In independent Zimbabwe, the country’s ruling group emerged from the crucible of an anticolonial liberation war. Its political strategies and tactics cannot be understood apart from this heritage. Political leaders opted for violence, first as a reaction against the brutalities of settler colonialism, later as a means of retaining their tight grip on the bountiful privileges of state power. In imposing their preferred political settlement on the Zimbabwean population, ZANU-PF created a militarized version of an electoral authoritarian regime. Winning its political independence from white minority rule in 1980, Zimbabwe emerged as a promising nation. The new prime minister, Robert Gabriel Mugabe, preached hope and reconciliation. There was euphoria at independence as the nation celebrated political freedom achieved through war and highly emotive negotiations at the Lancaster House Conference. Before the first half of the decade passed, the new government was already engaged in a war against its citizens, dubbed Gukurahundi.

Withal, the post-independence Zimbabwean government has adopted and implemented policies and projects shaped by different ideological frameworks at different epochs, which have been defined as contradictory in nature. These policy shifts have followed a trend towards socialism (e.g., free education, free access to medical care) in the early years of independence and moved to an extreme position towards capitalism with the implementation of the economic recovery programs, thus reversing the gains of the quasi-socialist era. Governments uphold certain views shaped locally and internationally at different historical epochs. As the state imposed a series of seemingly well-intentioned and sometimes even widely welcomed food initiatives such as Operation Maguta and BACOSSI, these food security measures were often ad hoc, temporary, and—as intellectuals argue—actually had an adverse long-term impact on local grain production and food availability. The government worked through key parastatals like the Grain Marketing Board and the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe to allocate resources and food support to ruling party loyalists. During this period, the ZANU-PF regime was concerned primarily with holding on to its waning political power and avenues for personal wealth accumulation at the expense of food security in the country.

Today, Zimbabwe is undergoing seismic political and economic shifts that leave no facet of society untouched. While changes may neither be visible nor palpable, their effects on civil society are both comprehensive and unmistakable. This explains the pivotal movements taking place in some social sectors, principally within the ruling ZANU-PF party. Meanwhile, this article provides a detailed analysis of the political instability in Zimbabwe, which in turn has a negative impact on the economic climate of the country, by looking back into the history of the nation from the era of the former leader Robert Mugabe to the current regime of Emmerson Mnangagwa.

Mugabe’s Legacy and Mnangagwa’s Challenge

Besides, the post-colonial Zimbabwean state that emerged after 1980 was superimposed on a neocolonial economic structure characterized by heavy dependence on South Africa following 15 years of sanctions against the Rhodesia state. This colonial structure had served the white settler community at the expense of the black masses. While white settler-colonialists had lost political power, they were still economically in control, a situation that exists to this day. Thus, the political independence represented in 1980 by the lowering of the Union Jack and the raising of the new Zimbabwe flag amounted to symbolism for the masses, which disguised an institutionalization of attempts towards a new alliance among the ruling black elite. Nevertheless, between 1998 and 2008, Zimbabwean politics witnessed a range of political and economic convulsions in which new social relations emerged, the state was reconfigured in more authoritarian nationalist terms, and the production of sovereignty through the nation and the state produced a series of citizen exclusions from what was constructed as the ‘authentic nation’ by the ruling party. These exclusions were carried out through a combination of the law, the abuse of state institutions, and state-led and -supported violence. A key element of this state restructuring was a revived nationalist discourse located around a number of themes, namely the centrality of the land, a selective rendition of the history of liberation, and the collective branding of whites, the West, the Movement for Democratic Change, and the civic movement and their supporters as ‘enemies of the state’ and outsiders to the nation.

The Mugabe Program of Africanization

Although African “big men” set the tone for a regime of governance, they almost never govern entirely alone. After all, politics is the art of the possible: leaders govern using the endowment of material resources, inherited institutions, and political alliances available to them at any given time. These legacies create as many constraints as opportunities. To survive in office, a leader must, at minimum, serve the vested interests of his immediate coalition of supporters, an elite group that often shares a comradeship born from a common political struggle. Together, these allies seek to maximize the group’s collective advantage, usually to the exclusion of political rivals and ordinary citizens. Zimbabwe’s policies have, sometimes, been dismissed as senseless and motivated by little more than one man’s racism and megalomania, on one hand, or hailed as a truly patriotic and Africanist stance that is blazing a new trail in what one Mugabe admirer referred to as a new African Democratic Socialism, on the other.

Robert Mugabe and other liberation icons in Zimbabwe, like Herbert Chitepo, Leopold Takawira, Josiah Tungamiriai, and Ndabaningi Sithole, among others, led the war of liberation on the basis of reclaiming the land that was lost to imperial powers and the quest for self-rule. Long before he joined mainstream politics, and soon after graduating from Chalimbana Teacher Training College in Zambia in 1957, Mugabe echoed the struggles and poverty among the black people in Zimbabwe. He bemoaned the land hunger that was rampant among the Black natives who, during those days, were forced into what the whites called the ‘Reserve or the Tribal Trust Lands. Individual white farmers were given by Rhodes vast tracts of land, some measuring as much as 3000 ha, while the thousands of local people were crammed into less than 1000 hectares. In his autobiography, Mugabe makes reference to the inspiration he got from the Catholic Bishop of Mutale Diocese, called Bishop Lamont, a critic of the Rhodesian government and advocate of land reclamation. Bishop Lamont was later deported back to Germany in 1977 by the Smith Regime for supporting the liberation cause, especially the land question. What this suggests is that the land question was going to remain a political issue even if Mugabe had not used it for his election.

One of the undoubted achievements of Mugabe’s twenty-seven years in power was the expansion of education. At 90 percent of the population, Zimbabwe has the highest literacy rate in Africa. However, in 1990, a struggling economy forced Zimbabwe to adopt a World Bank Structural Adjustment Program, which called for the Mugabe government to move away from Marxism in favor of a freer economy. In 2000, a controversial land resettlement process began whereby 10 million hectares of white-owned farmland were effectively seized by the state and turned over to settlers who ranged from peasant farmers to members of the political elite. In 2008, Zimbabwe held very controversial parliamentary and presidential elections, which saw the MDC winning a majority in parliament and MDC president Morgan Tsvangirai winning the presidential race marginally, thus necessitating a run-off. The violence that was unleashed by ZANU-PF at this point was such that Tsvangirai withdrew from the race, leaving Mugabe to claim victory. The political stalemate that followed was only resolved when the Southern African Development Community (SADC) brokered a power-sharing agreement between ZANU-PF and the two MDC parties, which was meant to provide an opportunity for the parties to negotiate and implement certain reforms that would enable the country to hold peaceful and fair elections in the future.

Zimbabwe’s Political Landscape: The Mnangagwa Factor

Zimbabwe has for decades been mired in political crises that have led to economic stagnation, a dearth of jobs, and general government dysfunction. Hyperinflation over the past two decades has pushed the South African country’s economy to its knees and wiped out the savings of common people. Emmerson Mnangagwa is currently serving his second and presumably final term as head of the ZANU-PF party, which has ruled Zimbabwe since the country’s independence from Britain in 1980. Mnangagwa became president in 2017, following a coup that overthrew longtime leader Robert Mugabe. In January, ZANU-PF party leaders passed a resolution that Mnangagwa should seek a third term via a constitutional amendment. He has assured the public that he will retire when his term ends in 2028, yet many remain skeptical. The prospect of Mnangagwa extending his stay in office has elicited public outrage and resulted in calls for mass protests at the end of March by veterans of the nation’s war against White-minority rule. While the demonstrations didn’t materialize – in part because the police were deployed in large numbers in the capital, Harare, and other cities to quell any unrest — many citizens voiced their disapproval of the government by staying away from work. Beyond political machinations, their anger has also been fermented by years of economic mismanagement and sky-high inflation.

The survival of ZANU-PF is also associated with the lack of determined opposition leadership. This absence of a robust opposition was itself shaped by the violence of 1977-79 experienced in the Zimbabwean rural districts of Mashonaland and Manicaland and subsequently in 1983-1987 in Matabeleland. A genuine democratic and social challenge to ZANU-PF only emerged in the late 1990s as the product of wider civil and social discontent. By the mid-late-1990s, the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) was able to overcome long-standing structural problems, including slow rates of union recruitment, non-payment of dues, and poor communications between central and regional organizations, through the formation of a wider civic alliance pressing for political reform and constitutional change: the National Constitutional Assembly. This intensification of pressure on the state led to the formation of the Movement for Democratic Change in 1999. From 2009 to 2013, Zimbabwe was governed by an inclusive government constituted by ZANU-PF and the two Movement for Democratic Change formations. The formation of the inclusive government involved a lot of political gamesmanship and negotiations, and it is of interest to examine how these affected the position of women in the country’s political processes. In 2013, ZANU-PF regained its parliamentary majority and, by extension, its sole mandate to govern the country. However, the triumph over opposition political parties, coupled with a looming elective congress, led to a lot of infighting in ZANU-PF, which affected women as well.

Military Manoeuvres and ZANU-PF

After a liberation war lasting 15 years (1964 to 1979), in 1980 Zimbabwe became independent under majority rule. One of the fundamental features of the political transition was to merge the former Rhodesian army and the two guerrilla armies, the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA), the armed wing of ZANU-PF, and the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA), an armed wing of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), into the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA). The new Zimbabwe army inherited the British military structure in terms of ranks, uniforms, training, administration, and housing. The idea was that the armed wings needed to be depoliticized and become ‘professional.’

In a piece by The Africa Report, political analyst Tendai Ruben Mbofana decries that the ZANU-PF party has never had peaceful transitions and says Zimbabwe has better leaders than Mnangagwa. “The problem with ZANU-PF is that they do not choose leaders on merit. It has more to do with who has the most power and can outmaneuver rivals.” Mbofana says the military establishment has always played a major role, citing Mugabe, who assumed power by ousting Ndabaningi Sithole through the 1975 Mgagao Declaration, which was authored by ZANLA forces in Tanzania. Mnangagwa was a longtime ally of Mugabe and served as defense minister and then vice president in the final years of Mugabe’s rule. He had close ties to the military. However, the two men fell out over who would succeed Mugabe: Mnangagwa was backed by the army on the one hand, while Mugabe wanted to hand over to his wife, Grace Mugabe, on the other.

Mbofana also noted that, “Mugabe was then toppled by Mnangagwa via a military coup in 2017 after [Mnangagwa] was fired as ZANU-PF and Zimbabwe’s vice president a week before the coup. The constitutionally mandated person to assume power until the next national elections in 2018 was the only remaining former vice president, Phelekezela Mphoko. Mnangagwa’s ascendancy was unconstitutional,” he adds. “[Mnangagwa] appears to have learnt nothing from the Mugabe era. He was one of the faction leaders plotting the coup against Mugabe. For some strange reason, Mnangagwa appears not to see that this is history repeating itself, as his refusal to step down will only further divide ZANU-PF and create instability in government.”

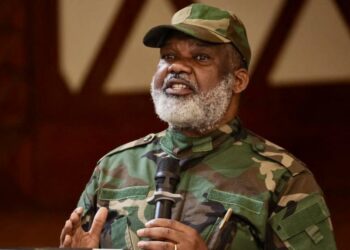

Blessed Runesu Geza (Bombshell) and his faction of war veterans have openly declared their intent to remove Mnangagwa from office. They plan to achieve this through mass action. However, Geza’s critics point out that he, too, is part of the establishment that has long controlled Zimbabwe. Analyst Takura Zhangazha told Al Jazeera that Geza’s opposition is gaining broader traction only because it comes at a time when the country’s national economy is also struggling—which Zimbabweans blame on the ruling government. Any support that Geza’s calls for Mnangagwa to resign get is not because people believe he will fight for them, he added. “Mr. Geza is representative of [the government] in the public eye,” Zhangazha said. “So he does not have an organic or popular authenticity.”

Brighton Chipamhadze, a Harare-based independent political commentator, told Voice of America (VOA) that Geza’s announcement shows the divisions within the ruling party. Moreover, political analyst Alexander Rusero says it is important to understand the war veterans’ influential role in both Zimbabwe and Zanu-PF. “They see themselves as caretakers, so you can’t wish away their sentiments,” he tells the BBC. However, he believes that the current grievances aired by the likes of Bombshell are prompted more by self-regard than public interest. “They feel as if they are excluded from the cake that they should otherwise be enjoying,” he tells the BBC.

Analysts say Mnangagwa appears to be acting to shield himself from a potential mutiny. A section of cadres of the ruling Zanu-PF party wants Constantino Chiwenga, Mnangagwa’s deputy, who removed Robert Mugabe in 2017 to take over as president. As scholars close to the ruling party have argued, Mnangagwa is not Mugabe in many respects, not least in his lack of political calculation and charisma. How such a man will be able to maintain his rule at the top of the party remains to be seen. Part of the answer seems to be an increasing reliance on his ethnic Karanga ties—a political dynamic that is new to Zimbabwe. This highlights another ZANU (PF) sacred cow that appears to have been slaughtered: the rule that the party leads the gun. The opposition will also need to think critically about its past and the conflicting legacies that have shaped it in both positive and negative terms, remembering that there are no guarantees for good conduct in the future.