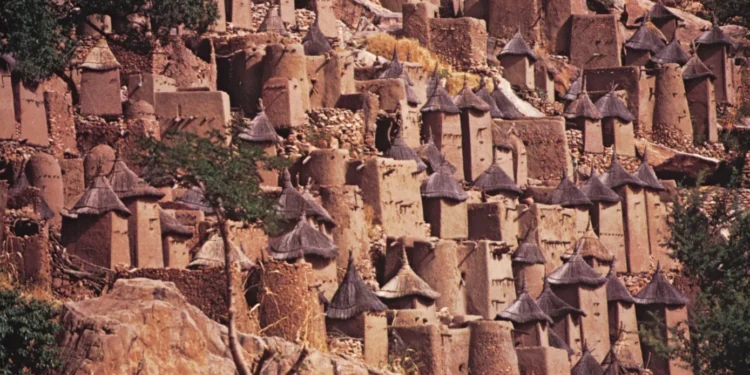

The Cliffs of Bandiagara (also known as the Bandiagara Escarpment), a sandstone chain, stretches 250 kilometers, reaching heights of up to 500 meters in some places. These cliffs form a unique natural barrier, like a mythical wall separating two worlds: the arid plains of Mali on one side and a life built on the rocky edges on the other.

Located in the Mopti region (bordered to the north by Timbuktu, to the southwest by Ségou, and to the southeast by Burkina Faso), the cliffs are surrounded by a cluster of hanging villages that appear to defy gravity, a unique architectural masterpiece carved into the rock.

According to UNESCO, “The Cliff of Bandiagara, Land of the Dogons, is a vast cultural landscape covering 400,000 ha and includes 289 villages scattered between the three natural regions: sandstone plateau, escarpment, plains (more than two-thirds of the listed perimeter are covered by plateau and cliffs).”

The region is distinguished by its environmental diversity despite its harsh landscape. Small palm groves and narrow agricultural lands appear among the rocks, testament to human adaptation to the harshest terrain. There is near agreement between oral histories and ancient traditions that the Cliffs of Bandiagara was not the original homeland of the Dogon people.

Before the Dogon arrived, the Tellem and Toloy ethnic groups inhabited the area. Its current inhabitants, the Dogon, came from the Niger or even further afield, fleeing the persecution of invaders or the advancing Islamic jihads southward. They found the cliffs a safe haven, with their height and rocky terrain in which they carved their homes.

Mark Milligan, in his article, pointed out that “Among the Dogon, several oral traditions record their origins with one relating to their coming from Mande in the Cercle of Kati in the Koulikoro Region of south-western Mali. This oral tradition believes that the Dogon first settled in the extreme southwest of the escarpment at Kani-Na where the village of Kani Bonzon is located.”

Many forces attempted to invade the Cliffs over the centuries, but the Dogon remained faithful to their isolation until the arrival of French colonialism in the early twentieth century. French colonialism attempted to subjugate them administratively and culturally but failed to penetrate their environment. The Dogon people, inhabitants of the escarpment, are considered builders of civilization, inheritors of myth, and guardians of memory due to their isolated lifestyle and the depth of their beliefs and traditions, which intertwine symbolism with religion, ritual with society, and life with death.

There are over 200 Dogon villages spread throughout the escarpment, each with a democratically chosen headman (Hogon) who also serves as their spiritual leader. They produce and hunt sometimes, and many Dogon still embrace an indigenous polytheistic African religion. Masked dances and masquerades during funerals are well-known traditions in their culture.

Researchers have revealed that traditional Dogon religion is extremely complex, based on creation myths that speak of spirits, the universe, and the cosmic order. At the heart of this religion is the concept of Amma, the supreme creator who created everything according to a precise cosmic order. They believe in the existence of spirits who govern the affairs of the world and in celestial beings such as the Nommu, who were sent to Earth to rectify cosmic imbalances.

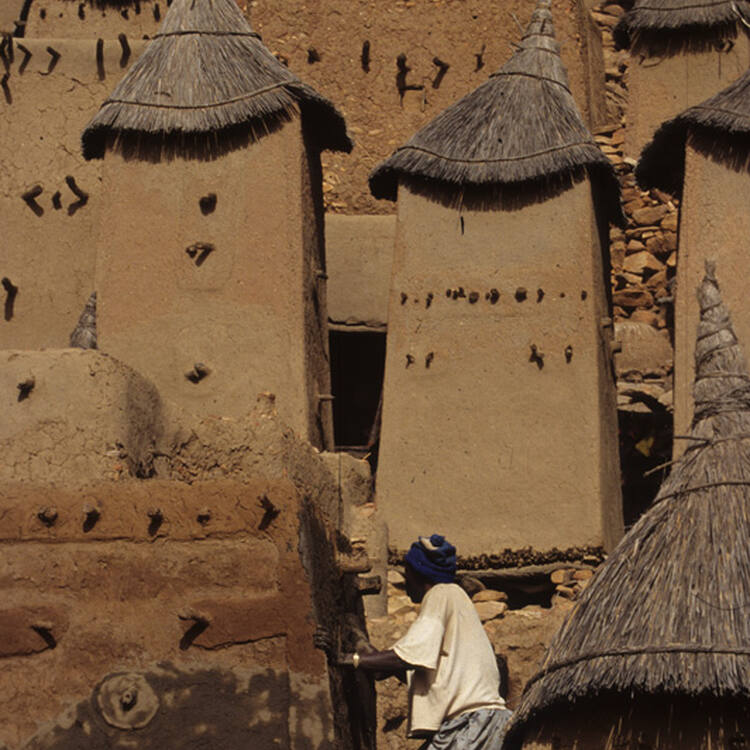

Attractive to a visit to the Bandiagara escarpment are the houses, hermitages, and tombs perched on the escarpment, revealing a meticulous architectural plan that carries spiritual and functional significance. Traditional houses are built of dried mud and covered with thatched roofs. They are often small and low to protect against the wind and sun and to maintain privacy and tranquility. The granaries have a special design, built on short poles to protect them from rodents, and are used for grain storage. There are separate granaries for men and women, symbolizing an individual’s role within Dogon society.

The dead are buried in recesses within the cliffs, an extension of the Dogon belief in the ascension of the soul. They believed that high places aided the soul’s ascent to heaven, so tombs were carved into rough terrain, like steps leading to the afterlife.

The Cliffs of Bandiagara was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1989. The World Monuments Fund (WMF) added it to its World Monuments Watch list in 2004 to highlight the problem of uncontrolled tourist visits. In 2005, the WMF awarded a grant from American Express to the Bandiagara Cultural Mission to develop a management plan.

Today, the Cliffs of Bandiagara face numerous threats, such as climate change, which weakens the stability of the rocks and impacts the fragile agriculture on which the population depends. Tourism, a relative source of income in recent decades, has declined sharply due to political instability and the rise of armed groups in the Sahel region. This is in addition to the threat of extremist organizations targeting culturally distinct areas and imposing a religious pattern that does not recognize multiple identities. The violence has forced many Dogon villagers to flee.