The Dogon are a branch of the Niger-Congo language group, a tribe of anything between 400,000 and 800,000. They live in villages in good defensive locations on the Central Plateau of Mali and into Burkina Faso. They are mainly an agricultural people; their few craftsmen, largely metalworkers and leatherworkers, form distinct castes.

A hogon, or spiritual leader, is in charge of each sizable district, and there is a supreme hogon over the entire nation. The Dogon attribute a much of their social structure and culture to the tale of creation, which the hogon represents in his attire and demeanor. Unlike most other African peoples, they have a more abstract metaphysical system that personifies good and evil, classifies physical objects, and outlines the spiritual tenets of the Dogon mentality.

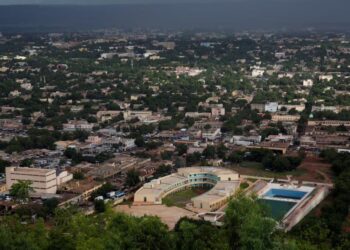

They have no centralized system of government but live in villages composed of patrilineages and extended families whose head is the senior male descendant of the common ancestor. Polygyny is practiced but reportedly has a low incidence. There is some doubt as to the correct classification of the many dialects of the Dogon language; the language has been placed in the Mande, Gur, and other branches of the Niger-Congo language family, but its relationship to other languages of the family, if any, is uncertain. The majority of them live in the rocky hills, mountains, and plateaus of the Bandiagara Escarpment.

The Bandiagara Escarpment, a sandstone cliff of up to 500 metres (1,600 ft) high, stretching about 150 km (90 miles). To the southeast of the cliff, the sandy Séno-Gondo Plains are found, and northwest of the cliff are the Bandiagara Highlands. Historically, Dogon villages were established in the Bandiagara area a thousand years ago because the people collectively refused to convert to Islam and retreated from areas controlled by Muslims. Their lives revolve around their traditional religion though some are now Muslims and others, Christians.

Famous for their art and their astronomical knowledge. Engaging with the Dogon tribe goes beyond appreciating their cultural heritage. It also involves understanding their struggles and the importance of preserving their traditions in a rapidly changing world. The Dogon face various challenges, including cultural assimilation pressures, climate change impacting agriculture, and limited access to education and healthcare.