the center of French administration, which is why it remains the country’s official capital to this day, despite the economic importance of Cotonou.

This policy made the palace a meeting place of cultures. Within its halls, discussions took place between traditional leaders, Brazilian traders returning from slavery, and colonial officials, creating a unique cultural identity characterized by tolerance and openness.

Built from natural materials (clay and wood), the Royal Palace faces ongoing challenges related to restoration. The high humidity in the Lake District causes erosion of the walls, necessitating costly and periodic maintenance. The Ministry of Culture in Benin, in cooperation with international organizations, is working to preserve the palace within UNESCO standards, as the palace is part of the nominated World Heritage due to its exceptional historical and architectural value.