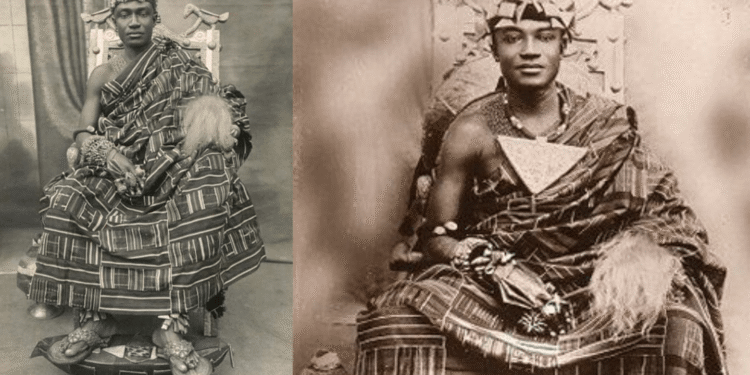

Osei Tutu is considered the most influential historical figure in shaping the political and social identity of the Ashanti people in present-day Ghana. He was a leader and the architect of a sophisticated federal system that endured for centuries, uniting a collection of scattered chiefdoms under a single banner.

Osei Tutu was born around the mid-17th century, at a time when the rainforest region of present-day Ghana was divided among small states under the powerful Denkyira Empire. These states, including Kwaman (later known as Kumasi), paid taxes and tribute to the Denkyira king.

According to the Dictionary of African Biography (Oxford Reference):

“His mother, Manu Kotosii, was the sister of Oti Akenten, ruler of Kwaman, and Obiri Yeboa, future ruler of Kwaman. Not much is known about his father, who was called Owusu Panin. In any case, the mother of a child is of more importance among the Asante because of the matrilineal system of inheritance.”

Osei Tutu spent part of his youth at the court of the Denkyira king, either as a political hostage or to learn the arts of administration, before moving to the Akwamu region, where he met the spiritual and political advisor Okomfo Anokye. This meeting between the political mind of Osei Tutu and the strategic vision of Anokye was the cornerstone for the emergence of the new nation.

When Osei Tutu assumed leadership of the Kwaman state around 1680, he embarked on a plan to unify the Akan-speaking tribes to counter the dominance of the Dinka. His unification relied not only on military force but also on ideological and organizational foundations:

According to a source:

“Skillfully utilising a combination of spiritual dogma and political skill, supported by military prowess, Osei Tutu tripled the size of the small kingdom of Kumasi, which he inherited from his uncle Obiri Yeoba and laid the foundation for the Empire of Ashanti in the process.”

To give the union legitimacy that transcended narrow tribal interests, Osei Tutu enlisted the help of his friend Okomfo Anokye. According to Ashanti legend, Anokye is said to have brought down the Golden Stool (Sika Dwa Kofi) from the sky, which landed on Osei Tutu’s knees.

The Golden Stool became a symbol of the “spirit of the nation” and of the king’s authority. With it, Osei Tutu persuaded other tribal leaders to relinquish their independence to the union while simultaneously acknowledging him as the first Asantehene (King of the Ashanti).

Osei Tutu developed an administrative system known as the “Union System” (or Ashanti Confederacy), in which local chieftains retained some authority in their regions but pledged allegiance to the central king in Kumasi. Militarily, he borrowed organizational techniques from the Akwamu State, dividing the army into wings (right, left, center, and vanguard), which gave the Ashanti a tactical advantage in their subsequent battles.

The most significant event in Tutu’s reign was the Battle of Feyiase in 1701. In this battle, the Ashanti forces clashed with the Denkyira army. The battle ended in a decisive Ashanti victory and the death of the Denkyira king, Ntim Gyakari.

It was believed that “the Akyem brought the Asante to the attention of the Europeans on the coast for the first time, as the victory broke the Denkyira hold on the trade path to the coast and cleared the way for the Asante to increase trade with the Europeans.”

This victory liberated the Ashanti from subjugation and established them as the dominant power in the region. The empire expanded to encompass vast territories and controlled vital trade routes connecting the African interior to the coast, where Europeans (the Dutch and the English) had established their trading posts.

Tutu did not limit himself to military expansion; he also enacted laws aimed at forging a unified Ashanti identity. He prohibited citizens from discussing ancient tribal origins or the history of conflicts among the founding members of the confederation. The goal was to erase old grudges and build a unified Ashanti identity.

The customary constitution also laid the foundations for how the king was chosen, emphasizing the matrilineal system of inheritance, a complex social system that ensured the stability of the transfer of power within the ruling dynasty.

Under Osei Tutu, Kumasi became an international trading center. The empire exported gold and enslaved persons in exchange for firearms, textiles, and European goods. The king controlled the gold mines, providing substantial financial resources to fund the army and central administration.

While the enslaved persons trade was a part of the economic reality of the time, the Ashanti under Osei Tutu also focused on building a robust internal road network to facilitate the movement of trade caravans and the rapid mobilization of military forces.

Osei Tutu died under mysterious circumstances around 1717. It is believed he was killed during a military campaign against the Akyem tribes while crossing the Pra River. His sudden death was a shock, but the political structure he had built was strong enough to sustain the empire.

The state established by Osei Tutu paved the way for fierce resistance against British occupation in the 19th century (the Ashanti Wars). The position of “Ashantihene” still exists today in modern Ghana as a widely respected cultural and spiritual symbol, and the golden throne is still considered the people’s most sacred object.