Patrice Emery Lumumba is an exceptional figure who embodied the hopes of an entire people for freedom, dignity, and true independence. Lumumba was a resounding voice for justice and a symbol of African sacrifice and liberation, resisting colonial powers that did not hesitate to commit crimes to protect their interests.

Patrice Lumumba was born on July 2, 1925, in the village of Onalua in Kasai province, Belgian Congo. He grew up in a modest environment, receiving his education in missionary schools, and demonstrated an early intellect and a passion for knowledge. He worked in various jobs, including as a post office clerk and journalist, which gave him the opportunity to experience the harsh reality experienced by Congolese under Belgian colonial rule.

Lumumba witnessed the racial discrimination, economic exploitation, and political oppression practiced by the Belgian authorities against his people. These practices represented a denial of basic rights, a violation of human dignity, and the plunder of the country’s wealth for the benefit of the colonizer. These bitter experiences awakened in him a deep sense of injustice and a desire for change.

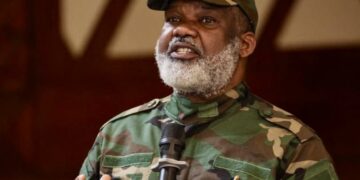

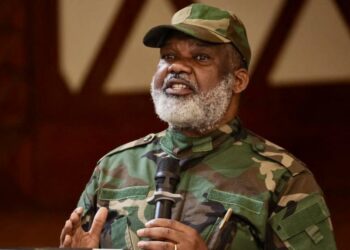

In the late 1950s, Lumumba began to become involved in the emerging Congolese nationalist movement. He possessed a charismatic personality and a remarkable ability to speak and influence the masses. He quickly emerged as a brilliant leader capable of uniting the various factions and tribes under the banner of independence. He founded the Congolese National Movement (MNC), which called for the independence of a unified Congo and rejected any form of partition or regional autonomy favored by some other Belgian-backed leaders.

On June 30, 1960, the dream Lumumba and his people had fought for was realized: Congo declared its independence, and Patrice Lumumba became the country’s first prime minister. On that day, Lumumba delivered a moving speech before Belgian King Baudouin, boldly exposing the brutality of Belgian colonialism and its decades-long exploitation of Congo. The speech heralded the beginning of a new era of dignity, freedom, and sovereignty for the Congolese people.

“We remember the ridicule, insults, and beatings we had to endure morning and night because we were ‘negroes.’ We recollect the atrocious suffering of those persecuted for political opinions or religious beliefs. Exiled in their own homeland, their fate was really worse than death itself,” he said, recalling that this independence was indeed the fruit of a “struggle.”

These honest and moving words shook the foundations of the official independence celebration and revealed the deep wounds that colonialism had left in the Congolespsyche. It was a roaring cry for freedom and justice that irked the colonial powers, who intended to preserve their economic and political clout in the newly independent Congo. The pleasure of freedom lasted only a short time, as Lumumba’s administration faced significant internal and external obstacles. The country’s infrastructure was shaky, the administration was unpredictable, and the army was disorganized. The previous colonial powers, led by Belgium, refused to surrender control of the Congo’s huge mineral resources, particularly in the copper-rich Katanga area.

With the complicity of major mining companies and some Western powers, who feared Lumumba’s irredentist and nationalist tendencies, conspiracies began to be hatched against Lumumba’s government. The secession of the wealthy Katanga region was supported under the leadership of Moïse Tshombe, a local leader close to Belgian interests. An armed conflict erupted, and the security situation in the country rapidly deteriorated.

Amid this chaos, Lumumba’s government sought assistance from the United Nations to protect the country’s unity and restore order. However, the UN, plagued by internal divisions and the influence of external forces, did not provide sufficient and effective support to Lumumba’s government. Indeed, some members of the UN mission were accused of colluding with forces seeking to weaken Lumumba.

In September 1960, at the height of the political crisis, Lumumba was overthrown in a military coup led by Mobutu Sese Seko, who enjoyed the tacit support of some Western powers. Lumumba was placed under house arrest but managed to escape in a desperate attempt to reach his supporters in the east of the country.

During his journey, Lumumba was recaptured in December 1960 and, along with two of his comrades, Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, handed over to the secessionist Katangan authorities. On January 17, 1961, Patrice Lumumba and his two comrades were brutally tortured by executioners. They were executed by firing squad in a heinous crime that tarnished the reputation of everyone involved. Details of the assassination were kept secret for many years, but the truth gradually began to emerge, revealing the role of Belgian and Western powers in the planning and execution of this heinous crime.

Although Patrice Lumumba’s life was cut short in his prime, his legacy lives on, inspiring subsequent generations of Africans and freedom and justice activists around the world. Lumumba has become a symbol of the struggle against neo-colonialism and foreign interference in the affairs of developing countries.

Lumumba also believed in African unity and the necessity for newly established African governments to work together to overcome similar issues and achieve progress and prosperity for their people. His vision of a free, unified, and powerful Africa inspired African liberation movements in the 1960s and 1970s.

The Belgian government formally admitted “moral responsibility” for its part in Patrice Lumumba’s killing in 2002, but this late admission did not compensate for the tragic loss sustained by the Congolese people, Congo’s ongoing instability and Africa as a whole.